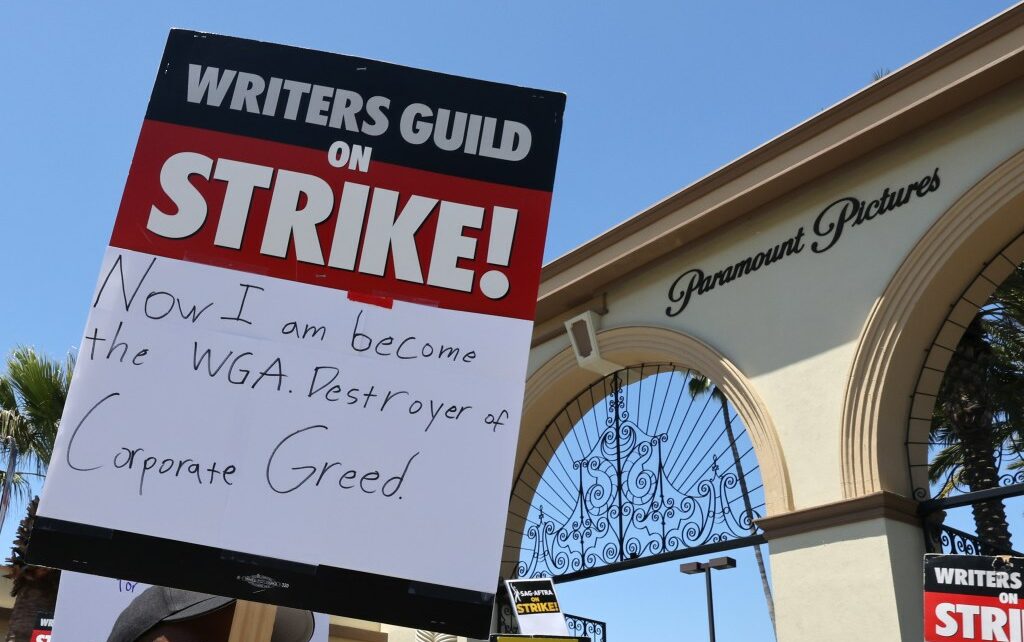

The Writers Guild of America responded on Tuesday to the latest proposal from the studios, as the sides continue to try to resolve the three-month old writers’ strike.

While the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers has made some concessions, including agreeing to provide streaming viewership data, the studio group has not agreed to a key WGA demand for a minimum staff size for TV writers rooms.

The AMPTP at first refused to even consider the idea. But in it latest proposal, it offered to give showrunners flexibility to hire a certain number of writers, depending on the budget of the show. The WGA, meanwhile, has continued to make clear that it wants a fixed minimum staff size for all shows.

The two sides remain at odds on a host of other issues as well. But the TV staff size proposal is shaping up as a key hurdle to getting an agreement.

The WGA places a premium on solidarity. But within the guild, there’s been some private dissent over the proposal, with some showrunners telling Variety that they think it is the “wrong fight” and should not be the reason that the strike is prolonged.

The guild includes 11,500 members, and in a group so large, it’s natural that not everyone is going to see eye-to-eye on every issue. But Variety spoke with seven writers with varying levels of experience — including several current or former showrunners — who were willing to explain their opposition on the condition of anonymity.

Several expressed concern that the guild’s proposal would take authority away from showrunners.

“Nobody asked for this,” said one prominent showrunner. “Every showrunner I know is against this. It doesn’t make sense to anybody.”

Another writer added: “All the showrunners that want a staff should be given a staff. I don’t think it’s important to force those few that don’t want a staff to have a staff.”

The WGA proposed in the spring that TV shows should hire a minimum of six to 12 writers, depending on the number of episodes in a season. At its meeting on Tuesday, they agreed to reduce that ask by one writer — but would not forgo the basic structure.

Several showrunners told Variety they did not want to be forced to hire writers who are not needed. In its worst form, they say, that would amount to “featherbedding,” an illegal labor practice in which employers are required by union rules to hire workers who do no work.

“It’s creating make-work jobs,” said another writer.

This writer said he’d worked on shows where his contributions were essentially ignored, and he fears that’s what would happen to writers who are hired under a staffing mandate.

“It’s an awful thing to go to work every day and know you’re being paid to sit around and do nothing. It doesn’t actually help your career long-term,” he said. “I think that people think they want these guaranteed jobs. But from my experience, they really don’t. It’s a poisoned chalice.”

The WGA also wants the writing staff to be guaranteed three weeks of work per episode and that half the staff is employed throughout production. In addition, the guild is seeking a 20% increase in minimum compensation for writer-producers. The guild argues that mandating these parameters is essential to preserving the writers room from studio cost-cutting.

“We will not give up on any one of those principles,” Chris Keyser, the co-chair of the negotiating committee, told Variety in an interview in June. “Without any one of them the whole thing falls apart.”

