Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

It was not that long ago that the gas industry was unassailable in Australian politics. It had carefully positioned itself as a clean alternative to coal, its leaders had faced down efforts to increase taxes upon it, it had extracted subsidies for major export projects and had even spearheaded the nation’s economic response to the pandemic.

Now, following the release last year of a Gas Substitution Roadmap, which included plans to abolish regulations mandating gas connections in new homes and the dumping incentives for the adoption of gas appliances, the Victorian government has announced it will go further by banning gas connections to new homes from 2024.

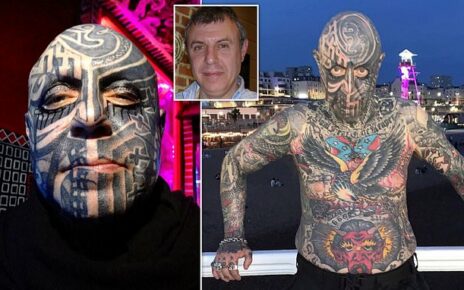

Victorian Energy Minister Lily D’Ambrosio: no longer cooking with gas.Credit: Joe Armao

So, things have changed.

Gas is now better understood as a greenhouse gas that burns more cleanly than coal, yet still contributes to global warming. Evidence is growing that burnt inside the home it can contribute to respiratory illnesses. And as exports are maintained and domestic supply shrinks, its price is rapidly rising.

Meanwhile, electric alternatives for gas heating and cooking are becoming more efficient, cheaper and customer friendly.

Confoundingly, new all-electric homes in Victoria are likely to actually emit more greenhouse gasses in the short term than those that use gas as well.

This is because much of the electricity used in Victorian homes is still made by burning coal.

But the grid is rapidly greening, and the sums will change, with electric-only homes running more cleanly.

Grattan Institute climate change and energy program director Tony Wood has done the sums. At present, the average all-electric home in Victoria would generate about three and a half tonnes of greenhouse gasses, compared with about three tonnes for one that used gas for cooking and heating.

But over 10 years the electric home would generate around 20 tonnes compared with 28 tonnes for a dual fuel home.

“This is good policy,” said Wood. “It is good energy policy because it actually starts to drive us towards where we’ve got to be in reducing costs in the system. It’s a good social policy because it produces lower prices for people, particularly those who can’t afford it.

The gas industry is facing new regulatory changes.

“It’s a good health policy because there’s at least a lot of evidence about pollution from gas in the home.”

The decision is being warmly received as a crucial climate policy too.

It is clear, says renewables and electrification advocate Saul Griffith, that Australia cannot be decarbonised without its homes being decarbonised, and homes cannot be decarbonised without gas being removed.

The federal government has committed to cutting Australia’s emissions by 43 per cent by 2030 and to reach net zero by 2050. Soon, it must announce updated and more ambitious targets.

The five million Australian houses with a gas connection account for about 17 per cent of the fossil fuel that is consumed each year.

Griffith says the industry has fought such actions hard around the world, with more than a dozen Republican-governed states passing preemptive laws to ban bans on gas.

So far in Australia only the ACT has moved to announce an end to new connections, which begins in November. Victoria will follow suit in 2024.

Tim Buckley, director of Climate Energy Finance, a pro-renewables consultancy, says the decision signals a broader shift in attitudes towards gas.

Having sold Australian gas offshore more cheaply than it did domestically, says Buckley, the industry is losing its social license.

If that is the case it is now an easier target for reform by governments determined to cut greenhouse gas emissions and household costs.

Get the day’s breaking news, entertainment ideas and a long read to enjoy. Sign up to receive our Evening Edition newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Environment

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article