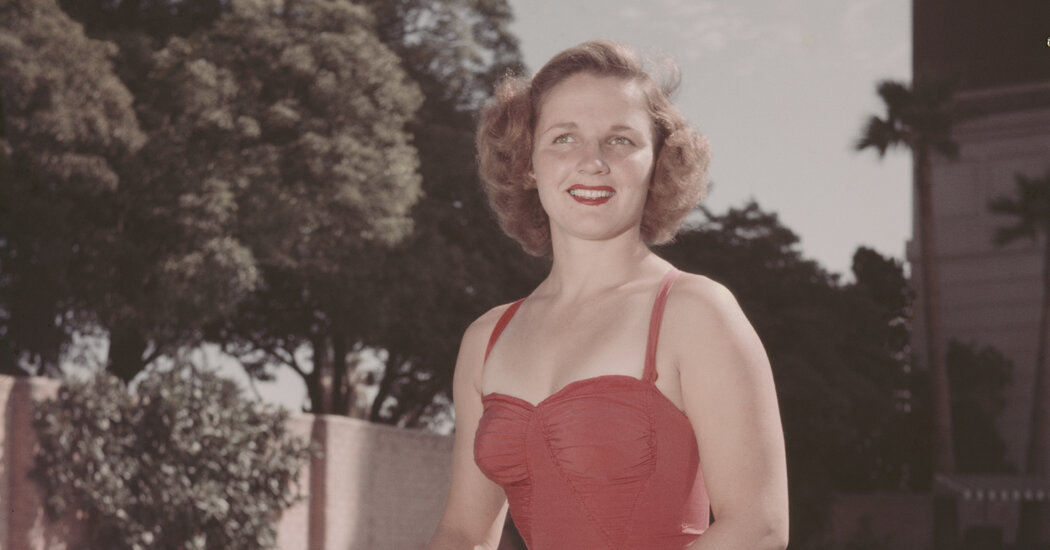

Pat McCormick, the first diver to sweep the gold medals in two Olympics, died on Tuesday at an assisted living facility in Santa Ana, Calif. She was 92.

Her daughter, Kelly Robertson, confirmed her death. She said her mother had a number of ailments, including health problems and dementia.

At the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, McCormick won the women’s 3-meter springboard and 10-meter platform competitions, the only ones being held for women at the time. In 1956 in Melbourne, Australia, eight months after the birth of her first child — and with her husband, Glenn McCormick, as the team’s coach — she won them both again.

Her feat was unequaled until another American, Greg Louganis, captured the 3-meter and 10-meter titles at the 1988 Seoul Olympics four years after doing it in Los Angeles.

McCormick might have had the chance to accomplish that feat three times: She had passed up her Wilson High School graduation in 1948 to compete in the United States Olympic trials, but she missed making the team by less than a hundredth of a point.

“Because of that failure,” she told The Los Angeles Times in 1987, “I started dreaming about the next Olympics. In ’48, I just wanted to make the team. I was standing there crying after I came up short, and that’s when I decided I would win a gold medal in the next Olympics. Then I thought, ‘Why not go to two Olympics and win four gold medals?’”

McCormick chose to end her career after the 1956 Olympics, having won more than two dozen national championships and two Pan American Games gold medals. She finished on a high note: That year she became the first female diver to win the James E. Sullivan Award as America’s outstanding amateur athlete, and only the second woman. (The swimmer Ann Curtis had been the first, in 1944.)

In 1965, McCormick was in the first group of inductees in the International Swimming Hall of Fame. She was later named to the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame and the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame.

In 1985, in an interview with Jim Murray of The Los Angeles Times — who called her “one of the larger-than-life stars of Olympic history,” on a par with Jesse Owens and Jim Thorpe — McCormick reflected on her career and looked back on what she called her “post-Olympic blahs”:

“Consider that some athletes have never had a conversation in their lives that didn’t have to do with swimming or diving or running or jumping. They’re interested only in their muscles, their times, their scores. Lots of people can tell you how high to jump, how fast to run, how deep to dive. But nobody tells you that you have to fit into that larger world, a world you pretty much ignored or took to be unimportant.

“You lose your identity. You have no tools. The pitfall is that the athlete gets so absorbed in his own world, his own event, that everything outside it seems trivial. To become the best in the world at what you do requires the kind of tunnel vision of a stalking beast.”

McCormick tried to avoid that trap. Lacking the time to be a full-time college student, she took classes for 13 years and eventually earned a degree at Long Beach State College (now California State University, Long Beach).

Patricia Joan Keller was born in Seal Beach, Calif., on May 12, 1930. She began diving at a young age but did not begin formal diving training until she was 17 and was invited to work out at the Los Angeles Athletic Club with Sammy Lee and Vicki Draves, both future Olympic medalists. She traveled there by trolley, paying the fare with money her mother had made giving tea-leaf readings. She eventually did 100 dives a day, six days a week, 12 months a year.

In 1951 she became the first diver to win all five national championships. But that same year, she learned that diving had some serious hazards: A doctor examining her found numerous lacerations, welts and scars, as well as a loosened jaw and chipped teeth. “I’ve seen worse casualty cases,” he said, “but only when a building caved in.”

In 1949 she married Glenn McCormick, a pilot for United Airlines who coached divers on his days off. They divorced in 1974, but there had been tension in their marriage long before that: She once said that winning her fourth gold medal “was a sign that I could proceed with my life,” but that “coaching became Glenn’s whole life, his mistress, his everything, and I was just another person.” Glenn McCormick died in 1995.

After McCormick retired as a diver, she received movie offers but rejected them, although she did do some modeling for a swimsuit company. She focused her energy on running a diving camp, where one of her prize students was her daughter, Kelly, who would win a silver medal on springboard at the 1984 Olympics and a bronze in the same event in 1988. She also became a motivational speaker, and her Pat McCormick Educational Foundation steered at-risk youths toward high school graduation and a college education.

In addition to her daughter, McCormick is survived by a son, Tim; six grandchildren; and several great-grandchildren.

In her years as a speaker, McCormick preached that athletes needed to take responsibility for their lives. “When you step up on that victory stand,” she said in 1985, “you’re going to be deserted. All the support systems you had are going after their next project. They can’t tell you how to handle success; they can only tell you how to achieve it.

”The trick is to stay on that victory stand. Never step down from it.”

Frank Litsky, a longtime sportswriter for The Times, died in 2018. Peter Keepnews and Alex Traub contributed reporting.

Source: Read Full Article