Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

On a late-summer day in 1967, my mother stood by the yellow mailbox of our house in Concord, reading a government pamphlet about the coming referendum.

It was hot, I remember that. The driveway asphalt stuck to my thongs. I wondered what was so important in that letter that Mum would stand in the sun and read it, rather than carrying it inside to the cool.

“Australians always vote no,” she told me. “But we’ll all vote yes for this one. It’s the right thing to do, and about time.”

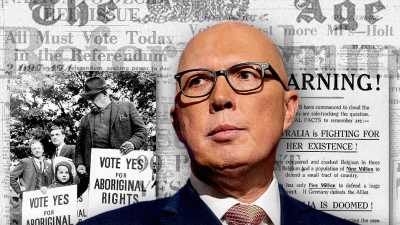

Peter Dutton wants a No vote in the 2023 referendum. In 1967, 90 per cent of Australians said yes to Indigenous rights.Credit:

She was correct. Over 90 per cent of Australians voted yes when they went to the polls that May. I was 11, old enough to understand my parents’ pride and relief that the country so overwhelmingly supported this first step towards reconciliation.

What I’m not understanding is what’s happening now. Since I left Australia in late May, support for the Voice referendum has been wavering, something that, from outside the country, seems entirely baffling. Attempting to follow the debate from a distance is difficult, since it isn’t so much a debate as a series of Alice in Wonderland-style non-sequiturs.

When the referendum was announced, I was as sure as my mother had been in 1967: of course, we’ll all vote yes for this one. It’s the right thing to do. But then, over a dinner in Haberfield last December, a friend’s contrary opinion startled me. “It’s going to fail,” he predicted gloomily. This man, a prince of the progressive punditocracy, believed that Prime Minister Albanese had made a tactical mistake. Wide community support for the idea, he said, should have been built before announcing the referendum, not drummed up after. He believed that reactionary forces would be able to create and exploit uncertainty around the meaning of what was proposed.

Peter Dutton’s anti-Voice rhetoric has Trumpian cadences.Credit: Joe Benke

I thought he was crackers. After all, you don’t rise to the top of the NSW Labor Party by having a poor grasp of tactics. That month’s polls seemed to support me. Australians were for this; how could they not be? It was so small a thing: so modest an ask, so nugatory a change.

And yet so necessary. How else could 3 per cent of the population be heard, when their interests and needs differed in important ways from the kinds of issues that win seats and put politicians in power? One thing’s certain: they never have been.

So I did not see how anyone could be against our most underrepresented and disadvantaged people being able to express an opinion and offer guidance on laws and policies that directly affected them. Laws and policies that absent any such mechanism for consistent consultation have abjectly failed for decades.

So small a thing. So tiny a change. Another baby step on the path of the journey begun in 1967. It was underestimating Australians to even think they would not support this.

But then the Nationals said no. And soon, so did Opposition Leader Peter Dutton, a man who has forged an entire career out of divisiveness. The man who wanted to welcome as refugees white South African farmers, even as he locked up actual refugees in inhuman conditions. A man who railed against marriage equality, who made a joke of climate change, who has been on the wrong side of every moral issue in the nation. Most Australians know this: that’s why his approval rating is in the toilet.

And that’s why I am baffled that his nonsensical arguments are gaining traction. Dutton characterises this very small change as “massive”, “divisive”, “dangerous”, but he never says what these fierce dangers – from a small group of people giving non-binding opinions – might be.

From my vantage point in the United States it is easy to hear the Trumpian cadences in his diction, the familiar trope of accusing your opponent of the very crime of which you yourself are guilty.

The Voice will create division, says the man who boycotted the national apology to the stolen generations, a blatantly divisive gesture during a moving moment of parliamentary unity. The Voice will re-racialise Australian society, he says, while he has racialised issues at every opportunity. (African-Australian gangs “terrorising” Melbourne; Malcolm Fraser’s “mistake” in admitting Lebanese immigrants.)

And, also in mimicry of Trump, Dutton rails against Aboriginal “elites” from the poolside of his two-hectare estate in the Brisbane hinterland, while he counts up the receipts from his extensive property portfolio.

It’s painful when one contrasts the glib slogans of Dutton with Megan’s Davis’s painstaking account, in the most recent issue of Quarterly Essay, of how much deep consultation went into the Uluru Statement from the Heart, for which the Voice is the first step on the way to treaty and truth. Davis, a professor of constitutional law, details the trek she and others made to a dozen regions across the continent to engage First Nations communities in three-day long dialogues, setting out the various options on which then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and opposition leader Bill Shorten had agreed.

Every one of these regional dialogues ranked the Voice as their first priority.

So, yes; some individual First Nations people are against the Voice, and for widely differing reasons, but the vast majority – currently 82 per cent – are for it. Eighty-two per cent. That’s a lot of voices. I hope the rest of us can hear them.

Geraldine Brooks is a US-based, Pulitzer Prize-winning Australian author and journalist.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article