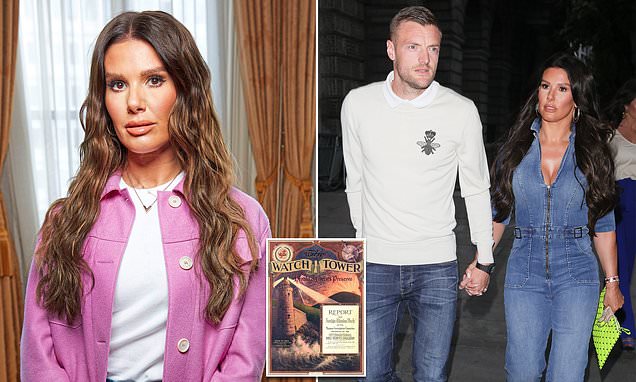

‘I was sexually abused aged 12… the church hushed it up so I didn’t bring shame on my family. They can’t silence me any longer’: WAG Rebecca Vardy reveals the trauma of growing up a Jehovah’s Witness – and why she now brands it a ‘dangerous cult’

In Rebekah Vardy’s childhood home there were no birthdays or Christmases, television and books were censored and she was warned that youthful mischief or bad manners would bring down the wrath of God on her. As a Jehovah’s Witness, she could not invite other children back to play, or sing hymns in her school assembly. Modesty was practised to the extent that she went through puberty without being told how her own body worked.

Her life and that of her extended family was governed by all-powerful ‘elders’ who sat in judgment with the right to cast people out of their closed community. Such was the dread of these men that when Rebekah told her mother she had been sexually abused from the age of 12, it was hushed up – for fear, she believes, of bringing shame on the family.

Now the WAG – the wife of Leicester City star Jamie Vardy, and a mother of five – is revealing this extraordinary and painful part of her past in a Channel 4 documentary. The 41-year-old is taking the role of reporter in front of the camera, interviewing other former Jehovah’s Witnesses and attempting to confront the movement at their £150 million UK headquarters in Essex.

‘I call it a cult,’ she says, speaking exclusively to The Mail on Sunday. ‘People are manipulated, brainwashed, it’s coercive behaviour and it is handed down from generation to generation. Once you’re in it, it’s so hard to see the bigger picture, which is that it’s wrong and immoral.

‘I spent my childhood fearful, being told we were going to die in Armageddon if we didn’t pray enough. I felt I had to constantly strive for perfection so that God would not be angry with me.

‘I spent my childhood fearful, being told we were going to die in Armageddon if we didn’t pray enough’

‘Jehovah’s Witnesses call someone who’s not a Witness a ‘worldly person’. I am the worst kind of worldly person because I have had the courage – along with all the people brave enough to talk to me for my documentary – to speak out against this religion and say it’s dangerous.’

The programme, which airs on Tuesday, is Rebekah’s first foray into the public eye since last year’s ‘Wagatha Christie’ High Court libel case. She sued Coleen Rooney after her fellow WAG accused her of leaking secrets from Coleen’s private Instagram account, which she denied. But the court found that Coleen’s statements were ‘substantially true’, leaving Rebekah with a legal bill estimated at £3 million.

The affair was turned into a sell-out stage play, a TV drama and a two-part documentary and it’s hard to reconcile the glamorous WAG at the heart of it with the lost and lonely little girl depicted in this documentary.

‘You never know what is going on behind the closed doors of a Witness house,’ says Rebekah. ‘It still fascinates me and it’s one of the reasons I wanted to make the programme. The other was the opportunity to explore the unanswered questions I had from my own childhood.’

Her formative years consisted of ‘Bible studies and knocking on people’s doors’, as preaching house-to-house is demanded of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

She says: ‘I was petrified, I cannot begin to tell you how traumatic it was when we met up on a Saturday, knowing we were going to be given our service rounds, thinking I might have to knock on the door of someone who was in my class. At school we used to get dragged out of assembly because we couldn’t sing the hymns or be present for any reference to religion, to Christian beliefs. If it was someone’s birthday, and everyone was singing ‘Happy Birthday to You’, that was the same, we had to leave. It was humiliating. Mortifying.’ Home life was also a minefield. Since Rebekah had not been allowed to learn the facts of life she was terrified when she started her periods and hid her underwear. ‘I thought there was something wrong with me, that I was disgusting, that I’d done something wrong.’

