Our reviewers cast a critical eye on the biggest performances around town.

FENCES

Wharf 1 Theatre, March 30

Until May 6

Reviewed by JOHN SHAND

★★★★½

We build fences around our countries, our jails, our houses and our hearts. As Bono observes in August Wilson’s potent play set in the 1950s, “Some people build fences to keep people out, and other people build fences to keep people in.” Rose has her husband Troy erecting a fence around their yard throughout this play. It’s a stop-start process, partly because Rose wants to keep Troy in, and Troy wants to keep others out.

Bert Labonte and Zahra Newman are reunited as husband and wife in Fences.Credit:Daniel Boud

Having played the husband-and-wife leads when Sydney Theatre Company presented another brilliant African-American play last year, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, Bert Labonte and Zahra Newman are reunited in the same relationship here.

As with Raisin, Labonte’s character is the epicentre, and here he turns in an even more riveting performance. The other characters must navigate their way around him as carefully as ships encountering a mine in a narrow strait because Troy doesn’t take a lot of prodding to explode.

When she learns Troy has been unfaithful, Rose describes the soil of his soul as being hard and rocky, yielding nothing. But Troy has been worn and weathered by his childhood, his father, World War II, violence, jail, failed relationships, illiteracy, poverty, menial work, fatherhood and, above all, disappointment that, because of racism, his outstanding talent as a baseballer didn’t lead to a stellar career.

But for all the baseball metaphors that litter Troy’s dialogue, fatherhood sits irascibly in the foreground of Wilson’s play. When Troy speaks of the relentless ferocity of his own father, he’s impervious to the irony. Fatherhood is presented as a trial, but where Troy sees it as a test of manhood, Wilson means it to be a test of empathy and sympathy.

Labonte gives Troy a loose-limbed swagger laced with enough braggadocio for the character to convince himself he’s always in the right. He can be genial with his friend Bono (Markus Hamilton), caring with his brother Gabriel (Dorian Nkono) and even playful with Rose, but with his sons, family is a synonym for friction.

When his youngest, teenaged Cory (Darius Williams), asks his father why he never liked him, Troy’s response is, “Who the hell said I gotta like you?” He then viciously ends Cory’s budding football career, whether that’s to save the kid from the racism and disappointment he endured himself, or to avoid being outshone. His older son, Lyons (Damon Manns), sired with another woman before Troy was jailed, is a jazz musician who implores his father to come and hear him play, but he will never bestow such an overt nod of approval.

If all this makes Troy sound like an ogre, Labonte’s exceptional performance humanises the husk, and makes us understand – even if we can’t always forgive – the failings.

Newman is again a worthy foil, giving us a Rose who credibly still tries desperately to nurture their love, despite everything. Hamilton, Williams and Manns are all superbly realised in a production by director Shari Sebbens that reaches from assured to inspired, especially with Labonte and Nkono. Gabriel had part of his skull blown away in the war, and Nkono rends or warms our hearts at every turn.

Jeremy Allen’s literal set is a joy of its own, exquisitely lit by Verity Hampson, while composer Brendon Boney takes an admirably minimalist approach in an era when few dare present a play uncluttered with music. Fences deserved the 1987 Pulitzer Prize, and this production does it proud. Please see it.

The end of the world never sounded better

King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard

Luna Park Big Top, March 30

Reviewed by MICHAEL RUFFLES

★★★½

If this is the apocalypse, it sounds terrific.

King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard might have skipped Bluesfest, but they arrived at Luna Park on Thursday ready for blast-off. And their psychedelic fusion of prog-blues-electro-metal-whatever (often laced with warnings of climate change catastrophe) was by turns bombastic, blissful and electrifying.

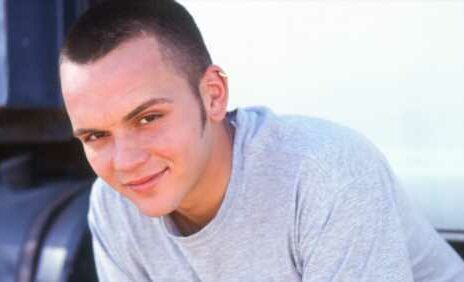

Stu Mackenzie of King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard. The band has boycotted Bluesfest.Credit:Rick Clifford

An almost laidback early jam quickly gave way to the one-two punch of Wah-Wah and Road Train, the thundering climax to 2016’s relentless Nonagon Infinity.

Newer, and longer, material soon came to dominate the set. In studio form, Hypertension is a 15-minute monster; here it felt snappier and snazzier as frontman Stu Mackenzie whipped his guitar over his head, and its myriad detours were dazzling. Brilliant too was Iron Lung, when Ambrose Kenny-Smith was unshackled from the keyboard to stalk the stage and snarl out a metaphor for a suffocating Earth.

Ice V, also from last October’s batch of three records (they’re prolific), offers the hope that you can dance away the impending doom.

When 90 minutes is divided into just 11 songs, there can’t be too many missteps. A charming but overlong sojourn into electronica (Shanghai) and a hip hop-flute-metal mashup that could have gone a lot worse in other hands (The Grim Reaper) were the weakest links, but were hardly bad. They served as a reminder of the band’s versatility; King Gizzard are often brilliant, but even when they’re not they’re never boring.

But the gravity of rock won in the end. The mesmerising Crumbling Castle and pulsating The Fourth Colour from Polygondwanaland (2017) brought the set to a guitar-laden, psychedelic crescendo. Last was new track Gila Monster, a rollicking slab of metal that hints at heavier things ahead.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article