- College football reporter.

- Joined ESPN.com in 2008.

- Graduate of Northwestern University.

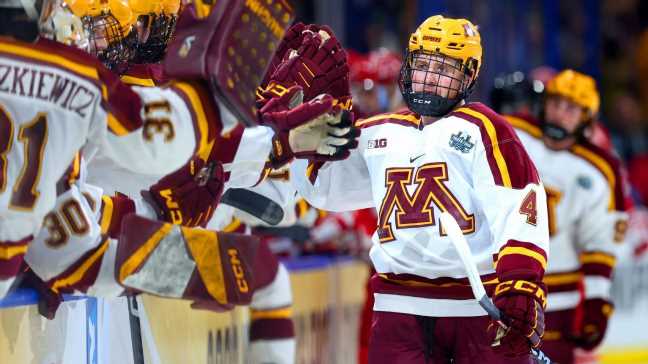

Editor’s note: This story was originally published March 23, before the start of the NCAA men’s hockey tournament. Minnesota will play in the national championship game Saturday.

MINNEAPOLIS — The markings of greatness are scattered around 3M Arena at Mariucci, home to University of Minnesota hockey.

A glass case in the main lobby displays the 2003 NCAA championship trophy. Those walking the arena’s underbelly pass banners recognizing Minnesota’s back-to-back national titles in 2002 and 2003. A picture in the players’ lounge shows captain Grant Potulny holding the 2003 trophy on the ice in Buffalo, New York.

Other reminders aren’t collecting dust. Coach Bob Motzko was an assistant when the Gophers twice reached the summit of college hockey. Paul Martin, an alternate captain on the 2003 squad and a 14-year NHL veteran, was a graduate student manager with the team.

“You can’t help but be in this program, walk down the halls and see all the trophies,” Motzko said.

Minnesota hasn’t gripped an NCAA trophy in 20 years, a frustrating famine for the flagship college program in a hockey-obsessed state. Eleven teams have claimed national titles since the last Gophers triumph, including Minnesota Duluth, who has won three, and rivals North Dakota and Wisconsin (one each). The Gophers have been close, reaching the championship game with the nation’s No. 1 team in 2014 before falling to Union, and making four Frozen Four appearances, including last year, when they were blitzed 5-1 by Minnesota State in the semis. But 20 years is 20 years.

“I was curious myself,” defenseman Jackson LaCombe said of the lull. “Obviously, they were close, but there are so many great teams. It’s a hard thing to win.”

Minnesota has a team poised for a title push. The Gophers have been ranked No. 1 or No. 2 in the country much of the season and received the top seed in the tournament.

Minnesota cruised to the Big Ten regular-season title and never dropped consecutive games. Two players, forward Matthew Knies and center Logan Cooley, are top 10 finalists for the Hobey Baker Award, and two others, LaCombe and defenseman Brock Faber, were nominated.

Minnesota ranks second nationally in goals per game (4.08). The team’s young, dynamic line of Knies, a sophomore, and freshmen Cooley and Jimmy Snuggerud are quasi-celebrities, getting recognized at Minnesota Wild games and at other spots around campus. The defensive core, led by LaCombe and veterans who put their pro careers on pause, is “different than anything I’ve seen,” Motzko said, and has held opponents to 2.28 goals per game (ninth nationally). There are inspiring stories such as that of Justen Close, who barely played his first two seasons and was a semifinalist for the Mike Richter Award as the nation’s top goaltender this year.

The Gophers are gifted and gritty and play an exciting style that has filled the seats at Mariucci, where they have the nation’s second-highest average attendance and set a program record for a weekend series with 20,755 fans watching them play Michigan. They have a homegrown roster that understands what a championship would mean to the state, and key non-Minnesotans who add to the mix.

Without an obvious flaw, they enter the tournament as a popular pick to win it all.

“Our goal in mind is to win a national championship,” Snuggerud said. “Every single guy on this team knows that.”

THE FIRST COMPONENT to Minnesota’s championship pedigree was the ability to grow old. The best college hockey teams are veteran laden, but the NHL has increasingly plucked younger players off promising teams. The delayed start to college for many players because of junior hockey — 20-year-old freshmen aren’t uncommon — adds to the retention challenge. Minnesota’s rosters have skewed a bit younger than some of its competitors.

When the 2021-22 season ended, Motzko expected top defensemen Ryan Johnson, Faber or LaCombe — perhaps all three — to go pro. Johnson was a first-round draft pick of the Buffalo Sabres in 2019, while LaCombe (Anaheim Ducks) went in the second round that year and Faber (Los Angeles Kings) was a second-round selection in 2020. (His rights have since been traded to the Wild.)

“You’re going to at least lose one,” Motzko recalled thinking after last season. “And you keep all three. It’s been a great benefit to us.”

The blue line retention is a link to Minnesota’s past championship teams, which kept defensemen Keith Ballard, Martin and Jordan Leopold. A second-round pick in 1999, Leopold chose to remain at Minnesota and won the Hobey Baker with 48 points in 2002. Ballard and Martin starred for the 2003 team.