And if a character swore on TV, the set would be turned off instantly, with Rebekah believing she would have to pray harder that night to appease God. She says: ‘When I hear that sort of thing coming out of my mouth today, I think,’what a world…’ I don’t think you ever recover from it.’

At the age of 11 she felt the full force of the elders’ control over her family. Her mother suddenly fled the Jehovah’s Witness community in their home town of Norwich, taking Rebekah to live in Reading then Oxfordshire. Three decades later Rebekah still doesn’t know precisely why her mother upped sticks, but believes she may have had an affair. At some point her mother came to be disfellowshipped (expelled) by the sect and shunned by her fellow Witnesses.

‘I told my mum about the abuse that I was experiencing, and she cried. But she didn’t believe me’

In Oxfordshire, Rebekah was abused by a man known to the family, but not a Jehovah’s Witness, over a span of three years. She confided in her mother who turned to a Witness elder for guidance.

It was suggested to Rebekah she had merely ‘misinterpreted’ affectionate touching.

She says in the documentary: ‘What happened to me during my childhood still affects me every single day. From the age of around 12 years old, I was being abused. And instead of being supported, I was blamed, manipulated into believing it wasn’t the best thing to take it to the police.

‘I told my mum about the abuse that I was experiencing, and she cried. But she didn’t believe me. She told numerous members of the Jehovah’s Witness community.’

By this time Rebekah was a teenager, and the group called a meeting where ‘it was put to me I’d misinterpreted [as] abuse a form of affection. I knew that I hadn’t. I was well aware of what was right and what was wrong. And it was explained that I could potentially bring shame on my family.’

She says she was ‘basically manipulated into believing it wasn’t the best thing to do to take it any further and take it to the police. The impact on me was wild.’

‘I just blamed myself,’ she tells The Mail on Sunday. ‘I felt I hadn’t been good enough, I deserved it. It all goes back to that childhood pattern of seeking perfection.’

In the documentary she tracks down four similar cases. Waiving her right to anonymity and speaking on camera for the first time, a Northern Irish woman who was a Witness for half a century reveals how she was abused by an adult member of her congregation from the age of eight. But three pleas to elders went unanswered. It was as if the abuser ‘stole my life’, the survivor told Rebekah, explaining how she was the one who was punished by her old Witness congregation.

Eventually, in adulthood, she went to the police herself. Her abuser finally confessed on the first day of his trial and was given a suspended sentence.

The encounter between the two women makes compelling viewing. Rebekah remembers: ‘I had an almost out-of-body experience when she was talking – I was hearing her words but it was like I wasn’t in the room any more. It resonated with me so deeply. It was like I was listening to myself in ten or 15 years’ time.’

The psychological harm done to Rebekah by the decision to ignore the abuse was extensive. She attempted suicide at the age of 14, then spun into full teenage rebellion. She was made homeless after a family row at the age of 15 and ended up sofa-surfing until a job collecting glasses in a pub earned her enough money to rent a room in a bed and breakfast.

She met striker Jamie Vardy when she was hired to plan his 27th birthday party. They wed in 2016. For the sake of the documentary she left the Lincolnshire farmhouse they share with their blended family aged 18, 13, eight, six and three, and returned to Norwich for the first time in ten years. She revisited her former Kingdom Hall – the Witness equivalent of a church – which she attended twice weekly for Bible studies and worship. Much of her extended family remain in the area and are still part of the organisation.

She has not reconciled with most of them, including her mother to whom she has not spoken for seven years. ‘I’m at peace with that,’ she says. ‘You can’t dwell on the past. I’m not sympathetic towards her but I have an understanding – and because of that there’s no bitterness. I’d hate to carry anger and resentment forward, I’d be scared of passing those traits on to my own children.’

There are more than eight million Jehovah’s Witnesses worldwide and 130,000 in the UK, using their glossy magazine The Watchtower and online videos to promote their message

She does not know if her mother is still a Witness, but her father has left, as has her sister. And her half-brother was never part of the organisation.

