‘Foolishness has a price’: Ronan, 17, thought he was messaging a potential girlfriend who’d asked him to share intimate photos. Disastrously, he agreed and suddenly the blackmail threats began… and it all ended in tragedy

- ‘Sextortion’ sees blackmailers target people who share intimate images digitally

- Cases of sextortion rose 40 per cent from 2020 to 2021 with mostly male victims

- Ronan Hughes, 17, from Co Tyrone, Northern Ireland, was blackmailed by a gang

- He went into a field and took his life, while the gang members were later jailed

Charles is in his early 30s, with a well-paid job in a large British city. He is affluent and internet-savvy — but he is also, like many men and women, naive and susceptible to flattery.

And this has cost him dear.

‘This week, I was a victim of cybercrime — specifically what I think is known as sextortion,’ he said. ‘A young and attractive woman, probably in her early 30s, sent me a message on Instagram telling me she lived nearby.

‘She invited me to sign into Telegram [an encrypted online chat platform, similar to WhatsApp] and chat. I was bored so I thought, why not.’

It proved to be a terrible mistake. Their conversation soon turned sexual. ‘Within a couple of hours, I had sent her an explicit video. She became even more friendly, telling me I was “hot” and asking for a picture of my face.

And, like an idiot, I obliged.

‘The men and women who have suffered sextortion say it can be even more devastating than blackmail. Part of the terror they feel comes from the fact they will never know the names of the perpetrators’

‘As soon as I did that, I got another message back — almost immediately, but this time it was from a man. He wanted £1,000 or he would send the video and pictures of my face to all my followers on Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. That would include my friends, my sisters and my nephews and nieces — and a lot of people from work.

‘I was terrified. I have deleted all my accounts. But the demands for money are becoming bigger and more insistent, the threats scarier.’

Now Carl is living a nightmare. ‘He has told me he will give me a bit more time to get the money together, but I have no idea how long this is going to last. I have talked to the police but since I don’t know who this person is, they say they just don’t have the resources to track him down. It’s a horrible crime and I still don’t know why I was so stupid as to fall for it.’

Carl is a victim of ‘sextortion’ — an insidious and growing crime, and one that is almost impossible to control.

As in his case, it typically starts with a brief online exchange between two strangers, usually through a social media site such as Snapchat or Instagram. The victim is soon pressured to send intimate photographs or videos of themselves to the person talking to them — often an attractive person of the opposite sex. Once the material has been sent, the sender is then blackmailed, often for sums running into the tens of thousands of pounds. It can end in tragedy.

In 2013, 17-year-old Danny Perry from Dunfermline threw himself to his death from the Forth Road Bridge. He had been duped into an explicit Skype chat with what he thought was a young woman: two Filipino men were later arrested in Manila for blackmailing him, but they have not been prosecuted

As the Mail’s recent investigations into the scale of fraud taking place in Britain have powerfully shown, these are crimes that haunt their victims for life.

The men and women who have suffered sextortion say it can be even more devastating than blackmail. Part of the terror they feel comes from the fact they will never know the names of the perpetrators, who are simply lurking in cyberspace, untraceable.

A new report published by the online safety charity SWGfL, which runs a helpline for victims of ‘revenge porn’ and receives financial help from the Government, says cases of sextortion now make up a quarter of the incidents of online harassment reported to the charity.

During the pandemic, between 2020 and 2021, the number of sextortion cases reported rose by more than 40 per cent — and 90 per cent of the victims were men.

Experts believe this is because people spent more time at home, often in isolation, and were sitting ducks for the criminals.

No doubt many people will take the view that if you are stupid enough to post compromising pictures of yourself online, you should be willing to face the consequences.

But many victims are young, naive and in some cases lonely and socially awkward. Often they are just looking for a girlfriend and are all too easily manipulated.

Another British victim has told his story on a U.S. website set up to help victims of sextortion. His account chimes with Carl’s.

‘I was chatting with what I thought was a girl via Snapchat, and she started following me on Instagram.’

