US Steptoes? Stranger things have happened: PATRICK MARMION reviews Mad House

Mad House (Ambassadors, London)

Rating:

Verdict: Crazy for Harbour and Pullman

The Fellowship (Hampstead, London)

Rating:

Verdict: Sister thwacked

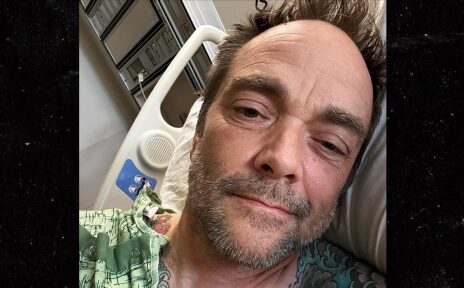

Few actors can fill a stage like David Harbour, who is making his West End debut at the Ambassadors Theatre — and not just because he’s a 6 ft 3 in grizzly bear of a man.

Like a grizzly, the star of Netflix smash hit Stranger Things (and husband of pop star Lily Allen, who made her own West End debut last year in 2:22 A Ghost Story) may look deceptively warm and cuddly. But in front of an audience he can be dangerous and unpredictable, too.

What a combo he makes, therefore, with the no less mesmerising Hollywood actor Bill Pullman (Independence Day, While You Were Sleeping) in Theresa Rebeck’s new play Mad House. It’s the story of seriously dysfunctional siblings convening in Pennsylvania for the death of their wicked and manipulative father (Pullman).

What a combo he makes, therefore, with the no less mesmerising Hollywood actor Bill Pullman (Independence Day, While You Were Sleeping) in Theresa Rebeck’s new play Mad House

Harbour plays the son, Michael, who’s caring for his terminally ill father while also recovering from a nervous breakdown that coincided with the death of his mother.

He and Pullman are like an American Steptoe and Son, bound together in the hell of a tumbledown clapboard house with peeling paint, filled with tatty family relics.

Wearing sneakers, pyjama-bottoms and a washed-out T-shirt, melancholy Michael is an idealistic former oil company executive who taught himself to be docile, in order to get himself discharged from the state psychiatric facility. But that doesn’t stop his wheedling father trying to push him back over the edge.

Michael is a gentle giant, but he’s also lethally sarcastic. He can just about hold it together with his vexatious dad, but can’t help blowing his top at his glib banker brother, or his controlling lawyer sister, who rocks up to take over.

David Harbour plays the son, Michael, who’s caring for his terminally ill father while also recovering from a nervous breakdown that coincided with the death of his mother

He’s a glorious showman, too; impulsively drinking from a garden spray bottle and wearing a coat the wrong way round, like a DIY straitjacket.

Pullman’s sly and twisted father — with his snake eyes and provocative eyebrows — takes indecent pleasure in watching his boy writhe in mental agonies. Nor does he have any intention of going gently into his grave and, lugging an oxygen tank about the stage, demands cigarettes, booze and hookers.

Rebeck’s gloriously off-the-wall drama has soul in spades, and feeds her leading men with one-liners to relish. But in the supporting roles, her characterisation is patchy; and her muddled ending leaves us hanging.

Wealthy little brother Nedward (Stephen Wight) is written as little more than a sheepish yuppie. And sister Pam’s (Sinead Matthews) motivation for wanting Michael re-interred in the psychiatric hospital is under-explored. At least the nurse, Lillian (Akiya Henry), brings a touch of sanity — and some pain of her own.

Best seat in the house

The end of the night

Ben Brown’s drama about the meeting of the Nazi architect of the final solution, Heinrich Himmler, and a representative of the World Jewish Congress, Norbert Masur, stars Richard Clothier and Ben Caplan.

(From Monday , £18+, originaltheatre online.com)

But any lack of depth in Moritz von Stuelpnagel’s murky production won’t bother too many Harbour or Pullman fans. Here, they are a pair of theatrical pyrotechnicians who set Rebeck’s sometimes creaky play alight.

Another family drama, The Fellowship by Roy Williams, was blighted by losing its leading actor, Lucy Vandi, to ill-health a few days before it was due to open last week.

Cherrelle Skeete, who had been playing two minor roles, bravely stepped in, and is easily the best thing in a ropey drama about inter-generational conflict in a black British family. Her character, Dawn, is a single mum whose eldest son was murdered in a racist attack, while her younger boy has taken up with one of the white girls she believes was part of the gang responsible.

Her barrister sister, meanwhile, has foolishly taken points on her driving licence for her white married MP lover.

And their mother, who came to the UK on the Windrush, is upstairs dying — but is almost completely ignored until she falls down dead with a bump upstairs.

Williams used to write compelling dramas driven by sharp moral dilemmas; plays like Sing Yer Heart Out For The Lads. Here we have only stereotypes, stuck in cliched situations and arguing in soundbites.

