Denounced by the Pope for ‘erotic vagrancy’, Burton and Taylor’s scandal-soaked affair was even more epic than Cleopatra… The movie that nearly BROKE Hollywood

They called it ‘le scandale’ — the sex-fuelled, alcohol-drenched illicit love affair that blew the Hollywood star machine to smithereens, all but destroying one of its biggest film studios.

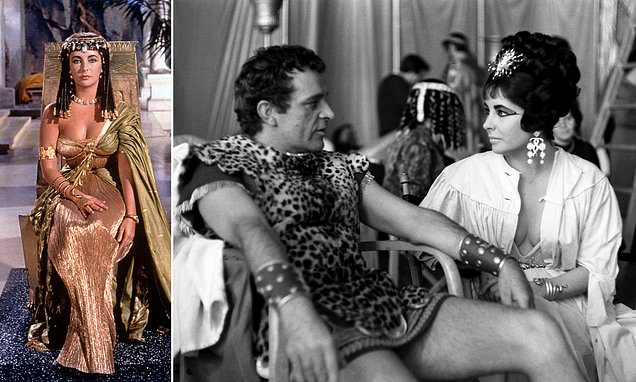

When the epic Cleopatra premiered in New York 60 years ago, it was the most expensive movie ever made.

Its star, Elizabeth Taylor, was the first woman to command a $1 million fee (about £8 million today). But it was her all-consuming passion for co-star Richard Burton that threatened to torpedo the entire production.

And the ignition of that passion can be dated to a specific day: January 22, 1962. That was the first encounter between Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, and the Roman general Mark Antony.

It was not the first time Taylor and Burton had met. In fact, they had been introduced at a party to celebrate the premiere of another ancient epic, The Robe, in 1953. Burton, who played a Roman tribune and Christian convert in that film, remembered: ‘She was so extraordinarily beautiful that I nearly laughed out loud.’

When the epic Cleopatra premiered in New York 60 years ago, it was the most expensive movie ever made. Pictured: Elizabeth Taylor playing Celopatra in the 1963 film

Taylor, a former teen star who had recently married her second husband, said: ‘My first impression of Richard was that he was rather full of himself.’

If that encounter in 1953 was inconclusive, their first scene on camera together was seismic. Both stars were staggered by the instant sexual attraction. Within two or three days, they had plunged into an affair — and although both were married to other people, they took little trouble to hide it.

‘There was never any point at which Richard and I began,’ Taylor wrote three years later. ‘We just loved each other, and there was no discussion of it. I mean, it was there — a fact of our lives. Richard and I really fought and hurt each other tremendously to keep it from happening. My God, we told each other to leave a hundred times.

‘I was, I suppose, behaving wrongly because I broke conventions. But I didn’t feel immoral then, though I knew what I was doing — loving Richard — was wrong. I never felt dirty because it never was dirty.

‘I felt terrible heartache because so many innocent people were involved. But I couldn’t help loving Richard — it was a fact I could not evade.’

Some on the set thought little of it. Actress Jean Marsh, who played Octavia and went on to star in Upstairs Downstairs, said: ‘The film was so extravagant, so louche, it affected everyone’s lives. It was a hotbed of romance — Richard and Elizabeth weren’t the only people who had an affair.’

They were, however, by far the most famous. Liz was already on her fourth marriage, to crooner Eddie Fisher. That match outraged many in America because she ‘stole’ Eddie from his previous wife, actress and national sweetheart Debbie Reynolds.

Elizabeth Taylor playing Cleopatra, and Richard Burton playing Mark Anthony in the 1963 film

Taylor frequently received hate mail, death threats and voodoo dolls with pins stuck in them. When she arrived to witness Fisher begin his residency at Tropicana in Los Angeles, just prior to their wedding in 1959, she was greeted by pickets waving ‘Liz Go Home’ and ‘Liz Leave Town’ signs.

Burton had been married since 1949 to Sybil Williams, a former actress and the mother of their two children, Kate and Jessica.

At first Sybil refused to believe the threat to her marriage was serious: she was accustomed to rumours of affairs. ‘It is best for Rich to be free to work out his own future,’ she said philosophically.

But when Eddie Fisher (or ‘Mr Elizabeth Taylor’, as the Press called him) flew to Rome on a mission to win back his wife, Sybil realised this was no mere fling. Without warning her husband, she took their daughters and flew to New York.

‘Richard is mine,’ she announced to journalists. ‘He will always be mine. I will never give him up to Elizabeth Taylor or to any woman.’ Burton was amused and baffled by all the attention, and certain that he could salvage his marriage to Sybil.

Early in 1962, he took a break from the interminable filming of Cleopatra and flew to Paris, for a two-day cameo in the D-Day epic The Longest Day.

From there he planned to fly to New York, to placate his wife and see his daughters.

But shocking news broke while he was away of a suspected suicide attempt by Taylor. Burton rushed back to Rome, fighting his way through a horde of 40 photographers at the airport.

