I racked up £38,000 of debt to save my career when I had a baby: In the first part of a major series on women at work, Femail investigates the crippling toll children can take on a mother’s job prospects

When Emma Clayton decided to go back to work after five months of maternity leave, she knew there would be a price to pay.

Not just less time with her young daughter but the hefty cost of daily childcare, too.

But little did she realise just how crippling the astronomical sums involved would be. Absurdly, despite working full-time, the only way she could sustain her career and be a mother, too, was to rack up a £38,000 debt in the first eight years of her child’s life. A marketing brand manager, Emma, 47, was earning a very healthy £50,000 a year when Molly was born.

As a single mum, however, almost all of her £3,000-a-month take-home pay was swallowed up by her £1,000 mortgage repayment and childcare costs of £1,500.

‘I had five months of paid maternity leave and then looked at the sums and made a conscious decision to get into significant debt to pay for childcare so I could keep working,’ says Emma, from Witney, Oxfordshire.

‘The alternative was giving up my job and us ending up in a council house on benefits. That just wasn’t an option for me.

‘I compiled a spreadsheet and worked out how much I’d need to borrow each year in bank loans and credit cards to cover outgoings, and I committed to working even harder so that I would be in line for any bonuses and promotions.’

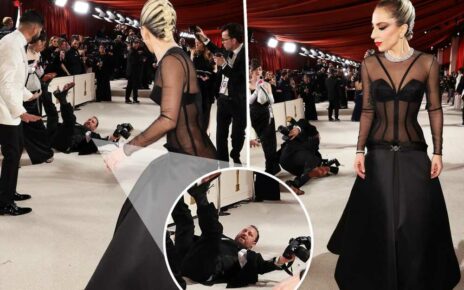

Salary swallowed up: Emma Clayton found the cost of childcare astronomical when she returned to work from maternity leave five months after her child was born

Emma and Molly’s father separated when their daughter was a few months old, and he has not been a part of her life since. The only offer of support came via the Government’s Child Support Agency (now the Child Maintenance Service) — at just £5 a week.

The financial burden rested solely on Emma’s shoulders: if she wanted to work, she was left in a bizarre quandary to which the only solution she could find was going into debt.

‘Molly was in a Montessori nursery from 8am until 6pm five days a week, and I’d keep working at weekends and in the evenings, while she was in bed,’ she says.

‘I spent many sleepless nights tormenting myself with the thought that other people were raising my daughter.

‘She even said her first word at nursery. I don’t remember what it was. It was so hard to accept this that I’ve probably blocked it out.

‘But having conversations at the end of every working day with the nursery staff, relative strangers, about all the things my daughter had done, or said, was tough.

‘However, I felt I had no choice but to accept that I missed a large chunk of her days and stay focused on my job, to keep a roof over both our heads.’

Depressingly, even with all her work and sacrifice, Emma’s career still stalled.

Once Molly started in reception class, it cost £600 a month for wraparound care before and after school, plus holiday cover. ‘I’d still feel guilty about leaving the office earlier than my colleagues to collect her,’ says Emma.

Finally, when Molly was nine, Emma quit. She now supports women who, like her, face insurmountable difficulties at work after having children.

She runs a campaign, We Mean Business, that lobbies for support for female entrepreneurs who earn, on average, 43 per cent less than their male counterparts.

Five years on, she has paid off that £38,000 debt — but still resents the fact it was her only real option at the time.

‘No one should have to get themselves into debt to be able to work and have children like I did,’ she says.

‘I see lots of women resigning, going part-time or missing out on promotions in their 30s and 40s and returning to the workplace in their 50s, by which time the gender pay gap — not to mention contributions to pension funds — is significant.’

Career struggle: Chernice Thompson, far left, with baby Frankie and Natalie Ormond. Chernice is a qualified teacher who was forced to quit her job when she had her third child due to the costs of childcare. Natalie, a social worker, had to take a career break because of the costs of childcare

With the UK the second most expensive country in Europe for childcare, after Cyprus, many women face terrible choices.

