What’s the darkest moment you’ve ever seen in a rock ‘n’ roll documentary? Up until now, I’d have said the answer was obvious: the sequence in “Gimme Shelter” where Meredith Hunter, in his lime-green suit, rushes the stage at Altamont with a gun in his hand and gets stabbed in the back, half a dozen times, by a member of the Hell’s Angels. For pure heart of darkness, what could top that? But I’ve just seen “Anita,” Svetlana Zill and Alexis Bloom’s very good documentary about Anita Pallenberg — beautiful and imperious scenester of the ’60s and ’70s, Hollywood actress and icon of scruffy-chic rock royalty, wife of Keith Richards, muse to several of the other Rolling Stones. And there’s a moment in it that made me suck in my breath in shock and horror as much as “Gimme Shelter” does.

The year is 1976. Keith and Anita have been living as a slovenly, decadent version of a domestic family unit. We’re heard their lives described, with disarming honesty, by Anita, whose words are taken from the manuscript of “Black Magic,” an autobiography she wrote but never published. (It’s read as narration by Scarlett Johansson.) Keith and Anita’s son, Marlon Leon Sundeep, is 6 years old (his two middle names carry the initials “LSD,” à la “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”). Their daughter, Dandelion Angela, is just three. Mired in drugs (acid, cocaine, heroin) and known around the world for it, to the point that it’s hard for them to find a place that will have them, Keith and Anita have moved their family dozens of times; they’re now living in Geneva. On March 6, Anita gives birth to their third child, a son named Tara Jo, and Keith goes on the road for his latest tour with the Stones.

Anita is left behind to care for the infant all by herself. She feels distraught and abandoned. She is using hard drugs. On June 6, when the baby is just 10 weeks old, he dies. It is pronounced a crib death (what would come to be called SIDS). “The Swiss doctors told me it wasn’t my fault,” writes Anita. “But if I had been more together, could I have done something?” The viewer can’t help but wonder if the answer is yes.

I haven’t gotten to the darkest part. That’s where Keith, on the day he learns the tragic news, is scheduled to play a concert with the Stones. The other band members tell him he shouldn’t; he doesn’t need to perform. But Keith insists. And we see footage of that concert. Here’s Keith, in all his hooligan brashness, cool as a cucumber onstage, churning out the guitar solo to “Honky Tonk Women.” And we can’t put this together in our heads with what just happened. Richards has explained that if he didn’t perform that night, he thought he might have shot himself. Yet his the-show-must-go-on compartmentalization still looks cruelly inexplicable. And it ties into the larger portrait of life presented by “Anita.”

If there is any cliché phrase that’s now so cloying it can make your skin crawl, it’s sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. Taken together, those words have come to symbolize something paralyzing in its banality: the youth hedonism of a certain era and — more than that — the facile way we tend to think of it. Of course, it’s not as if that ethos ever went away. (Now it’s Tinder, drugs, and nightclub EDM.) Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll has been the lifeblood of our free culture for 50 years. In its overly institutionalized way, it’s probably more unhinged now than it was then.

Nevertheless, when you say the phrase, you’re imparting a certain mythology to a certain lifestyle. You’re saying, implicitly, “Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. What’s not to like?” What’s missing from the phrase is any hint of how the holy credo of hedonism bred a culture of recklessness. I don’t mean to come off like a right-wing scold. I still believe (who doesn’t?) in the liberating power of pleasure. But the truth is that the ’60s and ’70s opened the door to all kinds of spiritual and physical destruction that we probably don’t talk about as much as we should, and “Anita,” as a documentary, is about all of that. As filmmakers, Zill and Bloom want to celebrate everything that made Anita Pallenberg a feminine force ahead of her time. And they do. But they also show you that Anita and Keith had a complex relationship that was a crazy doom spiral.

In addition to Pallenberg’s memoir, the film is built around a towering archive of home-movie footage, so that we often feel like we’re right there with Anita and Keith, seeing who they were offstage and off-camera; we experience the sweet tranquility of lives being lived. Pallenberg met the Stones in 1965, when they were giving a concert in Munich (back in the era, she says, before Mick was dancing; he was still playing the maracas). Anita soon became involved with Brian Jones, who she thought was the most beautiful of the Stones, and the most charismatic.