After he had sent her sexual images, he said: ‘The messages took a turn. She created an Instagram group with a load of my friends and threatened to release pictures of me. She asked for £500, which I did initially pay … They then released the photos via the Instagram group anyway.’

Many of the victims of sextortion are similarly culpable. But the problem is becoming so severe it is almost impossible for the blackmailers to be brought to book.

And men aren’t the only victims — the women who persuade them to share their pictures are often victims themselves.

Coral Dando is a former Metropolitan Police detective who is now a professor of forensic psychology at the University of Westminster.

She told the Mail: ‘Many of these women have been trafficked into this kind of work. It’s very difficult to identify the gangs involved, but we know organised crime is behind a lot of this type of extortion.

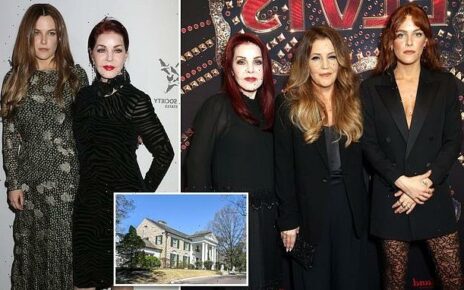

Ronan Hughes, from Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland, also took his own life in 2015 after he was targeted on Facebook by a gang based in Romania. They threatened to release pictures to his family unless he sent them £3,400 in Bitcoins

‘The gangsters are invisible but the women are not and could be key to getting people caught. They are victims of what is effectively modern slavery — and although some members of the public might believe male sextortion victims bring it on themselves, these women are innocent.’

The Revenge Porn helpline says it received 1,124 reports of sextortion in 2021 compared with 593 the year before. And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

‘Many people are simply too embarrassed to report sextortion because they think it reflects badly on them,’ says Zara Ward, who deals with sextortion victims every day. ‘They just pay up. And the platforms could do much more to warn people.’

Her charity’s latest report says that 65 per cent of those who report their experiences to the police are unhappy with the response.

But forces are stretched, and many units prioritise investigations into child pornography and grooming by paedophile gangs.

A spokesman for the National Crime Agency (NCA), which oversees the national response to online crime, told the Mail: ‘Sextortion is a crime that can cause substantial harm, both emotionally and financially. It is vital that victims report instances of it to their local police, who will deal with any allegations in a sensitive and confidential way.’

Frustrated by the apparent inability of the police to crack down on the sextortionists, some victims are making law firms their first port of call. David Sleight is a criminal litigation partner at top law firm Kingsley Napley in central London.

An expert in cybercrime, he has noticed a massive increase in the number of sextortion victims approaching his firm for advice, often in desperate straits.

‘They are embarrassed and often humiliated,’ he says. ‘They are frequently in a state of some anxiety, since they don’t know how their lives, marriages and careers will be affected at the hands of the blackmailers.

‘Blackmail is an awful crime because victims feel helpless and can’t control it. Unless, of course, you are willing to go to court. And not everyone is, for obvious reasons.’

Mr Sleight adds that victims of sextortion often pay up long before the police get involved. ‘In a blackmail or sextortion trial, there is no automatic right to anonymity for victims, unlike victims of rape. The grisly detail will be heard by everyone in court and potentially reported by the Press. That’s one reason so few sextortion cases end up in court.

‘The people who come to us are sometimes being asked for £5,000 or £10,000 by the blackmailers. Generally, they can afford to pay, but our advice is often to ignore the threats — and do nothing.

‘Sometimes the online extortionists are operating on such an industrial scale that they are putting out demands for money by the thousand . . . they are hoping that just a handful of victims will bite, and what they get from them will make it worth their while.’

Professor Roberta O’Malley of the University of Southern Florida is one of the world’s leading experts on this sordid crime.

‘It may start with a demand for £100, but it soon creeps up,’ she says. ‘We’ve also noticed among younger victims that there is an element of “bidding down”. If a teenager doesn’t have £1,000, the perpetrator might ask for £500 and they pay up. Then it starts again.’