A survey by charity Pregnant Then Screwed, of women who have had an abortion in the past five years, found that 60.5 per cent said the cost of childcare had influenced that decision, while 17.4 per cent said it was the main reason they had terminated a pregnancy.

One woman told the charity: ‘I found it heartbreaking that I had to have an abortion primarily because we could not afford the cost of childcare.

‘If I had continued my pregnancy of a much-wanted child, I would have had to quit my job to care for them.

‘This would have meant we had to sell our home, as one salary would not cover the bills, which would have been detrimental to the child we already have.

‘The system is a shambles. It is so upsetting.

‘My husband and I are both professionals, yet we cannot afford to have a second child.’

A separate survey of 26,962 women, conducted this year by Pregnant Then Screwed and Mumsnet, found that 43 per cent of mothers have considered leaving their jobs because of childcare costs, while 40 per cent work fewer hours than they would like because of it.

A separate survey of 26,962 women, conducted this year by Pregnant Then Screwed and Mumsnet, found that 43 per cent of mothers have considered leaving their jobs because of childcare costs

When Natalie Ormond, an experienced social worker, went on maternity leave after having her second child six years ago, she was on track for promotion — and yet all hope of progressing evaporated once she and husband Owen sat down and did the sums.

If Natalie returned to her three-days-a-week position, childcare costs would have swallowed up all but £200 of her monthly pay.

Effectively, Natalie had no choice. She and Owen, an insolvency solicitor, agreed it made no sense for her to work for almost nothing so, when her year-long maternity leave ended, she took an extra 12-month ‘career break’ until their elder child started school.

When Natalie returned to work, in July 2018, a number of the senior roles for which she would have been eligible had come up and been filled, meaning she had missed her chance at promotion.

‘I found myself in an impossible situation. Crippling childcare costs meant I just couldn’t work for that crucial year or two, and my eight-year career, as well as my pay packet, suffered,’ she says.

‘Once women have children, all sorts of barriers suddenly appear that fathers just don’t face.

‘Many of us are not much better off than 1950s housewives, juggling parenthood and running a home which, even with a husband as hands-on as mine, still mostly falls to mothers — on top of trying to fulfil the expectations of our bosses and colleagues.’

A near-unanimous 86 per cent of providers say the subsidy is less than it costs them to provide childcare, according to the charity the Early Years Alliance. That means extra charges are passed on to parents (stock image)

All of this adds up to what Joeli Brearley, founder of Pregnant Then Screwed, calls ‘the motherhood penalty’. ‘The gender pay gap is now negligible before the age of about 30,’ she says, ‘but that’s when it really starts to widen.

‘Two-thirds of families pay the same, or more, for childcare as their rent or their mortgage, so it’s often their biggest expenditure.’

She explains that our parental leave system means it’s almost always mothers who take longer maternity leave.

‘And statistically, mothers do almost three times the childcare, housework and cooking that fathers do. So it’s no surprise that when men have children they tend to get pay rises and promotions, whereas women get demotions and pay cuts.’

Nor does the trap end once a child turns three and becomes eligible for 30 government-funded hours of childcare a week.

A near-unanimous 86 per cent of providers say the subsidy is less than it costs them to provide childcare, according to the charity the Early Years Alliance. That means extra charges are passed on to parents.

Natalie adds: ‘The role I was in before and just after my second son was born wasn’t very family-friendly because I was working in a team where we were going out to people in crisis.

‘I’d be watching the clock ticking towards 6pm knowing that my little boys would be waiting, tired and hungry, for me to pick them up, but that I also had a very responsible job which I couldn’t just walk away from.

‘And, if they were the last children to be collected, of course I felt horribly guilty.

A government-commissioned report from 2016 shows that 54,000 women a year are ‘pushed out’ of their jobs while pregnant or on maternity leave, while 77 per cent of working mothers experience discrimination at work (stock image)

‘So when it came to doing the sums and realising that we’d be barely any better off if I worked, the pull to be there for my children won out. At least I knew I’d be without the inevitable working mother’s guilt for a year.