Blazing in Jamaican patois when she’s vexed and RP when she’s not, only Skeete stands out by letting rip with a character divided between her sectarian black politics and her all-white playlists on Alexa.

Paulette Randall’s astonishingly vague, two-hour-and-40-minute production lacks any sense of place; and sets the action inside what appears to be an Alexa console with spinning light disc above and below the stage.

Perhaps that corresponds to the play’s pop-psychology, but it does little to involve the audience in the two-dimensional saga.

King Lear conquers Covid to rule the Globe

King Lear (Shakespeare’s Globe, London)

Rating:

Verdict: Hits the sweet spot

Despite its star, Kathryn Hunter, just coming back from a Covid break in the title role, and the director, Helena Kaut-Howson, having been injured in a car accident two weeks before opening night — oh, and a cast member missing at this week’s matinee — this is a production of Shakespeare’s tragedy that the Gods of Theatre have been unable to prevent. And let us give thanks for that!

The show must — and has — gone on, with Hunter’s tiny, wizened Lear commanding a good deal of affection as the elderly monarch who divides his kingdom between his sycophantic daughters Goneril and Regan, while banishing the one he really loves: Cordelia.

Sometimes railing in a wheelchair, Hunter has the look of Davros from Doctor Who, only frailer and more vulnerable. She also has the physique of an autumn leaf and her delicate sense of Lear’s pathos is nearly blown away in the famous storm scenes.

And yet, as she descends into madness, she holds the stage with squawking eccentricity and pleading with invisible gods, rather than portentous rage or bombast.

Despite its star, Kathryn Hunter, just coming back from a Covid break in the title role, and the director, Helena Kaut-Howson, having been injured in a car accident two weeks before opening night — oh, and a cast member missing at this week’s matinee — this is a production of Shakespeare’s tragedy that the Gods of Theatre have been unable to prevent

The big pay-off is in the ending — which can leave the audience more exhausted than moved. Here, though, the restless open-air playhouse is rapt with silence.

One measure of Hunter’s success is the tenderness of her relationship with her court Fool (played by the Globe’s always terrific boss Michelle Terry). The Fool’s arcane Elizabethan gags usually cruise thousands of feet over the heads of the audience, but with Terry also playing Cordelia, she and Hunter find an intimacy that proves the beating heart of the play.

Kaut-Howson’s absence as a director can mean the drama lacks momentum, and the cast could perhaps dial up the heat on Lear. They sometimes seem fearful of breaking her, like a Ming vase.

Still, Ryan Donaldson makes a long-haired, Northern Irish, thinking woman’s crumpet of an Edmund, the interloping opportunist. Ann Ogbomo is nicely impatient as the wicked sister Goneril, while Marianne Oldham is craftier and more flirtatious as her sibling Regan.

It’s not a landmark production, but it is a sound and unusually sweet account of a seriously demanding drama.

Evelyn (Southwark Playhouse)

Rating:

Verdict: Thriller goes adrift

‘Oh I do like to be beside the seaside! I do like to be beside the sea,’ sings a joyless accordionist, masked in executioner style rather than for Covid protection. The unsettling tone continues with a poor Punch and Judy show in which Punch brutalises Judy and murders a baby.

Along the beach, a boho older woman (Rula Lenska, sparkling in costume jewellery and eye-shadow) welcomes a forlorn stranger in a faded Mickey Mouse top to her sheltered accommodation which, against the rules, she is letting on Airbnb.

You don’t have to be Sherlock to know that no one here is quite who they seem.

Somewhere in Tom Ratcliffe’s Evelyn drifts a promising, potentially theatrical play about secrets and lies, the power of mob justice, abuse and exploitation which Madelaine Moore’s messy staging fails to anchor.

We are in the sleepy town of Walton-on-the-Naze, on the Essex coast. Lenska shines as lonely Jeanne, simultaneously moving and maddening. She has dementia, but misnaming her nurse as Linda (she is Laura) seems purposeful carelessness rather than confusion, while not taking her meds and boasting that she plays bridge, not bingo, is surely deliberate.

There’s a nice moment when her mousey guest, Sandra, whom she introduces as her god-daughter, says ‘Trust me, you don’t want to give that woman a microphone’, with some in the audience remembering Lenska’s Rock Follies.

Nicola Harrison almost cracks the harder role as faltering, charmless Sandra, all evasion, unease, inconsistencies and lies. So when news breaks that the girlfriend of a murderer has been given a new identity and gone to live by the seaside, Laura (splendidly tough and totally plausible Yvette Boakye) gets suspicious.

Her concerns become hysterical when her daughter disappears and her electrician brother, Kevin (Offue Okegbe) and Sandra have suddenly become a couple. The play collapses.

Given sharper writing and a tighter focus, Evelyn could have a future.

Georgina Brown

Source: Read Full Article