Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Finally, science has confirmed what many of us have suspected for a long time: if you want to get something done, get angry about it. Anger is often derided as fruitless and self-destructive, and more positive emotions promoted as conducive to wellness, but research published this week finds, by alerting people to “important situations that require actions”, unleashing anger can help “overcome an obstacle”.

The study, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, consisted of a series of experiments with more than a thousand people, invoking emotions in them, such as anger, amusement, desire or sadness, then presenting them with a challenging goal. And the angry ones got stuff done! (And, just quietly, in one experiment, cheated more.) This was especially the case when the tasks were harder.

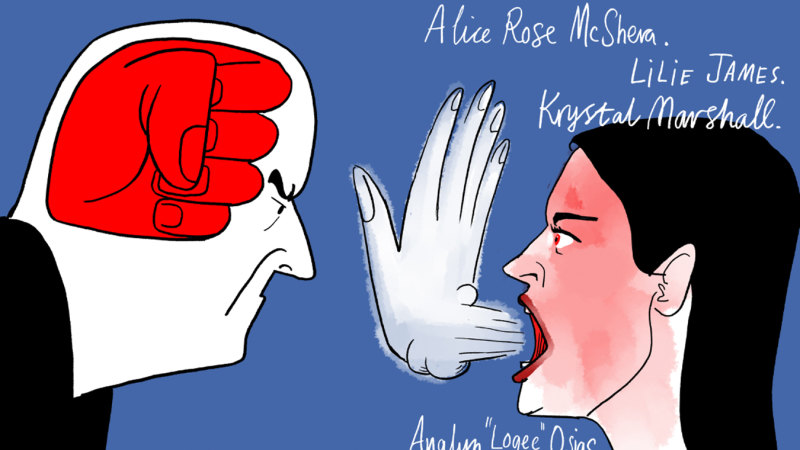

Illustration: Simon Letch Credit:

The researchers also analysed data from the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections and found that people who said they would be the angriest if their candidate did not win were the most likely to vote, even though anger had no bearing on their choice of candidate.

Lead author Heather Lench, a professor in psychological and brain sciences, concluded that the research showed “anger increases effort toward attaining a desired goal, frequently resulting in greater success”.

Which brings me to violence against women. Both outrageous and regular, shocking and commonplace. Are we angry enough about this? Why do we accept it as part of life?

Just last month, five women allegedly killed by male violence in 10 days. A 34-year-old lawyer found in a fancy hotel room in Perth, her head smashed in by what police called “a blunt instrument”. A 21-year-old sports coach, found in a toilet cubicle at Sydney’s St Andrew’s Cathedral School, her head beaten by a hammer. A 46-year-old mother found in an apartment in Bendigo, dying in front of two of her young children. A 38-year-old South Australian mother found burnt to death in her blackened Adelaide home. A 60-year-old Canberra woman stabbed to death in her kitchen.

Men have been arrested and charged in all but the Sydney case, and their matters are now before the courts. We can’t presume the outcome of the judicial process, where charges need to be proven beyond reasonable doubt. But entirely separate to these fatalities, a mounting toll of violence and death in recent years has left women wondering where, exactly, they can be safe.

Where, exactly, are women safe? Not the streets, not their homes, not their workplaces. Their lifeless bodies spot the country, red pins on a map, ever moving, always there.

Will we remember these names next month? Alice Rose McShera. Lilie James. Analyn “Logee” Osias. Krystal Marshall. Thi Thuy Huong Nguyen.

Forty-three killed this year, according to Counting Dead Women Australia, run by Destroy the Joint.

I was thinking about anger this week because of an Instagram reel by @AngryBodies – “a music performance project that celebrates emancipating power of anger” – that made me laugh. Two women, dancing with jerking authority, chanting: “FRUSTRATED MAN IN POLITICS – TAKE SOME F—ING THERAPY! ANGRY WOMAN IN THERAPY – ENGAGE YOURSELF IN POLITICS!”

Women so often blame ourselves for our sadness, instead of tearing apart the systems that enable abuse and violence to continue, with bare hands and raw rage. I mean, what makes a man kill a woman he can’t have? Who won’t love him, won’t be controlled by him, won’t submit to him? Entitlement, carelessness, opportunity? No reason can be enough.

Every time this happens, we tsk, scan gruesome stories, feel bad, click to the next article.

We all agree that this is bad, but do we agree on its urgency, priority and prevalence? We must get angry about every single case, every woman lost, every one. We must get angry about the ignorance and denial: the National Community Attitudes Survey, conducted by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women, found nine in 10 Australians think violence against women is a problem, but only half think it happens in their own suburbs. One in 10 thinks men should have control in relationships.

We must get angry about misinformation – the same study found four in 10 Australians think that men and women are equally likely to be violent against an intimate partner. Four in 10 also believe women exaggerate abuse to better former partners in custody disputes.

All wrong.

People roll their eyes when the phrase “believe women” is aired, for fear it implies an assumption of guilt, when in fact it means that the claims of women should be investigated, interrogated, taken seriously. It means we should not begin with the premise, or posture, of disbelief.

We must get angry when women are automatically disbelieved, discredited, shut out of a system that has long denied them justice. When so few perpetrators are convicted that, as Chanel Contos argued in her address to the National Press Club this week, we have effectively decriminalised sexual assault in this country.

Yet female anger has been pathologised for centuries.

In January 1971, doubtless feeling the scorching heat of the second-wave women’s movement, a Mr Nathan K Rickles wrote a piece in Arch Gen Psychiatry, warning of something fearful called “The Angry Woman Syndrome”. The symptoms, he said, included: “periodic outbursts of unprovoked anger, marital maladjustment … a morbidly oriented critical attitude to people”. Case studies were provided of these women, along with “their suffering male counterparts”, with Rickles concluding that treatment, unsurprisingly, was “usually resisted”.

You can only hope those “angry women” who resisted Mr Rickles attempt at treatment turned their attention from therapy to politics, from sedatives to sedition.

Professor Kate Fitz-Gibbon, director of the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, says while the government’s unprecedented funding commitment of $2.3 billion over this and last year’s budgets to address women’s safety “sounds impressive, it is not commensurate with the scale of the crisis of domestic, family and sexual violence in Australia”. She says there is urgent need for “increased funding to accelerate delivery of these action plans”. Crucially, some of these actions may not work; they need to be monitored for effectiveness.

We need to hold our politicians to account. Measuring outcomes. Recognising how many of these deaths are preventable. Imagine reading the legacy pieces of a premier or prime minister: “Twenty per cent drop in the number of women killed as a consequence of her policies”.

What I am arguing for is urgency.

It should be part of every political interview. Included in metrics of success for state and federal politicians should be reducing the number of women killed, beaten and abused by men who profess to love them. We should remind each other of the women we have lost, remember their names, think of how different the world might be if women were not in danger of dying in their own workplaces and homes, their bedrooms, bathrooms and kitchens.

Julia Baird is a journalist and author. She hosts The Drum on ABC TV. Her latest book is Bright Shining: how grace changes everything.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article