Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Key points

- A fossil discovered in a retaining wall by a retired chicken farmer has been formally identified.

- The fossilised creature is a newly described carnivorous amphibian that lived 240 million years ago.

- The two-metre creature looked like a salamander but probably acted more like a crocodile.

- The palaeontologist who analysed the creature’s bones first saw the fossil as a 12-year-old in 1997.

- He called it Arenaepeton supinatus, which translates from Latin to “supine sand creeper”.

A spectacular fossil discovered by a retired chicken farmer has been identified by palaeontologists as a new type of Triassic amphibian that stalked the freshwater streams of the Sydney basin 240 million years ago.

Mihail Mihailidis had purchased the 1.6-tonne sandstone slab for a retaining wall in his Umina Beach garden on the Central Coast, south of Gosford, nearly 30 years ago.

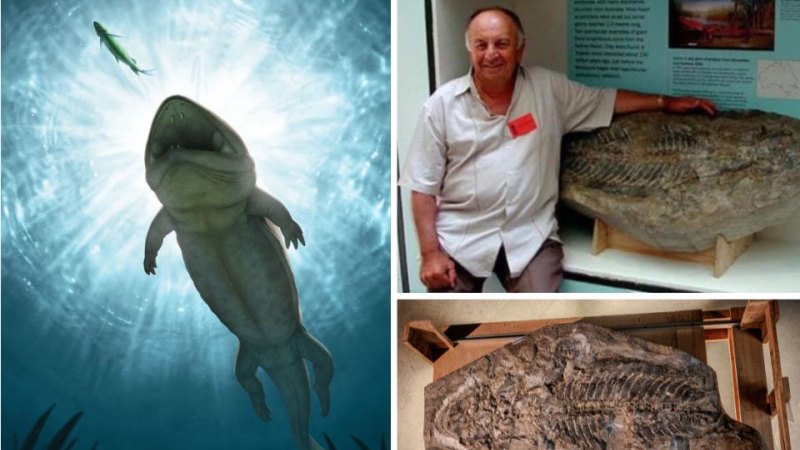

An artist’s recreation of the “supine sand creeper”, Mihail Mihailidis pictured in 1997 with the fossil he discovered, and the fossil today.Credit: José Vitor Silva, Alex Ritchie and Brook Mitchell

As the stone was hosed down, the dirt sluiced away and something extraordinary appeared: the mineralised remains of a 1.5 metre-long creature that pre-dated even the dinosaurs.

Mihailidis had made one of Australia’s most exceptional fossil discoveries. The find caused an international sensation, with much made of its finder’s past as a chicken farmer. Time magazine proclaimed: “Chance discovery of a fossil older than the dinosaurs may amplify the story of human evolution”.

An exhibition visiting Sydney from Canada in 1997, the Dinosaur World Tour, leapt on the fossil and unveiled it to an astonished public in Darling Harbour.

An ongoing question, however, remained about the fossil, which came to lie in a climate-controlled room at the Australian Museum for a quarter of a century: what exactly was this creature immortalised in sandstone?

Paleontologist Lachlan Hart with the fossil he and other researchers have now formally described and named.Credit: Brook Mitchell

Palaeontologist Lachlan Hart has finally solved that decades-long mystery and formally described the prehistoric creature in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. By chance, Hart first visited the fossil at the exhibition as a dinosaur-obsessed 12-year-old in 1997.

“My parents took me because I was obviously in love with dinosaurs and paleontology from a young age,” Hart, now a PhD candidate at UNSW, recalled. “Twenty-something years later, it’s become part of my PhD.”

Hart and his colleagues have identified the animal as a previously undescribed species of temnospondyl, an order of ancient carnivorous amphibian. The scientists formally named the creature Arenaepeton supinatus, which translates from Latin to “supine sand creeper”.

Almost the entire body of the sand creeper, besides its tail and back legs, was preserved. Even some of the animal’s soft tissue fossilised, denoting the outline of its salamander-shaped body and hinting at the possibility of prehistoric webbed feet.

“It’s incredibly rare worldwide to find what we call an articulated skeleton, when the head and the body are both attached,” Hart said. “An articulated skeleton plus soft tissue remains is almost, like, unheard of.”

The researchers observed two pits in the top of the sand creeper’s head, which once held a pair of tusk-like fangs. The creeper’s jaw was also ringed with tiny, sharp teeth that helped the predator latch onto its slippery aquatic prey.

“Even though they were more closely related to salamanders and frogs, they probably lived a lifestyle that’s more akin to crocodiles,” Hart said. “They would have been swimming around actively in the water pursuing prey.”

The temnospondyls were hardcore survivalists. They endured two of the earth’s five mass extinction events, including the deadliest ever event at the end of the Permian period, when a series of catastrophic volcanic eruptions annihilated between 70 and 80 per cent of species on earth and ushered in the age of the dinosaurs.

“Generally, when there’s a mass extinction and prey species become extinct, predators that specialise in one particular type of prey are the ones that are going to become extinct first,” Hart said. “And so, in the case of temnospondyls, perhaps they just weren’t very picky.”

The sand creeper also may have shared the ability to aestivate, a type of hibernation.

“There’s some frogs in Africa that can bury themselves in mud for six months at a time and stay alive. That’s within the temnospondyl lineage. There’s a possibility temnospondyls could have burrowed under the ground and just slipped through very inhospitable times in Earth’s history.“

The fossil will go on display at the museum later this year. At the time of its discovery, Mihailidis intended to sell the fossil to the highest bidder. According to Time he expected a million dollars for the slab.

Then-premier Bob Carr considered stepping in to purchase the fossil, but the Australian Museum’s senior palaeontologist, Dr Alex Ritchie, convinced Mihailidis to donate his discovery to the museum, where it has waited ever since for identification.

Hart has attempted to contact Mihailidis’ family unsuccessfully about the latest iteration in this discovery.

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article