By Karl Quinn

For many of us, Terminator’s apocalyptic vision of an AI-dominated world is hard to shake.

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

No one could ever accuse Alex Proyas of being a technophobe, but when he put AI through its screenwriting paces recently he was far from impressed. He started with a simple prompt in Chat GPT: Can you help me to write a screenplay for a film?

“It responded ‘of course I can’,” says the Sydney-based writer-director-producer who has been prodding at the interface of film and digital technology since his hand was forced by the death of Brandon Lee on the set of The Crow, a film written and directed by Proyas, in 1993 (the actor’s face was digitally added to a body double for some scenes, the first time that had been done).

The AI asked him what he had in mind, and Proyas entered a few prompts. “And then it starts criticising what I’ve entered. ‘Of course you need a protagonist, an antagonist, a three-act structure’.”

A little wounded, he typed back: “It’s OK, I know how to write a script. Now I need you to write one.”

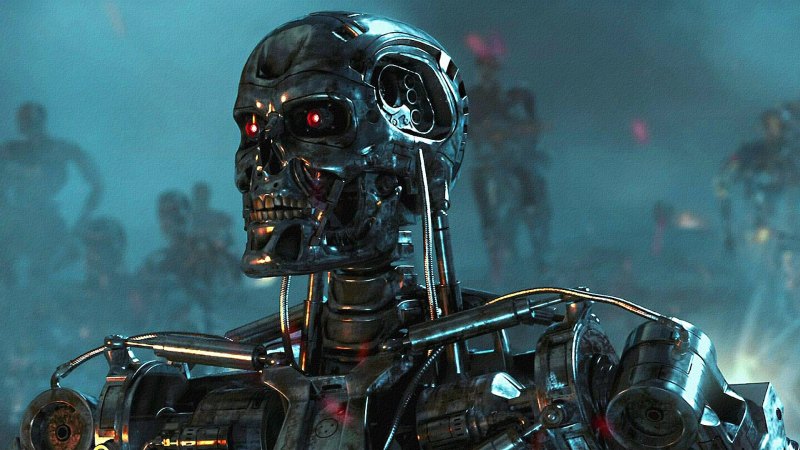

This image was created by writer-director-producer Alex Proyas as a character study for a forthcoming production, Rossum’s Universal Robots. Supplied by the filmmaker to illustrate the application of AI (artificial intelligence) in the movie business.Credit: Alex Proyas

But rather than turn out the next masterpiece, the AI and Proyas continued bickering. “I ended up in a completely stupid argument with it – ‘stop telling me the rules’. And then I realised I was arguing with a machine, and it was a complete waste of time.”

That’s far from the last encounter Proyas has had with AI as a filmmaking tool. He has used it to create posters, concept and character studies for a forthcoming production that he intends to shoot entirely in virtual environments (with real actors), but it does serve as something of a reality check about where the business is at with regards to the technological revolution that is at the heart of Hollywood’s biggest ever industrial dispute.

In short, it’s exciting, it’s full of possibilities and risks, but it’s far from the finished article right now.

The pace at which AI is evolving is remarkable, and that is a key reason so many people in the filmmaking business see it as a threat. When the 11,500 members of the Writers Guild of America went on strike on May 2, AI was a factor, but almost in passing. But by the time the 160,000 members of the Screen Actors’ Guild downed tools in July, it had become a headline cause.

Friend or foe? The rapid rise to prominence of AI has sent shockwaves through the filmmaking community.Credit: Dado Ruvic

Some of that may be strategic. If anyone knows the power of an apocalyptic scenario in which AI wipes out humanity, it’s Hollywood. But it is also rooted in very real concerns that AI could soon be writing screenplays, and that extras might never have the chance to progress to bit parts and then to leads because they have been scanned, stored and repeatedly redeployed as digital assets in return for nothing more than a day’s casual pay.

But on the flipside there are plenty of people in the industry who see infinite possibility in AI, not for unemployment and penury, but for enhanced creativity.

Kriv Stenders, one of this country’s most prolific filmmakers (his credits include Red Dog, the TV remake of Wake in Fright, and the recent ABC documentary series The Black Hand), has embraced AI as a writing tool, but not in the way you might imagine. Rather than asking Chat GPT to script a scene, he’s using the image generator Midjourney to bring the pictures in his head to life.

