TOM LEONARD: When Sister Wilhelmina was exhumed after four years, it sparked near hysteria… Following days of mystery, what IS the truth about the perfectly preserved nun who’s convincing many Americans that miracles ARE real

Sister Wilhelmina’s simple wooden coffin, handmade by a priest, had been buried for four years in a corner of her abbey’s land in Missouri’s farming country.

When her fellow nuns came with spade and pickaxe to dig up her body, they found the clay soil waterlogged and a crack down the middle of the coffin.

As they slid open the lid to flash a torch inside, Abbess Cecilia let out a scream. Instead of a pile of crumbling bones, she glimpsed a perfectly intact foot.

And it wasn’t just the foot. All of Sister Wilhelmina was there, her body — which the nuns insist hadn’t been embalmed or preserved — showing almost no signs of decomposition.

Wilhelmina had died aged 95 in 2019 and anxious to reinter at least some of the remains of their founding abbess in a new altar in their chapel, the nuns made their astonishing discovery in April.

All of Sister Wilhelmina was there, her body — which the nuns insist hadn’t been embalmed or preserved — showing almost no signs of decomposition

Wilhelmina had died aged 95 in 2019 and anxious to reinter at least some of the remains of their founding abbess in a new altar in their chapel, the nuns made their astonishing discovery in April

READ MORE: She had a vision of Jesus at 10 – and survived a knife attack thanks to her homemade habit: Incredible life of Sister Wilhelmina, whose ‘perfectly preserved’ remains – exhumed four years after her death – are being hailed a miracle

Even her nun’s habit was ‘perfectly preserved’, say the Benedictine nuns of Mary, Queen of Apostles, who had been warned, given Missouri’s baking summers and freezing winters, not to expect that much of Wilhelmina would be left.

Skeletal remains typically weigh around 20lb but Wilhelmina’s were reportedly between 80 and 90lb. ‘I thought I saw a completely full, intact foot and I said, ‘I didn’t just see that,’ said Abbess Cecilia. ‘So, I looked again more carefully.’

The nuns cheered when she confirmed she hadn’t imagined it. ‘There was just this sense that the Lord was doing this.’

Bodies that do not decompose are known as ‘incorrupt’ in Catholicism and based on the belief that it’s a result of divine intervention, Church authorities view it as a sign of holiness and a possible first step on the way to sainthood.

That ‘first step’ alone is enough for the thousands of people who have been making a pilgrimage to the order’s abbey in Gower, Missouri — to see and even touch Wilhelmina’s body.

Up to 500 pilgrims an hour have filed past her remains, say volunteers. They were allowed to touch her hands and face before her body was moved into a glass case.

So desperate have the hordes been for relics connected to the wondrous Wilhelmina that a sign has been put up by the grave that once held her — now blighted by two big holes — which pleads: ‘Please take no more than a spoon of dirt.’

The believers still queue outside the nuns’ chapel for the chance to kneel before the flower-covered shrine containing Sister Wilhelmina, whispering prayers and touching rosaries and crucifixes to the glass.

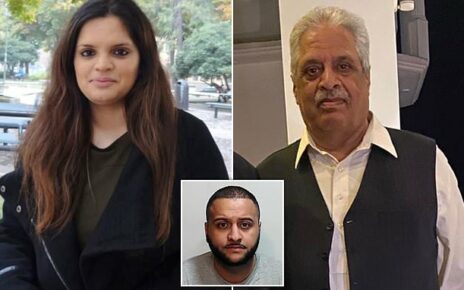

Pictured: After many years of writing to Pop St. John Paul II, Sister Wilhelmina finally met him in 1998

READ MORE: The miracle of Missouri: Thousands of Catholics flock to church to pray over body of nun who was exhumed after four years but showed NO signs of decay – as they call for her to be made a saint

She is far from being declared a saint yet, but those flocking to see her believe it’s only a matter of time. ‘This sort of thing you usually have to go to Rome for,’ said Becky Hund, an overjoyed lay volunteer at the abbey.

Many felt the same way, sharing her delight and wonder that a workaday, tractors-and-trailer-parks corner of the American Midwest might have produced its very own saint-in-waiting.

Indeed, emotions have run so high that during morning Mass on Thursday, just as a bell rang during the consecration of the bread and wine, a woman in the congregation suddenly — and inexplicably — screamed at the top of her lungs before being gently led outside where she sat shell-shocked on some steps.

John and Patty Zarybnicky had driven two-and-a-half hours from Odell, Nebraska, bringing their 32-year-old daughter, Emily, an occupational therapist, and a pair of rosaries they pressed dutifully to the glass of Wilhelmina’s cabinet.

Were they hoping it will imbue them with something? ‘It doesn’t matter,’ said John, who works in property. ‘Nobody knows what this all will evolve into but we’re here at Ground Zero.’ His wife, a retired lab technician, added: ‘I guess I want to hope we’ll have another saint in our midst.’

It was quite difficult to see what we had in our midst. Wilhelmina’s new home in a poorly-lit corner of the chapel offers little chance — unless you’re prepared to do anything as unforgivably irreligious as shine a torch — of checking just how incorruptible her body really is.

But the pictures before she was enshrined speak for themselves. While her face and wizened hands are all that is visible of her skin, she doesn’t look anything like as old as 95, but nor does she look like she’s been dead and buried for four years.