Prof O’Malley is under no illusions about what motivates some of the victims. ‘They’re engaging in risky behaviour; they’re meeting other risky people,’ she says. ‘And these men are pleased they are finally getting reached out to by women on dating apps. ‘

The criminals know that and that’s why these communications can get so explicit so quickly. The victims don’t know they’re being blackmailed till it’s too late.’

Prof O’Malley believes social media platforms should do much more to warn users about the risk.

‘A lot of the platforms, such as Tinder, Grindr, Instagram and Snapchat are just ignoring it. The dating apps are probably the worst — they are already letting ads from sex workers appear without any sanction. No wonder they don’t seem interested in combating the blackmailers. Social media platforms know sextortion is going on, but unless someone complains to them about being a victim, they won’t do anything.’

Some cases of extortion have had tragic consequences. In 2013, 17-year-old Danny Perry from Dunfermline threw himself to his death from the Forth Road Bridge. He had been duped into an explicit Skype chat with what he thought was a young woman: two Filipino men were later arrested in Manila for blackmailing him, but they have not been prosecuted.

His mother, Nicola Perry, recalled at the time: ‘It was a female he was talking to. I believe they were talking for a few months and he believed he was talking to this American girl from Illinois.’

Another victim, John, fell prey to a similar crime. He told the BBC what happened to him. ‘I went on Facebook and she said: “Add me on Skype.” So I did and she then said: “Let’s do webcam and I’ll get naked for you.”’

Like so many others he allowed himself to be cajoled into appearing on video.

‘She said she’d tell my family and friends, tell my daughter, tell my wife — and ruin your life, ruin your family. I was very frightened — just the thought of them seeing that was really terrifying. ‘

I feel like telling everyone about it … it happens to a lot of people … Just the thought of your close family and friends seeing that video, it terrifies you.’

Ronan Hughes, from Co. Tyrone, Northern Ireland, also took his own life in 2015 after he was targeted on Facebook by a gang based in Romania.

They threatened to release pictures to his family unless he sent them £3,400 in Bitcoins.

He told them, just before his death: ‘I’m only 17, please, I’m begging you — don’t.’

The perpetrator replied: ‘That’s not my problem. Foolishness has a price. And you’ll pay.

‘Do you want to tell your mother or will I? You have 48 hours from now. Time is running out!’

Ronan was found dead in a field near his home. The extortionists were eventually caught in Romania and jailed for four years.

The Mail approached Meta, which also owns Instagram. Meta did not wish to comment on this case, but a spokesperson said that the company supports the use of StopNCII.org, a tool that helps end the non-consensual sharing of intimate images.

‘We’ve invested heavily in strengthening our technology to keep fake accounts off Facebook and Instagram,’ they added.

Although the authorities insist they are doing their best to combat sextortion, these gangs are operating outside Britain, mainly in the Philippines but also in Romania, Morocco and the Ivory Coast.

Any investigation abroad requires massive resources. And the problem is that the public often blames the victims themselves for falling to the perpetrators.

This can risk looking like a case of clear double standards. When an unwitting person, perhaps an older or more vulnerable individual, falls victim to financial scammers and loses their money, we feel sympathy for them.

But when a similarly unwitting person shares intimate pictures with someone whom they believe to be a willing partner, and is then blackmailed for them, often society takes the view that it’s their own stupid fault.

And whether we like it or not, millions of people — and probably a majority of younger people — do send intimate pictures of themselves to their partners.

Dr Calli Tzani, an investigative psychologist at Huddersfield University, told the Mail: ‘Of course, it’s common sense not to send intimate pictures to anyone. But sextortion has become such a problem that unless we do something about it, we may find more lives ruined, more suicides, more families devastated.

‘Is it right that so many innocent people should suffer from a single, simple mistake?’

- Carl’s account came via a third party involved in helping victims. His name was changed to protect his identity. Stop.NCII.org can be downloaded free of charge.

Source: Read Full Article