The difference with the current group is it goes seven deep. Junior Mike Koster has more than doubled his career points output with 25 this season, and freshmen Luke Mittelstadt, Ryan Chesley and Cal Thomas are a combined plus-40.

“They move the puck really well and add talent to the offensive zone,” Close said. “It makes my life a lot easier for sure. The amazing thing is so many of them are still so young and they’re so talented already. Me being the oldest guy on the team, 24, gosh, seeing where some of these guys are at 18, it’s astounding.”

Minnesota’s defensive core is distinct, but Motzko maintains that the team has an offensive bent. Cooley and Snuggerud, the No. 3 (Arizona Coyotes) and No. 23 picks (St. Louis Blues) in the 2022 NHL draft, have combined for 39 goals and 101 points. Their talent popped immediately, but once they “grew their whiskers,” Motzko said, and started vibing with Knies and the other veterans, the magic began.

Cooley has scored at least one point in all but five games he’s played, including a current stretch of 13 straight, and had a five-point period (four assists, one goal) Feb. 17 at Penn State. Snuggerud has 15 multipoint performances. Knies, a second-round draft pick of the Toronto Maple Leafs in 2021, is tied for ninth in goals per game (0.58) with an NCAA-best seven game winners.

“That top line is a big reason the fans are coming; we’re selling out because of those three,” Faber said. “They do things that I could never even think about doing, night in and night out. There’s so much chemistry between the three of them, it’s crazy to watch.”

Before Minnesota, Cooley and Snuggerud played on the same line in the USA Hockey National Team Development program. They’re both high draft picks with promising pro outlooks, but Cooley said a key was “not coming in being cocky.”

“We have a lot of high expectations for ourselves,” Cooley said. “We’re just trying to do whatever we can on the ice to help this team win, eventually, a national championship.”

AS COMMISSIONER OF the Central Collegiate Hockey Association, Don Lucia is focused on the teams in his league, but he still keeps tabs on the Gophers. He has a standing call on Sundays with Motzko, his chief assistant at Minnesota from 2001 to 2005.

Lucia coached Minnesota from 1999 to 2018, reaching five Frozen Fours and winning the two national crowns. His best teams, like the current Gophers, featured a mix of seasoned defensemen and dynamic young players, such as freshman winger Thomas Vanek, who led Minnesota with 62 points, and freshmen Gino Guyer and Tyler Hirsch.

“They have the ingredients,” Lucia said of Minnesota’s 2022-23 squad. “They have one of those defensive cores that’s almost generational, they don’t come around very often. Their upperclassmen elected to come back. Then, much like the ’03 team, they’ve got the special freshmen. We had Vanek, who scored big goals to beat Michigan in overtime in the semifinals. [Motzko has] that with Cooley and Snuggerud.

“There’s no question they’re one of the teams that have a great chance to win it all this year.”

After Minnesota won its second title under Lucia and the fifth in school history, there was a natural inclination to expect more. But history told otherwise. Before the 2002 title, Minnesota hadn’t won since 1979.

Other power programs have had similar title gaps. Boston College went from 1949 to 2001 without a championship. Michigan hasn’t won one since 1998.

“In the ’70s, ’80s, it rotated, but there were probably eight or 10 teams that really had a chance to win a national title,” Motzko said. “In today’s era, there are 25 that could win it if they could get in [the tournament]. The depth of college hockey is far stronger than it’s ever been.”

Minnesota remains the top talent-producing state for Division I hockey, but there’s more than one top-shelf option for elite players. Minnesota Duluth won national titles in 2011, 2018 and 2019, while Minnesota State and St. Cloud State are the past two NCAA runners-up.

“Growing up, they weren’t as prominent of programs,” said Martin, a native of Elk River, Minnesota. “The TV rights were only on for the Gophers. You still get a lot of the premier players [at Minnesota]. It’s just a little bit tougher in today’s landscape. But you definitely expect to have a couple more championships within 20 years.”

Martin believes the current group of Gophers has a chance. Like the title teams he played on, Minnesota has star power spread among positions, age groups and lines.

Being around the players daily, Martin sees similar bonds to the title teams.

“The ability for guys to kind of put aside their own personal agenda — especially these guys, they all are extremely talented — for the betterment of the club, and an opportunity to win a national championship, is what they’ve grown to do all year,” Martin said.

The opportunity is there, but postseason hockey can be humbling. The game is “way grittier,” Faber said, and scores are often close. The most talented teams don’t always win.

“The scary part of the NCAA tournament is it’s one and done,” Lucia said. “If you happen to have an off night, unfortunately that’s the way it ends. But they’ve put themselves in a good spot. They know this is a special group, and I’m sure if they don’t make a deep run, it will be disappointing.”

