Farmers are taking major action to defend against a potential foot and mouth outbreak in Australia, including preparing genetic banks to one day repopulate their animals through IVF.

The disease is spreading through Indonesia and border authorities are desperately trying to keep it from entering Australia for the first time in 30 years. Only viral fragments have been found in food products so far.

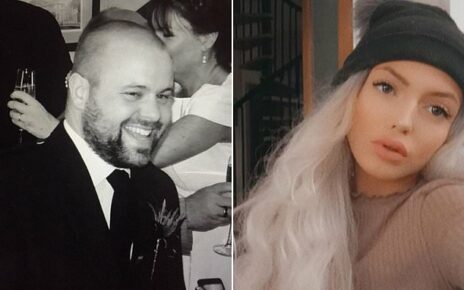

Sheep farmers Craig and Jenny Bradley are preparing against a foot and mouth outbreak in Armatree, near Dubbo.Credit:Nicole McGuire

A single reported case would halt the movement of surrounding livestock, force the culling of thousands of animals and shut down Australia’s $27 billion livestock export trade.

Farmer Fiona Aveyard is prepared for the worst. “It’s daunting because [foot and mouth] is something on a scale we haven’t seen. It’s like a drought or a bad flood. You take a deep breath. I’m thinking to myself, ‘Am I mentally ready for this?’”

“If foot and mouth gets here, things will shut down for a while,” she said. “It’s not just about farmers’ mental health, having to destroy their life’s work … for the everyday person there will be long-reaching consequences.”

Fiona Aveyard on her property near Dubbo.Credit:

New stock arrivals are regularly quarantined from other animals when they arrive at farms, but producers are now monitoring stock for any signs of sickness, including blisters appearing on mouths and feet, and animals drooling and collapsing.

She has already cancelled farm tours and is considering adding cleaning mats for essential contractors and trucks entering the property, too.

If foot and mouth is detected, farmers are required to kill all animals on the property. That risk has driven lamb and grain farmers Jenny and Craig Bradley, along with son Jack, to update their genetic banks in the event they need to start again.

The family’s farm in Armatree, just north of Dubbo, has sent a collection of their rams’ sperm to an artificial insemination centre to be preserved on dry ice. A farm’s genetic superiority, often created over multiple generations, is the lifeblood of any livestock business.

“They collect that semen [to be put into ewes] via in vitro fertilisation,” Jenny Bradley said. “It’s stored at a temperature where they can bring it out of storage and it comes back to life and still works.”

If their animals were culled, the family would attempt to buy back sheep they had previously sold to other farms. But she is concerned about how an outbreak would affect the mating season.

“We’ve got semen stored to use, but we’ve got no embryos because [the sheep] are breeding. It won’t be until next March that we’ll be able to collect embryos from our breeding stock. We invest a lot of money into our genetics,” she said.

“If anything was to happen, and they had to be destroyed before we get a chance to harvest embryos, we’d lose all those genetics in one fell swoop.”

Jenny said the coverage of the livestock felt dramatised. “But, we’ve never had it this close, and Bali is a very popular place to travel.”

“We’re pretty resilient in the bush,” she said. “Farmers tend to get on with their job and their business and cope as much as they can. But this will be a different level if it comes in.”

“We’ve got four really big overseas buyers who pay really well for a high-quality product. But if we get FMD our markets shut down for probably close to 12 months. Once the export markets open up, will we still have those big buyers, or will they have gone off somewhere to find another product?”

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article