“It’s great for visualising a scene,” he says. “It’s like music – you can riff with it, and that gives you writing ideas. There’s this great feedback and resonance. It illustrates what’s inside your head.”

It works like this: Stenders has an idea for a shot he’d like to create. He types some words into the AI, offering settings, characters, reference points and style, and it generates an image. When it works, it helps move the story forward, possibly in a direction he hadn’t originally foreseen.

“It helps enhance the creative process, as opposed to replacing it,” he says.

Writer-director Kriv Stenders generated this image for a forthcoming family film using the following prompts: 1950s Woman Scientist in labcoat working in Outback old mansion clock tower making a time machine cinematic style Film Noir.Credit: Kriv Stenders

Though he can envisage a time when a new generation of filmmakers might be able to create entire projects artificially, that doesn’t frighten him in the least.

“It’s fair enough to ask questions about where this is all going,” he says, “but to me it’s not scary, it’s just part of the evolution of cinema, of the industry, of the interface. From the advent of the motion picture camera, to sound, to colour, to the internet, it’s all mind-blowing.”

It’s not just the speed of the evolution that takes his breath away, it’s the speed of application too. “I’ve always envied musicians who can go and record an album in a day, because film is so time-consuming and expensive,” says Stenders, who is using AI to help develop a family film, Antonio S. And The Mystery Of Theodore Guzman, based on the children’s novel by Odo Hirsch. “This is creating an immediacy that is so invigorating.”

For Kimble Rendall, a founding member of the Hoodoo Gurus and the director of shark-in-a-supermarket thriller Bait, the evolution of the technology now available to filmmakers means that a dream he has had since working as second-unit director on the Matrix sequels 20 years ago is now within reach.

Back then, he says, a lot of the action sequences were shot using virtual actors, and some of the footage created for the films ended up being used in the computer game Enter the Matrix, on which he also worked. (It’s worth noting that the key VFX person on those films was Kim Libreri, who is now the chief technology officer at Epic Games, whose Unreal Engine software is key to the move in recent years to virtual production, where sets are projected on large multi-screen LED walls).

Rendall has just released a proof-of-concept trailer for a project called Age of Beasts, in which he plans to push those tech-driven synergies to the limit.

Kimble Rendall has recently released a proof-of-concept trailer for Age of Beasts, which he hopes to develop as a game and a movie simultaneously.

“It’s using game technology to create a world, and using [digitally created] metahumans to create a story that’s 100 per cent in the computer. My aim is to create the assets to make games and films, to own the IP and to be able to create a game and a film simultaneously, reusing those assets.”

Rendall’s project is anchored more in the world of virtual production than AI, but the line between the two (and the related field of CGI, computer-generated imagery) is faint.

“There’s so much procedural AI – like predictive text on your phone – in everyday use that people sometimes don’t realise it is AI,” says Sophie Taylor, manager of Nant Studios’ world-leading virtual production facility at Docklands Studios Melbourne.

Procedural AI helps improve the resolution of an image, to sharpen blurry edges, to fill in the gaps between a starting render point and an end. The software has learnt how to do jobs that used to be done a frame at a time, but it’s operating as a tool, not as a creator.

“It’s the artistry of the person creating the image that drives it,” she says. “But what AI does help with is the iterations, getting through the development process of what the creative is after.”

It’s AI that drives the tech used in Sassy Justice, the deep-fake short film from Deep Voodoo, the studio backed by Trey Parker and Matt Stone, for example. But it’s their distinctive voice that makes it instantly recognisable as the work of the creators of South Park and Team America.

“We see it as a toolkit to enhance and enable creativity,” says David Balfour, head of teaching and learning at AFTRS (Australian Film Television and Radio School), where the next generation of filmmakers is grappling with the implications of AI. “We’re making sure our students are fully able to do the thing themselves, so they become good and ethical operators of prompts and good analysis and good tweakers. We’re preparing students for an industry where AI has been part of the toolkit that’s used in creating movies, and will continue to be, and will evolve and change.”