Elizabeth Taylor, was the first woman to command a $1 million fee (about £8 million today). But it was her all-consuming passion for co-star Richard Burton that threatened to torpedo the entire production

In fact, there had been no suicide bid. Suffering from a bout of food poisoning, days before her 30th birthday, Taylor took sleeping pills. When her hairdresser arrived the next morning, she found the star unconscious and saw an empty pill bottle — and leapt to the wrong conclusion.

Taylor was rushed to Rome’s Salvator Mundi hospital, where doctors discovered there was nothing wrong with her.

Incensed by the furore, Burton issued a statement, lashing out at ‘uncontrolled rumours . . . distorted out of proportion’ that were ‘damaging to Elizabeth’.

This was all the confirmation the public needed. The overdose might not have been real but the affair clearly was. Picture editors on newspapers around the world were desperate for shots of the couple together, and offered serious sums to extras for photographs snatched on set.

One actress hid a camera in her beehive hairdo, while another concealed one that was attached to her bra and operated by manipulating her left breast ‘like a bell push’.

With her marriage to Fisher effectively over, Taylor decided to wrest Burton away from Sybil.

‘They want pictures,’ she told him. ‘So let’s give them more pictures than they could ever want. Let’s give them so many pictures, they’ll never want to point a camera at us again.’

The Pope bewailed Taylor’s divorces: ‘Three husbands buried, with no other motive than a greater love that killed the one before’

Burton agreed — and, the next day, was staggered to see photos of the two of them, openly affectionate and revelling in each other’s company around Rome, on every front page.

‘I had no idea she was so f****** famous!’ he chortled to a friend.

The Los Angeles Times trumpeted: ‘Probably no news event in modern times has affected so many people personally. Nuclear testing, disarmament, Berlin, Vietnam and the struggle between Russia and China are nothing comparable to the Elizabeth Taylor story.’

Many condemned their affair, though none more stridently than the Pope.

The Vatican issued a bulletin, aimed at Taylor without naming her. It denounced ‘the caprices of adult children’ and their ‘erotic vagrancy’ which offended ‘the nobility of the heart, which millions of married couples judge to be a beautiful and holy thing’.

The Pope bewailed Taylor’s divorces: ‘Three husbands buried, with no other motive than a greater love that killed the one before.’

From its beginning, when the movie was no more than a draft script, Cleopatra was accused of promoting immorality. Hollywood’s watchdog, the Motion Picture Association (MPA), warned that the story should not be filmed if it appeared to condone the Egyptian Queen’s affairs with both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

‘There should be no scenes showing Cleopatra nude while she is bathing,’ insisted the MPA. ‘There should be no open-mouth kisses. Lucius should not conduct himself in a way that would characterise him as a fairy.’

The track record of producer Walter Wanger reassured no one. A Hollywood veteran who had worked with everyone from Greta Garbo to Laurel and Hardy, he hit the headlines himself in 1951 when he became convinced that his wife, the actress Joan Bennett, was having an affair. After hiring a private detective, he confronted her lover, the agent Jennings Lang, and shot him in the groin.

Wanger was charged with assault with a deadly weapon. He pleaded temporary insanity, called studio boss Samuel Goldwyn as his character witness during the trial, and was sentenced to four months in jail.

But he was trusted by Twentieth Century Fox to oversee the production of Cleopatra, which in 1958 was originally conceived as a vehicle for the studio’s rising star, Joan Collins. The idea came from the head of Fox, Spyros Skouras, but it came at a price.

‘Both the head of the studio and the CEO of the studio promised Cleopatra to me if I would be “nice” to them,’ Collins later said, ‘and I wouldn’t be nice to them. I know I would have gotten it, if I had gone along with Skouras’s advances.’

When she proved unamenable, the bosses looked for reasons to drop her from the picture. Skouras made snide remarks about her figure, complaining that she had ‘eyes bigger than boobs’.

Wanger raised doubts about her deportment, noting: ‘Hermes Pan [Fred Astaire’s choreographer] is working with Joan, trying to improve her posture and walk so she will have the grace and dignity of Cleopatra.’

Other actresses were suggested, including Jean Simmons, Joanne Woodward, Claire Bloom, Cyd Charisse, Lee Remick and Kim Novak. Audrey Hepburn was said to be interested but her studio, Paramount, refused to lend her to Fox. Jeanne Moreau was dismissed because of her French accent. Susan Hayward was considered, at 41, to be too old.

Eventually, the part was offered to Liz Taylor: ‘I was in my bath when my lawyer called and asked me what I wanted to do about the “Cleopatra thing”. I thought I would dispose of it by asking something impossible. “Tell him I’ll do it for a million against 10 per cent of the gross”.’

Marilyn Monroe received only half a million for Some Like It Hot, in 1959. But Taylor signed her seven-figure contract that October. Marlon Brando and William Holden were the only actors who had ever received such a fee.

But she brought immediate and unexpected problems in her wake. Although she was raised in a Christian Scientist family, Taylor had converted to Judaism after the death of her third husband Mike Todd, who was killed in a plane crash in 1958.

She and Eddie Fisher were married in a Jewish ceremony at a Las Vegas temple, and her Hebrew name was Elisheba Rachel.