There are more than eight million Jehovah’s Witnesses worldwide and 130,000 in the UK, using their glossy magazine The Watchtower and online videos to promote their message. The religion was founded in the 1870s by American preacher Charles Taze Russell on Christian principles, although it diverges from mainstream Christian churches.

Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that at the End of Days those who strive for goodness will inhabit a paradise on Earth. In pursuit of goodness, they operate a strict moral code which rules out adultery, smoking, drinking, homosexuality, gluttony, and swearing.

Most famously, they are banned from having blood transfusions.

In recent years the global organisation has faced questions about how it handles allegations of child sex abuse and its child protection practices.

In Australia, there have been public allegations of a cover-up. In the UK, the independent inquiry into child sex abuse across Britain’s leading institutions referred in its findings last year to a Jehovah’s Witness abused by a family member being discouraged from going to the police by a Jehovah’s Witness social worker who told her: ‘You know how Jehovah feels about liars.’

Rebekah digs into these controversies with the help of one former Witness who has spent a decade collecting evidence against the organisation after he was disfellowshipped for having sex before marriage.

She meets a woman interrogated by elders in front of her husband after she had an affair and was publicly shamed, and a mother whose Witness son killed himself after he was shunned for smoking.

Fascinatingly, she also tracks down two former elders, one with two daughters who were disfellowshipped. She believes it’s this fear of losing your family and friends and community which keeps so many Witnesses inside the sect.

She says she no longer fears it, but her emotional response to receiving a promotional letter from the Jehovah’s Witnesses suggests she still feels a sense of threat. ‘I was standing in my kitchen looking at this letter feeling absolutely amazed at the audacity of it crossing the threshold into my house, to think it was OK to have a conversation with me uninvited… it shouldn’t be allowed.’

She was reminded of the day a man threw hot coffee over her when she was a child going door-to-door because he was so enraged by the intrusion.

But she has taken her anger at what she calls her ‘ruined childhood’ and used it to create the opposite environment for her own brood.

Rebekah digs into these controversies with the help of one former Witness who has spent a decade collecting evidence against the organisation after he was disfellowshipped for having sex before marriage

Christmas in the Vardy house sounds quite something. ‘It’s like Santa’s Grotto.

‘I give them everything I never had – loads of Christmas trees, cookies, I even made a gingerbread train last year. It was like a glitter explosion in my kitchen.

‘We do Santa’s footprints and Elf On The Shelf. Jamie’s always asking what’s going to appear – are we getting inflatable reindeer on the roof? He knows Christmas is coming because I have gone off to the local garden centre.’

Birthdays are a riot of paper plates, balloon and fun gifts too. ‘What happened to me forms part of my resilience,’ Rebekah says. ‘And I think it makes me a better parent because I know exactly what I want to be for my children – and what I don’t want to be.’

The Jehovah’s Witnesses did not respond to The Mail on Sunday’s request for comment, but they told Channel 4 that elders are directed to immediately report an allegation of child sexual abuse to the authorities even if there is only one complainant. They also said it is ‘false and offensive’ to imply that they stand in the way of the authorities,

They rejected the suggestion that being expelled from the religion contributed to suicide and added: ‘Courts have rejected the allegation that disfellowshipping and so-called shunning results in social isolation and discrimination.

‘And it is simply misleading and discriminatory to imply that our religion is controlling.’

However they said they lacked the information to comment on individual cases.

For her part, Rebekah is adamant she did not make the documentary to change people’s perceptions of her following the Wagatha Christie case – though it will certainly do that. ‘I did it to raise awareness for other people, she says.

‘To say, look if I’ve been through this, then you can come out the other end with your head held high. I think it will help so many people that have been, or are still are, in this situation, desperately trying to get out.’

The closing scene is of Rebekah in a cosy restaurant having Christmas dinner with a table full of strangers who, like her, are former Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The woman with the WAG lifestyle and wardrobe to match is wearing a paper crown she’s got out of a cracker and frankly, she couldn’t look happier.

Source: Read Full Article