Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

The Australian government will intervene in an effort to save a global deal to end plastic pollution from unravelling, as some major world economies try to water down the agreement.

Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek has flown to Paris for critical talks on the proposed global treaty, saying she is concerned that countries are trying to make the targets voluntary, instead of legally binding.

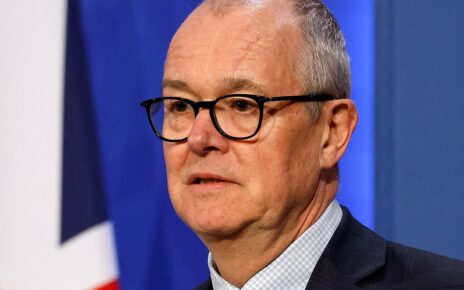

Along with Norway, Canada and France, Australia will push for “high ambition” in the pact, says Tanya Plibersek.Credit: James Brickwood

Australia last year joined the High Ambition Coalition of 20 nations including the UK, Canada, France, and Germany that aims to end plastic pollution by 2040, including a legally binding target to phase out plastic waste products by 2025.

But some countries including the United States, Saudi Arabia and China have since resisted the push for a legally binding deal, arguing nations should be able to set their own targets, similar to the Paris Agreement. These countries are among the biggest producers of plastics.

Plibersek said it was important for her to be in Paris over the weekend for the second round of negotiations after countries started to push back against making the treaty legally enforceable.

“For this to work, the treaty must be legally binding and include strong targets. Unfortunately, some countries don’t agree,” Plibersek said, without naming which countries were trying to water down the pact.

“I am aware that there are moves to sort of push back against that [legally binding targets], and so we do need to protect that.”

Plastic pollution is one of the biggest environmental threats facing the world, with at least 14 million tonnes of plastic ending up in the ocean every year and worldwide production set to double by 2040 without a major intervention.

A 2017 study found that 8.3 billion tonnes of plastics were produced since the industry began to expand after World War II, with four-fifths dumped as waste and just 9 per cent recycled.

A collection of plastic debris – dubbed the Great Pacific Garbage Patch – now occupies an area three times the size of France in the Pacific Ocean north-east of Australia.

Before flying to Paris, Plibersek said if the world doesn’t take significant action, the rate of plastics entering the ocean will triple by 2040 and outweigh fish by 2050.

She said she was also going to the Paris negotiations to give a voice to Australia’s Pacific neighbours who are more affected by the scourge of plastic waste than most other nations.

“One of the reasons I feel like I have to be there in person is a lot of pushback from some countries about reducing the use of virgin plastics [and] other countries that are saying: ‘It’s fine to have an agreement, but it shouldn’t be legally binding’,” Plibersek said.

“So I think it’s really important that Australia – along with our like-minded countries like Norway, Canada, France and others that we’ve been working very closely with – are actually there in the room to push for high ambition.”

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Credit: Ocean Cleanup Foundation

Australia now produces 2.5 million tonnes of plastic waste each year but has made significant strides recently towards a “circular economy” to eliminate plastic waste.

Last year, state and federal ministers agreed to new targets for 2025, including making packaging 100 per cent reusable, recyclable or compostable, 70 per cent of plastic packaging being recycled or composted, 50 per cent average recycled content in packaging, and phasing out unnecessary single-use plastics.

Plibersek said Australia needed to have stronger rules on packaging, which she was working on with the states and territories.

She said ordinary Australians were passionate about recycling, but the rules needed to be simpler.

“I really believe that most Australians are keen to recycle [but] sometimes get a little bit confused. They sometimes get a little bit overwhelmed when different states have different approaches, or different councils have different bins,” she said.

“They’re not sure whether this particular packaging goes in the red bin or the yellow bin, but the willingness is absolutely there.”

Plibersek said she wanted to come out of the weekend’s negotiations with the same “high ambition” that the countries backing the treaty originally envisioned.

“We are absolutely looking for a treaty that’s legally binding and that covers the whole of the plastics lifecycle, and we’re very keen to continue to work with like-minded countries to get there,” she said.

“And this second round in negotiations is also where we hoped to start really putting the meat on the bones of the treaty that would actually give effect to that stuff.”

The next meeting will be held later this year with the treaty to be agreed at the end of 2024.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article