Her religion made it impossible for Cleopatra to be filmed, as originally planned, in Egypt. President Nasser’s Egyptian government had offered to supply 10,000 of its soldiers for the battle scenes, and Skouras had reciprocated with a pledge of five further films to be made by Fox in Egypt — including one, at Nasser’s insistence, starring Gina Lollobrigida.

But the deal was scuppered by a throwaway comment by Taylor in a magazine interview: ‘It will be fun to be the first Jewish Queen of Egypt.’

Today, Cleopatra is remembered as the beginning of cinema’s most tempestuous love story, but also as the end of the system by which movie moguls were dictators exercising ruthless control over actors and their careers. Taylor and Burton were beyond anybody’s control.

The scale of extravagance during the three-year shoot was mind-boggling. Even before Burton entered the picture, months of failed production at Pinewood studios were bedevilled by union battles and foul weather.

One extra recalled: ‘I always remember Liz Taylor turning up on set in a white Rolls-Royce Phantom, wearing a fur coat. She’d get out of the car, decide it was too chilly and go straight back to the hotel.’

The persistent rain and cold gave Taylor a chill, which turned to fever and then pneumonia. She collapsed at her suite in the Dorchester hotel and was revived by a doctor and a respiratory specialist before being admitted to a private clinic. There she underwent a tracheotomy, with a two-inch incision into her throat for a breathing tube.

One news agency reported that she had died — but within a week she was sitting up in bed, able to drink champagne with friends.

She described her near-death experience to the American author Truman Capote: ‘It was like riding on a rough ocean, then slipping over the edge of the horizon with the roar of the ocean in my head, which I suppose was really the noise of my trying to breathe.’

Meanwhile, the rain continued. When actors spoke, vapour from their mouths formed clouds in the air, though this was supposed to be North Africa. The palm trees took such a battering from the blustery wind that fresh fronds had to be flown in from Egypt every day. The replica of Alexandria harbour, which held a million gallons of water, was in danger of overflowing.

By the time the English set was abandoned, just eight minutes of usable footage had been filmed, at a cost of $6.45 million (£58 million today). This disaster committed producer Walter Wanger and Twentieth Century Fox to complete the movie, however prohibitive the cost. It was too big to fail.

The Pinewood sets were not entirely wasted: producer Peter Rogers borrowed them for Carry On Cleo. Its leading lady, Amanda Barrie, even wore jewelled shoes that had been made for Liz Taylor.

Filming on the real Cleopatra moved to Rome, where Taylor was accompanied by personal secretaries, doctors, cooks, hairdressers, a maitre d’ and 156 suitcases, with food flown in from her favourite deli in New York.

By 1963, Taylor wished she had never taken the role. With Fox threatening to sue her and Burton for dragging the production into disrepute with their affair, she contemplated quitting. But, she told a friend: ‘If I walk, I’ll never work again and Twentieth Century Fox will crumble. Cleopatra is three-quarters done and it’s too late for them to replace me. If I walk out of here, Fox is as good as dead.’

Writs were already flying. Circus owner Ennio Togni, supplying the animals for Cleopatra’s grand entry to Rome, was originally commissioned to provide 100 elephants. This was reduced to ten, and then to four. When he received a memo informing him that ‘the elephants were unfit for film work’, Togni protested that his menagerie was being ‘slandered’, and sued.

The first complete version of the movie came in at five hours and 20 minutes. Studio boss Darryl Zanuck ordered cuts and, at the premiere on June 12, 1963, Cleopatra ran for four hours and three minutes. An intermission at the halfway mark was added, to mollify cinema managers by enabling them to sell sweets and ice-creams in the interval.

But early reports from New York showed that the punters were unhappy, with up to 200 a day denouncing the epic as ‘boring’ and demanding a refund. More swingeing cuts reduced the film to three hours and 12 minutes.

Reviews were lacklustre, but they didn’t hurt the box-office takings. In the second half of 1963, the film took $57 million in ticket sales — just about breaking even.

Different edits were screened around the world: in the Philippines, censors cut six scenes, including Taylor’s nude bath. In General Franco’s Spain, half an hour was chopped out, including any shots that showed Taylor’s cleavage.

After almost buckling under the costs of it all, Fox studios were saved two years later by The Sound Of Music, a musical that cost a more modest $8 million to make (£77 million today) and became the biggest box-office smash in history.

Taylor and Burton were married in Montreal in March 1964, and starred together again in films including The VIPs, then The Sandpiper and The Taming Of The Shrew. They divorced in 1974, remarried the following year and were divorced for the second and last time in 1976. Burton died in 1984, Taylor in 2011.

The couple did not remember Cleopatra fondly and did not watch it for years, until their children insisted. Afterwards, Liz delivered her verdict: ‘You know, it’s really not that bad after all.’

- Adapted from Cleopatra And The Undoing of Hollywood: How One Film Almost Sunk the Studios, by Patrick Humphries, to be published by The History Press on May 25 at £20. © Patrick Humphries 2023. To order a copy for £18 (offer valid to 27/05/23; UK P&P free on orders over £25), visit www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

Source: Read Full Article