The local Catholic diocese warned the faithful that it was important to ‘protect the integrity of her remains . . . to allow for a thorough investigation’. It added: ‘Incorruptibility has been verified in the past, but it is very rare.’ Indeed, the Catholic Church has only ever recognised the existence of a little over 100 incorruptible saints. The nuns acknowledge that Wilhelmina has not yet been dead for five years, the minimum that must elapse before the sainthood process can begin. Candidates for sainthood must also be shown to have lived a life of ‘heroic virtue’.

Skeletal remains typically weigh around 20lb but Wilhelmina’s were reportedly between 80 and 90lb

Wilhelmina grew up in a poor but devout African-American family in St Louis and reportedly wanted to serve God from the age of nine. She applied to join an order of nuns when she was 13 but had to wait until she’d finished school.

An ecclesiastical conservative, Wilhelmina rebelled against the Vatican when it swept away the nun’s full habit.

When the sisters stopped wearing the full traditional headdress, she made her own, fashioning parts from a white bleach bottle. It reportedly saved her life when it deflected a knife thrown at her by an angry student when she was teaching in Baltimore.

But to have a serious chance of sainthood, Wilhelmina needs some miracles, which may already be in hand. According to Ms Hund, some who’d visited her body had already reported experiencing miraculous recoveries. ‘I don’t know what they are but they’ve been in communication with the sisters. It will have to be validated,’ she said.

‘We’ve had people here with stage four cancer and brain tumours. They wanted to touch her. Maybe they were in search of a miracle and maybe what they received was peace.’

After making an initial statement, the nuns have stopped talking publicly about Wilhelmina and, according to their lay helpers, feel slightly fazed if curious about all the attention.

The 43 nuns at the abbey are not, however, entirely new to the spotlight. The small, contemplative order (meaning they are devoted to prayer rather than works), founded by Sister Wilhelmina in 1995, is usually deeply private. Apart from the occasional doctor’s appointment, its generally young sisters rarely venture outside their gates.

They keep their own cows and grow their own vegetables on their 100-acre estate. But — rather more surprisingly — they’ve developed a highly fruitful sideline as successful recording artists.

Wilhelmina grew up in a poor but devout African-American family in St Louis and reportedly wanted to serve God from the age of nine

The sisters, who reportedly sing for five hours a day as part of their life of prayer, have so far released ten albums of chants and hymns, the first two of which reached No.1 in the Billboard charts for classical or traditional music. In 2012 and 2013, they became the first nuns to be named Billboard magazine’s classical traditional artist of the year, beating stars such as Sarah Brightman and Andrea Bocelli.

Despite this secular world fame, the sisters insist they never sought the blizzard of attention they’ve received over Sister Wilhelmina. (One of their friends in the lay community gave it away after sharing the details of an email the nuns had sent to a few people).

But already notes of scepticism are making themselves heard: according to dissenters, Sister Wilhelmina’s striking physical conditional may not be quite so remarkable as is being assumed.

Some experts have pointed out that, given people are rarely exhumed after just four years, we have little evidence on which to base our assumptions on what they should look like by then. Rebecca George, a forensic anthropologist at Western Carolina University, believes that a lack of moisture and oxygen in a coffin, combined with clay soil keeping the temperature low, can start a process of mummifying the body rather than breaking it down.

Heather Garvin, a forensic anthropologist at Des Moines University, said an airtight coffin (bacteria that break down the body need oxygen) and climate are among the many variables that affect decomposition rates.

But, after looking at pictures of Wilhelmina’s body, she said she thought her hands had mummified. She also saw a shine on them, and without going so far as to accuse the nuns of fibbing, she said it ‘makes me wonder whether anything was applied’.

The nuns say they did apply wax to her exposed skin after she was exhumed, but only to moisturise and protect it from the touch of so many visitors.

Another theory, by a mortician, is that the body was preserved by ‘grave wax’, a soap-like fatty tissue that can encase a corpse or parts of it and stops decomposition. It is caused by water and alkaline soil getting into the coffin and turning body fats into soap.

The sisters insist they never sought the blizzard of attention they’ve received over Sister Wilhelmina

Yet few of the people I found waiting to commune with Wilhelmina cared what science had to say. ‘This isn’t about science, it’s about faith,’ said Trizah Macharia, who’d driven 13 hours from Georgia. ‘Science thinks it can explain everything, but this is a miracle.’

While some instinctively agreed with her, others admitted they didn’t know what to make of it.

‘I’m kind of amazed,’ said retired factory worker Dennis Frederick who’d travelled five hours from Illinois with his wife. ‘It’s not like it’s changed my faith, which has always been deep. It’s just a sign that God can do whatever He wants. That He’s just still around in these ugly times we’re going through.’

Sara Butta, a 51-year-old nursing home assistant who’d driven 900 miles from San Antonio, Texas, with her fiance, agreed it somehow held a message for the U.S. to ‘come back to God’.

Dan Girolametto, a telecoms executive from Kansas, wasn’t sure if it was a miracle, but added: ‘I don’t know what a four-year-old corpse should look like either — but I can tell you that’s not it!’

Which devout Catholic wouldn’t rejoice in finding evidence that God moves in mysterious ways.

But will their fellow Americans look at an uncannily well-preserved nun and see the hand of God — or a natural marvel with a rather more scientific explanation?

Source: Read Full Article