With the notable exception of “Yellowstone” creator Taylor Sheridan, no one has been willing to publicly oppose the idea of a mandatory minimum staff. The WGA has stressed the importance of solidarity during the strike, and some fear being branded a traitor to the cause.

Supporters of the proposal have argued the showrunners are facing pressure from the studios to get by with as few writers as possible. That’s particularly true in “pre-greenlight” mini-rooms, where a handful of writers will be tasked with breaking an entire season of a show in just a few weeks.

The WGA proposal is intended to codify a room size that had been standard on most shows for decades.

“It’s not acceptable for the companies to just say, ‘Well now we want you do all the work with fewer people in a smaller amount of time and that’s fine,’” Ellen Stutzman, the guild’s chief negotiator, told Variety earlier this year. “That’s a major problem for television writers.”

Some opponents of the proposal say they haven’t heard from showrunners who have this concern. Others acknowledge the validity of the issue, but say the proposed solution is misguided. Several said that the showrunners will likely end up just hiring their friends for no-show jobs.

For broadcast shows, which typically have 22 episodes, the WGA would mandate a minimum of 12 writers. Most shows already exceed that threshold, according to the showrunners who spoke to Variety.

On streaming and cable, where seasons can run eight to 10 episodes, the guild would mandate seven or eight writers.

“I don’t need that many writers,” said one showrunner who was working on such a show until the strike began. “I don’t want some people coming in who have been mandated… If I’m forced to hire two or three more people, they will be seen as a burden by other people in the room.”

Another writer, who works on limited series with one or two other writers at most, argued that the guild should protect creative rights and compensation, but not interfere in how showrunners do their jobs.

“It’s the wrong fight,” the writer said.

Some supporters have said that writers rooms give younger writers the opportunity to learn from more experienced people. But opponents have countered that may not be appropriate for all shows. “Not all hospitals are teaching hospitals,” one said.

Another showrunner argued that there are creative reasons why writers rooms might not work for every show. In some cases, the challenge is establishing a clear authorial voice, this person argued, and having “too many cooks” would make that more difficult.

“When you think of some of the most creatively daring shows on TV, many of them have been written by a single writer,” the showrunner said. “The more distinct the voice is, the better the show becomes.”

The WGA itself has lauded the creative achievements of solo writers. The guild gave an award earlier this year to Mike White, the solo writer of “The White Lotus.” The guild has also given awards recently to auteur-driven shows including “Chernobyl,” “The Queen’s Gambit,” and “Mare of Easttown.”

Solo writers are more the norm in the U.K., which has recently produced “Fleabag” and “I May Destroy You,” two critically-acclaimed shows written by Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Michaela Coel, respectively.

Showrunners say the range of episodic series that are produced these days make it impossible to have a one-size-fits-all prescription.

“Each project is very different. Experienced showrunners know their needs on each project,” the showrunner said. “I want to be in charge of my own show. I don’t want to have my union telling me how to run my show.”

On the picket lines, support for the idea is easy to find. Many writers carry signs saying “Room size matters.”

Carrie Rosen, a mid-level TV writer, told Variety outside Disney in May that the issue is her top concern. “I am among the writers that have been having a hard time sustaining a lifestyle,” she said. “Having a required number of people on staff seems great… There are so many showrunners I know that would have loved to have more people on their shows, but just didn’t have the money for it.”

Writer employment surged during the streaming era, according to WGA data, rising 76% from 2008 to 2019. But the industry is now facing a contraction, as streamers and studios have moved to rein in their content spending.

Some of the showrunners who oppose the idea said they believe the support for it comes from writers who fear being left behind.

“When all is said and done, the estimates are that the number of working TV writers is probably going to shrink by 30-40%,” said the writer who warned about “make-work” jobs. “People are scared. People who staffed once in 2020 or 2019 and not since are really scared that they’re not going to work again. They’re right to be scared, because it’s a game of musical chairs and people are taking the chairs away. This is being promoted as solution to that. I don’t think it’s viable.”

Several writers have said that they had been warned to keep any opposition to the proposal “in house,” so as not to undermine the WGA in negotiations. But they said their concerns had been ignored when they tried to engage with guild leadership.

Several said they are far more interested in getting a much-improved residual on streaming platforms.

“The only issue that should be going on in a strike is money, money, money,” said the first showrunner, who argued that withdrawing the staff size proposal would help create momentum to get a deal.

A seventh writer said he hoped the leadership got the message that the strike should not be prolonged over a staffing minimum.

“This is not the reason we should remain on strike,” he said. “I hope they’re willing to drop it to get things that actually matter.”

Craig Mazin, who wrote “Chernobyl” by himself and wrote “The Last of Us” with Neil Druckmann, was somewhat cagey when asked about the staff-size proposal by Variety in July.

“I may not agree on everything that the union is looking for,” he said. “But then again, if you agree on everything that your leaders put forward, you’re probably just a robot.”

Cynthia Littleton contributed to this story.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article