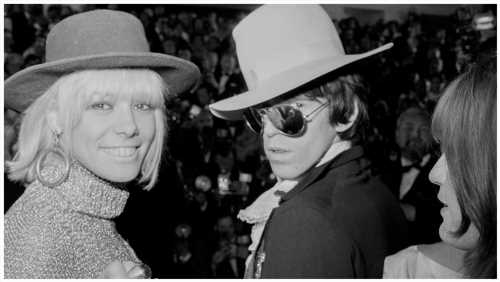

Anita herself, as we see, was a fount of charisma. She had done some modeling (which turned out to be not her thing), and she was one of those Olympian women of the ’60s who strode into a room and commanded it. With her bangs, regal cheekbones, and voracious broad smile, she looked like Nico and Carly Simon and Marilyn Chambers. “I’ve been called a witch, a slut, and a murderer,” she tells us in the narration, and though she’s referencing ways she’s been dismissed, even those testify to her power. We hear clips of Keith talking about how she was a woman not to be crossed.

She was Italian and German and spoke in a Continental accent that added to her élan. In 1963, when she was 19, she “escaped to New York,” where she found a place in the downtown art scene (“I washed Jasper Johns’ brushes”), until she linked up with the Stones. By the early ’70s, married to Keith, she’d become one of the casual inventors of post-counterculture rock style, because the clothes that Keith had become celebrated for wearing (the scarves, furs, and ambisexual shirts) were mostly hers. That’s what infused his slovenly pirate thing with such style.

Pallenberg was an actress, and a good one. We see clips of her in “Barbarella” (1968), an otherwise preposterous movie, but she played a tyrannical heavy and made her presence felt. From the ridiculous to the sublime, she co-starred in “Performance” (1970), one of the most important films of the era, and though the set was awash in drugs, that was part of what the movie was about — the new decadence as aristocratic lifestyle. She had a brief dalliance with Mick Jagger at the time but drew away from him. If you watch “Performance” now, you’ll see that Pallenberg’s own performance is excellent. But Keith didn’t want her to act — or to do anything that could add up to a career. He was that kind of possessive old-school bad-boy-as-chauvinist. She agreed to his demands and shut herself down. If she hadn’t, Pallenberg might have been a major presence in the movies of the ’70s.

She had the potential to be an artist, but it’s partly because the creative process never became front and center for her that “Anita” is such a unique rock-world documentary: a portrait of the life itself. Starting from the time they lived at Nellcôte, the rented villa in the south of France where the Stones recorded “Exile on Main St.,” and where they’d escaped to avoid paying British taxes, Anita and Keith’s lives plunged into chaos. Nellcôte was a party of hangers-on that never stopped, and once the recording sessions were over, Keith and Anita moved 20 times in 3 years; according to Marlon, he could never hold onto a set of toys. They barely furnished the homes, but for Keith everything was secondary to making music. And the drugs produced a torpor that became their normality, which Anita talks about with indelible candor. Keith, like the other Stones (well, except for Brian Jones), possessed the constitution of a “survivor.” But they left a trail of wreckage.

We hear more dark tales, culminating in the infamous 1979 incident in which Scott Cantrell, a 17-year-old part-time groundsman at Keith and Anita’s estate in South Salem, NY, killed himself with a gun at their house. He and Anita had been sexually involved, and according to Pallenberg they were watching “The Deer Hunter,” where the Russian roulette sequences inspired Cantrell to take out Keith’s gun and give the game a go. Pallenberg was never accused of legal wrongdoing, but the incident shadowed her. There followed more addiction, though now she was going into the scuzzpit of Alphabet City to score, and stealing money from friends.

Yet Anita, in her way, was a survivor too. She cleaned up and stayed sober for 14 years. (She died in 2017, at 75, due to complications from hepatitis C.) You watch “Anita” and think of what she could have accomplished had it not been for the drugs. But, of course, it’s never that simple, since the documentary captures how Pallenberg’s willingness to push everything to the edge and over it was inextricable from her cracked glamour. “Anita” is a vital portrait, but it’s the current of devastation that makes it essential.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article