Academy Award nominee Agnieszka Holland follows the harrowing ordeal of a refugee family trapped on the margins of the E.U. in “Green Border,” a gripping drama from the prolific Polish director that plays in competition at the Venice Film Festival.

The film is set in the treacherous and swampy forests that make up the so-called “green border” between Belarus and Poland and focuses on the humanitarian catastrophe that unfolded when Belarus’ president, Alexander Lukashenko, opened the country’s doors to migrants in a cynical political gambit to flood the E.U. with refugees.

Told in chapters from alternating points of view, it tells the story of a family of Syrian refugees, an English teacher from Afghanistan, a young Polish border guard and a group of activists whose lives collide in the border zone, a bleak no-man’s land where Polish and Belarusian guards operate with brutal impunity.

The screenplay — written by Holland, Gabriela Łazarkiewicz-Sieczko and Maciej Pisuk — is inspired by real events and based on hundreds of hours of research, including interviews with refugees, border guards, borderland residents, activists and experts on migration. The film is a co-production between Poland, France, Belgium and the Czech Republic. Films Boutique, which is handling international sales, has closed a raft of deals ahead of the movie’s Venice premiere.

Like many of Holland’s films, “Green Border” is a cri de coeur of unmistakable urgency — an attempt, she says, “to give the voice to those who are voiceless.” The empathetic range of her film includes not only refugees forced to flee their homelands, only to be trapped in limbo in Europe, but activists who are “criminalized and blamed by the state” and even the border guards themselves — some of whom, she insists, are ill-equipped to respond to the desperate situations they encounter.

In that regard, she says, her latest feature is of a piece with other films in her oeuvre that reflect on the choices individuals are forced to make, often when faced with “impossible dilemmas.” It is in those existential gray areas that even ordinary people prove capable of heinous acts, she says, while wrong-doers can show the capacity for good. “Where is the border, the frontier between good and evil?” she asks.

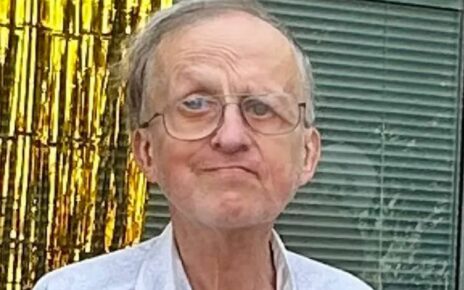

One of world cinema’s great moral consciences, Holland has returned time and again throughout her career to what she describes as “the great and tragic subjects of the 20th century” in films including the Holocaust survival drama “In Darkness” — Oscar-nominated for best foreign language film in 2011 — and “Mr. Jones,” a biopic of the young Welsh journalist who blew the first public whistle on the man-made famine of 1932-33 in Soviet Ukraine.

The director, who fled communist Poland for France in 1981 before the imposition of martial law in the Eastern European country, insists that the refugee crisis — made worse in the nearly 18 months since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — represents an existential threat to the core beliefs on which the European Union is based.

“I don’t want Europe to abandon all values that Ukrainian soldiers now are fighting for,” she says. “Human rights. The dignity of every human being. Democracy. Equality. Brotherhood. Solidarity.” She nevertheless worries that such a fate is “awaiting us. This catastrophic vision is very real if we don’t do something about it,” she says.

President of the European Film Academy since 2020, Holland describes herself as an “existential pessimist,” aware that “humanity is capable of the worst” while at the same time insisting that the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice. Progress, however painfully gained, continues to nudge humankind forward, she believes, despite “the lack of courage, the lack of imagination, the lack of collaboration” among the policymakers who shape our collective fates.

The three-time Oscar nominee acknowledges she’s no politician, to the collective relief of countless moviegoers. But she persists in using the cinematic tools at her disposal to confront — in whatever way she can — the starkest challenges our societies face. “Cinema has to be the partner to truth and…to ask important questions,” she says. “I don’t think cinema will bring the answers, but the questions are our strength.”

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article