One thing that has rapidly become obvious, though: “When the students rely on AI too much, and they don’t put themselves in it, when there’s not an authentic person behind it, it doesn’t resonate.”

Screen composer Charlie Chan has trained AI to play in their own style, to remove much of the grunt work from the job.Credit: Chris Hopkins

Composer Charlie Chan has been quick to see the possibilities for the application of AI in their own work. “I have programmed my AI – named ChAI – by giving it a full classical musical education,” they say. “I loaded a million midi files into it, all the classical material in the public domain, then I gave it all my own compositions – all this in order that ChAI could develop the capacity to improvise the way I do.”

Chan has no concerns that they will be replaced by AI, or not just yet. “It’s reactive rather than proactive, at least at this stage. As a screen composer, there are so many deadlines in my process and the job, and having extra support in the form of a ‘mini-me’ is very practical. I believe the best future for the human race is one where we use technology to liberate ourselves from the process work and repetitive tasks, so we optimise our creativity.”

Retaining, and indeed enhancing, the role of the creator while they are deploying AI is central to the mission of Othelia, an Australian start-up that’s attempting to develop an ethical alternative to the large language models of the major tech players.

Those LLMs appear to have been trained by ingesting huge amounts of text created by authors, publishers, news organisations and others, without attribution or payment (indeed, the New York Times is considered launching legal action against Open AI – the company behind Chat GPT – with potential penalties of $US150,000 for each provable breach of copyright, potentially enough to force the wiping of the AI’s dataset).

Othelia’s Storykeeper platform is all about giving writers the tools of a Chat GPT without signing over the work they create with it.

“We’re focused on the small language model,” says co-founder and chief executive Kate Armstrong-Smith. “We don’t train off people’s data, we’re about allowing you to create and train your own bespoke worlds. If you can safely work with your material then you can quickly generate new episodes, you can work swiftly with your story.”

It has applications in the actual production process too, she believes, not just in the writing phase.

The founders of Othelia, Kate Armstrong-Smith and Joseph Couch, whose StoryKeeper AI platform enables writers to turn their characters, worlds and story arcs into data points for recombination across multiple storylines.

“If you want to rewrite with a new character, it can update the entire script and shooting schedule, all the consequences of that decision, across the whole story world, in real time.”

According to Fabio Zambetta, associate dean of artificial intelligence at RMIT University, that ability to iterate rapidly means “choose-your-own-adventure storytelling will go berserk”.

Like many others, he also thinks the potential for the tech to democratise the industry by lowering barriers to entry, and costs, is enormous.

“It’s going to save filmmakers precious pre-production time. Once you’re happy, then you press the button to go into production. It will be more useful for smaller players than bigger players.”

There will be job losses – “though I don’t think it will be that many” – but they will come anywhere AI can be deployed, which means filmmaking is really the frontline of a crisis we will all be facing soon enough.

“Pretty much any profession – a lawyer, an academic, a journalist – everybody will have an AI co-pilot,” he says. “All of these jobs have an element of more or less creative work, but the co-pilot will generate drafts, templates, starting points, and then we will go in there and do the creative work.”

The ethical and employment concerns are real, says tech entrepreneur Reggie Ba-Pe. But tech itself isn’t the problem.

Reggie Ba-Pe created a series of images in a couple of hours for a virtual Museum of Cosmic Chronicles and Antiquities.Credit: Reggie Ba-Pe III

“It isn’t AI that requests background actors to relinquish their image rights for a day’s work, nor is AI responsible for extracting other artists’ creations to reimagine them using generative models, and subsequently monetise these reimagined works to a vast audience,” he says.

The fact such things are happening, though, and are typically driven by Big Tech, underscores the need to establish an ethical framework for how AI is used.

“The cat is very much out of the bag,” says Ba-Pe. “We just need to make sure it doesn’t pee all over our bed.”

Nant’s Sophie Taylor agrees.

“I understand the concerns, but I don’t think you can stop it,” she says. “It’s a case of leaning into it, learning how to use it to your advantage, and making sure the legislation is there to protect people.

“There’s no point fighting it,” she adds, “but we can decide how we want to use it”.

Contact the author at [email protected], follow him on Facebook at karlquinnjournalist and on Twitter @karlkwin, and read more of his work here.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article