FABER GREW UP in the Minneapolis suburb of Maple Grove and spent many Friday and Saturday nights in the stands at Mariucci. He loved watching stars such as Kyle Rau and Nate Schmidt, two in-state products who played for the Gophers and went on to the NHL.

Despite being in diapers for the 2003 championship run, he has seen highlights.

“When I was a kid, games were always close to sold out, student section was great, the band,” Faber said. “It feels like yesterday, I was sitting in the stands, watching them play, cheering them on. It was a dream of mine. It was all I thought about.”

Minnesota games have become an event again, especially this season. Motzko is adamant that Gopher fans never went away.

“We had to give them a reason to come back,” he said. “Post-COVID, there has really been an uptick in the student involvement. Our student section is nothing like I’ve ever seen. The [Doug] Woog era had these kinds of crowds, the Lucia era had these kinds of crowds and now we’re getting them back.”

Andrew Mercado spends home games in the front row of Minnesota’s student section, sporting a bleached mullet that he’s been growing since 2019. Mercado is from California but became a Minnesota fan about a decade ago, after his dad returned from a conference in Minneapolis with Gopher merch.

A hockey fanatic, Mercado began following the Gophers and last year transferred to Minnesota from a community college. Crowds initially were smaller as Minnesota welcomed back fans after COVID-19, but Mercado saw the student section gradually fill. This season, he and his roommates routinely arrived for games two hours before puck drop.

“When you go to the game, there’s going to be a buzz, there’s nothing like it,” said Mercado, a senior majoring in English. “My roommates and I, we always talk about how if we can get the first goal and get the building going, it’s going to be a tough game for the other team. We’ve built an environment that I never thought I would experience.”

Mercado lists Mason Nevers’ winning goal in overtime against North Dakota as the season’s top moment. He and his roommates avoided any “creative spring break trips” to save up for a potential Frozen Four visit to Tampa, Florida, and a chance to witness history.

“Just knowing how miserable my roommates are, they’re all from Minnesota and they’re talking about all their Minnesota sports teams always let them down,” Mercado said. “When we go to a basketball game, we know we’re not going to be the best, but we always say, ‘We’re a hockey school, we’re a hockey school.’

“For the students, for everyone in Minnesota, it would be great for us to win a national championship.”

DURING A DECEMBER practice at Mariucci, Motzko glanced up at the only retired jersey in team history, the No. 8 belonging to John Mayasich. Motzko got an idea.

Minnesota was headed north to Bemidji for an exhibition game. Motzko wondered if Mayasich, 89, was home in Eveleth, the iconic hockey town where he launched his legend by leading his high school team to four state titles. Mayasich came to Minnesota and earned All-America honors three times while setting several records that still stand, including career points (298), career goals (144), single-game points (8) and single-game goals (6).

“The greatest Gopher of all time,” Motzko said.

Motzko called Mayasich.

“We’re coming up to see you, John.”

“Who’s we?”

“The whole team.”

Minnesota rerouted its trip and met Mayasich at the Eveleth Hippodrome, the 100-year-old rink where Mayasich and other former Gophers cut their teeth, including John Mariucci, whose name is on Minnesota’s arena.

“It was special to see him,” Faber said. “Obviously, he’s still such a huge supporter of us. We’re grateful to wear that ‘M,’ and to be able to be here, such a storied program with such great alums. There could be a little bit of nerves, knowing that all those guys are watching, but it feels like we have so many people behind us.”

The allegiances within the state are more divided now. There are too many good players and too many good Division I programs. But those who grow up in Minnesota and wear the Gophers’ jersey understand what’s at stake.

Of the 26 players on Minnesota’s roster, 20 are from the state.

“It’s everything,” said LaCombe, a native of Eden Prairie. “It’s the heartbeat of Minnesota, and everyone plays. Whatever soccer is in Europe and football is down South, that’s what it is up here for hockey.”

Motzko grew up in Austin, near the Minnesota-Iowa border, and has spent the past 22 years coaching in his home state. He led the program at St. Cloud State, his alma mater, from 2005 to 2018 before returning to the Gophers.

The 61-year-old is a hockey lifer, but the past two seasons have been different. In July 2021, Motzko’s 20-year-old son Mack was one of two passengers killed in a single-car accident in which the driver was drunk. Mack had been playing junior hockey.

“For what I’ve been through in my life, this [season] has been great,” Motzko said. “I’ve needed hockey more now than I’ve ever needed it.”

Motzko isn’t one to make big speeches about big goals. He prefers the “slow drip” approach to messaging, noting that the “boring coach” comes out when outlining the steps to success.

If Minnesota wins a title, Motzko believes it will be because the Gophers don’t take penalties, commit turnovers or go offsides. But he provides subtle reminders of the larger objective, like the final word on the dry-erase board in Minnesota’s team room before a recent skate: “LEGACY.”

“We’ve had a really good regular season and we’ve given ourselves a chance to win,” Snuggerud said. “We haven’t done so in 20 years and it’s our time. Hopefully, we can get the job done.”

Source: Read Full Article