In a recent online presentation, editors and researchers working on a first-of-its-kind dictionary of African American English gave a status update on the project. As academics explained their various methodologies, slides displayed behind them showed words that are more often associated with Twitter than Oxford: “Bussin,” virtual attendees were told, means impressive or tasty, while a “boo” is a lover.

Those were two of the first 100 words that the Oxford University Press said it had prepared to include in the Oxford Dictionary of African American English, the hopeful result of the three-year research project announced last spring.

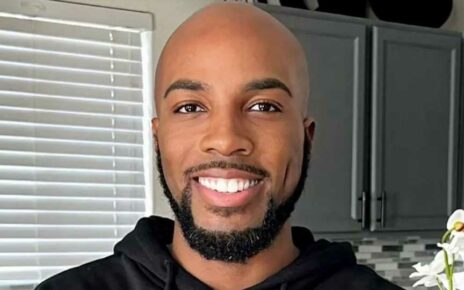

The researchers say they aim to publish a first batch of 1,000 definitions — some words and phrases will have more than one — by March 2025. But the more important goal of the project, which will be edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr., a scholar of African American history at Harvard University, is to underscore the significance of African American English and to create a resource for future research into Black speech, history and culture. Among his other bona fides, Professor Gates is something of a dictionary nerd.

“When I was in the third grade, we studied the dictionary,” he said in a recent interview. “We had a unit on how to use the Webster’s dictionary, and even then — third grade, that means I was 8 years old — I thought the dictionary was magical.”

Professor Gates now collects and cherishes rare and historical dictionaries, including one he bought in the early days of the pandemic, when the future did not seem as sturdy as it once was.

“I was sitting here in this kitchen, sheltering in, doing a Zoom,” he recalled. “I said: ‘You know what? We could die at any time. I’m going to buy a first edition of the Samuel Johnson dictionary.’”

To support their etymological claims, researchers and editors from Oxford Languages and the Harvard University Hutchins Center for African & African American Research have drawn on lyrics from jazz, hip-hop, blues and R&B as well as letters, diaries, newspaper and magazine articles, Black Twitter, slave narratives and abolitionist writings. Individual entries will be explained using quotations pulled from Black literature, including examples from Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison and Martin Luther King Jr.

One of the main challenges for the researchers is finding Black sources to confirm the use of the words.

“The further back in history, the less we can find Black people having agency over how we’re written about,” said Bianca Jenkins, a lexicographer working on the project. “Due to enslavement, Black people were prevented by law from being educated, from being taught to read. Black people had to really take it upon ourselves and educate ourselves.”

But it is not simply about the words that appear in letters, books, poems and lyrics. It is also about the words that morphed into other pronunciations and evolved to have a veiled meaning, for the safety of Black people.

Black people take language and “wrap it around themselves,” Professor Gates said in an interview. “They turn words inside out.”

“We are endlessly inventive with language, and we had to be,” he continued. “We had to develop what literary scholars call double-voiced discourse. We had to learn to speak the master’s language, then you had to learn to speak under the masters so that you could have a coded way of speaking English that would allow you to voice your feelings without being killed, whipped or — worst-case scenario — without being lynched.”

The dictionary will exist as a living record well after March 2025 has come and gone: According to Professor Gates, the public will continue to be able to suggest entries for consideration even after the first edition is published. Professor Gates recalled asking his cousin, who fought in the Vietnam War, to add a few words. He submitted 200, Professor Gates said, his wide smile revealing the apples of his cheeks.

In April, Oxford Languages and the Hutchins Center shared 10 entries with The New York Times. Below are selected definitions, variant forms and etymologies.

bussin (adjective and participle): 1. Especially describing food: tasty, delicious. Also more generally: impressive, excellent. 2. Describing a party, event, etc.: busy, crowded, lively. (Variant forms: bussing, bussin’.)

grill (noun): A removable or permanent dental overlay, typically made of silver, gold or another metal and often inset with gemstones, which is worn as jewelry.

Promised Land (n.): A place perceived to be where enslaved people and, later, African Americans more generally, can find refuge and live in freedom. (Etymology: A reference to the biblical story of Jewish people seeking freedom from Egyptian bondage.)

chitterlings (n. plural): A dish made from pig intestines that are typically boiled, fried or stuffed with other ingredients. Occasionally also pig intestines as an ingredient. (Variant forms: chitlins, chittlins, chitlings, chitterlins.)

kitchen (n.): The hair at the nape of the neck, which is typically shorter, kinkier and considered more difficult to style.

cakewalk (n.): 1. A contest in which Black people would perform a stylized walk in pairs, typically judged by a plantation owner. The winner would receive some type of cake. 2. Something that is considered easily done, as in This job is a cakewalk.

old school (adj.): Characteristic of early hip-hop or rap music that emerged in New York City between the late 1970s to the mid 1980s, which often includes the use of couplets, funk and disco samples, and playful lyrics. Also used to describe the music and artists of that style and time period. (Variant form: old skool.)

pat (verb): 1. transitive. To tap (the foot) in rhythm with music, sometimes as an indication of participation in religious worship. 2. intransitive. Usually of a person’s foot: to tap in rhythm with music, sometimes to demonstrate participation in religious worship.

Aunt Hagar’s children (n.): A reference to Black people collectively. (Etymology: Probably a reference to Hagar in the Bible, who, with her son, Ishmael, was cast out by Sarah and Abraham [Ishmael’s father], and became, among some Black communities, the symbolic mother of all Africans and African Americans and of Black womanhood.)

ring shout (n.): A spiritual ritual involving a dance where participants follow one another in a ring shape, shuffling their feet and clapping their hands to accompany chanting and singing. The dancing and chanting gradually intensify and often conclude with participants exhibiting a state of spiritual ecstasy.

In addition to appearing in a physical edition of the Oxford Dictionary of African American English, the entries will also be added to the wider word bank of the Oxford English Dictionary, Professor Gates said.

“That is the best of both worlds, because we want to show how Black English is part of the larger of Englishes, as they say, spoken around the world,” he said.

More than just a collection of words, Professor Gates said, the new dictionary will serve as a record of the ways Black people have molded the English language to protect themselves and also keep a morsel of autonomy in a world that would have them have none.

“Everybody has an urgent need for self-expression,” he said, adding, “You need to be able to communicate what you feel and what you think to other people in your speech community.

“That is why we refashioned the English language.”

Source: Read Full Article