‘That guilt was unavoidable when I went back to work and one, or both, of them would be crying or clinging to me when I dropped them off and I’d have to dash to work, with tears in my eyes.’

The pandemic provided some respite for Natalie, as both she and Owen worked from home in Leeds for much of it.

However, come September last year, Natalie could not face returning to the ‘impossible juggle’ of keeping her bosses happy while caring for her sons, Jesse and Jonah, now six and eight.

So she quit to run her own business — Smallkind, an online children’s store.

‘My position as a social worker was probably filled by a younger, childless woman who will no doubt face the exact issues I did in a few years’ time.

‘It’s just pushing the problem further down the line, effectively excluding women from certain roles and losing a lot of talent in the process,’ she says.

Institute for Fiscal Studies figures show that, by the time the average woman’s first child is 12, her hourly pay rate is 33 per cent lower than her male counterparts. So what’s the solution? (stock image)

A government-commissioned report from 2016 shows that 54,000 women a year are ‘pushed out’ of their jobs while pregnant or on maternity leave, while 77 per cent of working mothers experience discrimination at work.

Institute for Fiscal Studies figures show that, by the time the average woman’s first child is 12, her hourly pay rate is 33 per cent lower than her male counterparts. So what’s the solution?

Joeli Brearley is calling for Britain to take a similar approach to Canada, which is investing £20 billion in its childcare system over the next five years — a figure which dwarfs the £4 billion invested each year by our own government, given that Canada’s population is nearly half that of Britain.

Parents in Canada pay no more than £8.40 a day, while British parents of under-threes pay six times more, at £52.60 on average.

‘The Canadian government is not acting out of the goodness of its heart,’ says Joeli.

‘It crunched the numbers and discovered that for every dollar it invested in childcare, it got between $1.50 and $2.80 back into the wider economy.’ Emma would like to see state provision of nurseries, like schools, for all children.

A less obvious way to fight workplace discrimination is to give men better paternity leave — and so encourage them to share the burden of care more evenly throughout a child’s life.

‘In Sweden, Norway and Iceland, dads, like mums, can take up to four months’ paternity leave in the first year,’ says Joeli.

‘Fathers are [then] much more likely to take on caring responsibilities throughout childhood, reducing the likelihood of mothers being discriminated against in the workplace.’

A less obvious way to fight workplace discrimination is to give men better paternity leave — and so encourage them to share the burden of care more evenly throughout a child’s life (stock image)

Chernice Thompson, 28, is a qualified teacher who worked in a children’s home, supporting young people outside the school system, until the birth of her third child nine months ago meant she was left with little choice but to quit her job.

Working at least 37 hours a week, because her shifts varied, she was forced to pay for full-time nursery places, Monday to Friday, for her sons to ensure they would always be able to attend on the days she required childcare.

Her eldest, Noah, five, is now in reception class, but with after-school clubs for him plus nursery places for Chester, two, and Frankie, nine months, the monthly childcare bill would come to £1,400 — leaving just £300 from Chernice’s £1,700 take-home pay — from a salary of £28,000 — £200 of which would have gone on petrol.

‘The juggle between the demands of work and being a good mum was hard,’ says Chernice, from Southampton.

‘When they were ill and I had to leave work at short notice, knowing that I would be leaving my colleagues to do my work, I felt dreadful.

‘But my children are my priority and I had to be there for them when they needed me.

‘It was also painful dropping them at nursery when they were just a little under the weather, or teething, and therefore clingy.

‘There was no way it made sense to hand my children over to other people to look after five days a week, to be a measly £100 a month better off.’

Like so many mothers, she had to find new ways to bring in money and now works, self-employed, once her children are in bed — until midnight — as a social media manager.

She says: ‘My employers and, crucially, the vulnerable children I was supporting, have lost out on having someone who’s good, committed and experienced,’ she says. ‘This makes me feel sad, but I don’t feel guilty because it’s not my fault.

‘The cost of childcare and inflexible hours have created an impossible barrier to me — and far too many other women — pursuing the careers we love.’

Source: Read Full Article