Was this playboy jockey who dated Pamella Bordes tortured and murdered by a British drug gang, as his son fears?

- Barrie Wright was held ransom to settle a large debt reportedly owed for years

- Since 2020, his story has remained secret to all but police, family and friends

The ultimatum was sent from a heavily encrypted mobile phone, the sort of device used only by Europe’s most professional organised criminals.

Barrie Wright, then 64, a sometime London society playboy and jockey, was being held to ransom to settle a hefty debt which his kidnapper claimed to have been owed for years. If the money was paid quickly, in cash, he would be freed unharmed. If it wasn’t, the consequences didn’t need to be spelled out, encrypted or not.

Related to me by Wright’s son Tommy, 22, this was the nerve-shredding endgame in an underworld joust played out, in February 2020, in the backwaters of Belgium.

For three years, the story behind the British rider’s sudden disappearance has remained a closely guarded secret known only to the Antwerp police, his family and a close circle of friends.

But now, with Wright still missing — presumed to have been murdered — and the Belgian authorities preparing to close the case for lack of evidence, Tommy Wright has decided his father’s story must be told. By speaking out, he hopes someone might come forward with vital evidence to trap his ruthless abductor and probable killer.

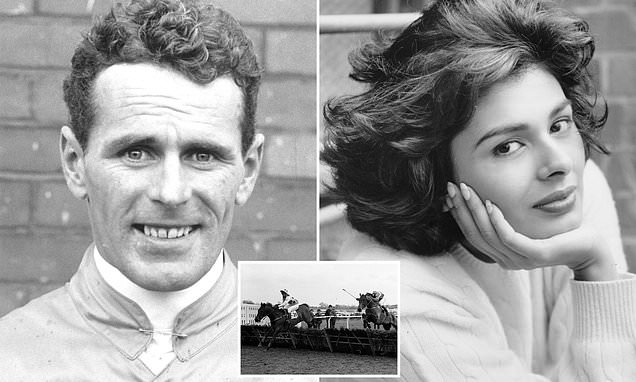

Barrie Wright, a sometime London society playboy and jockey held ransom over owed debts

Pamella Bordes, an alluring, £5,000-a-weekend society call girl branded ‘the new Christine Keeler’

Looking back at Wright’s chequered past, it’s easy to conclude he had been riding for a fall for many years.

He was hardly a star name in the saddle, but he hit the headlines in 1989 when he was revealed to have been among the many lovers of former Miss India, Pamella Bordes, an alluring, £5,000-a-weekend society call girl branded ‘the new Christine Keeler’.

Bordes was feared to have compromised national security by working as an MP’s assistant in the House of Commons and dating Sports Minister Colin Moynihan while also sleeping with a cousin of Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi and other potential state enemies.

But as the Sunday People luridly revealed, Barrie Wright was her ‘bit of rough’.

‘Posh Pam Gave Me My Oats’, the paper leered, describing how the brazen Bordes told Wright she planned to become his lover just moments after they first met at her birthday party in Tramp, the London nightclub then favoured by celebrities and politicians.

Full of equestrian puns, the story claimed Wright had then spent an exhausting fortnight in the femme fatale’s clutches but bolted when she suggested marriage. In his autobiography, Wright’s friend, champion jockey Graham Bradley, who came second in the Grand National on Suny Bay in 1998, describes how Bordes pursued him to a Newbury racing stable wearing a full-length mink.

Describing ‘Bazza’ as ‘a real party animal’ with an insatiable libido, Bradley also says he had a fling with model Angie Lyn, one of George Best’s exes. All knockabout stuff. But in 2001, when Wright was in his mid-40s, a darker side of his life emerged that explained how a jockey with only a handful of winners could live so high on the hog.

After a six-year undercover operation, HM Revenue & Customs had smashed what they described as ‘probably the most sophisticated and successful global cocaine-trafficking organisation ever to target the UK’.

Laden with cocaine supplied by Colombia’s Medellin Cartel, container ships would secretly moor off the Cornish coast and transfer their cargo to small yachts, which smuggled it into Britain through south coast ports. The kingpin behind this operation was Brian Wright (no relation to Barrie), nicknamed ‘The Milkman’ because, it was said, he always delivered.

When his gang was rounded up, the racing fraternity were shocked to hear fun-loving Barrie Wright was among those arrested.

Wright pictured with former Miss India Pamella Bordes at her birthday party in 1988

Although he was acquitted of conspiracy to import cocaine, in court he admitted having received generous rewards for supplying inside racing information to The Milkman, who laundered his £300 million cocaine fortune by betting extravagantly.

This disclosure displeased the drugs baron, who by then had fled to Cyprus but was arrested a few years later and jailed for 30 years.

A well-placed source told me that The Milkman — who was released in April 2020, just two months after Wright’s disappearance, having served half his sentence — still ‘hates’ Wright for his disloyalty.

Is this significant? The source suggests not — a view shared by Graham Bradley, who makes no secret of his friendship with The Milkman. From his retirement home in France, he confirmed the falling out but said he felt ‘100 per cent’ sure the cocaine baron had played no part in Barrie Wright’s disappearance.

Wright’s son Tommy concurs. And if The Milkman didn’t deliver vengeance on his father, he believes he knows who did.

Although Wright was absolved of cocaine trafficking, his involvement in the sensational case ended his playboy days. Ostracised by the racing establishment and banned from the sport for 15 years, he slipped back to Belgium, where he had taken refuge as the Customs dragnet closed in.

Did he settle in the affluent town of Brasschaat purely for its quaint cottages and tree-lined streets?

Or was there another reason why Wright rented an apartment there, 20 minutes away from Antwerp docks: the gateway to Europe’s £12 billion cocaine industry (110 tons were seized in Antwerp last year, plus large consignments of heroin and hashish) and close to the Netherlands, from where drugs are distributed across the Continent? Belgian police have long suspected the latter explanation. According to the city’s newspaper Gazet van Antwerpen, ‘over the past 20 years his name has regularly surfaced in judicial investigations into drug-trafficking and other forms of organised crime’.

The paper claims Wright was implicated in a major probe at the time he vanished.

With his old-school British manner and rakish good-looks, however, he cut a popular figure in Brasschaat, winning the affections of Winnie van Elst, a local beauty who was serving in a brasserie while finishing her studies.

‘He was 19 years older than me but he was handsome and extremely charming,’ she told me. A naive young woman from a conservative background, she says she at first knew nothing of his debauched, corrupt past.

Nor, she says, did she wonder why he went away for days, never taking her with him; or why he rented a second flat in Germany. He said he made his money by providing punters with racing tips via a mobile-phone subscription.

The first inkling that their lifestyle might have been funded less innocently came when their son, Tommy, was a few weeks old. Armed police stormed their flat and arrested Wright for his alleged role in The Milkman’s gang.

The alleged offence dated back to long before he met Winnie. And although the scales have since fallen from her eyes, back then she was convinced of his innocence.

Trying to avoid extradition, Wright even persuaded her to marry him while he was in jail on remand. ‘There were just ten people at the wedding and I wore black,’ she says. ‘My father was so angry, he wouldn’t attend. But I was so much in love that I would have done anything.’

The ruse failed and Wright was sent to Southampton for trial. Winnie and Tommy accompanied him; staying, she recalls, with Lady Chanelle McCoy, now the wife of top jockey Sir Tony McCoy, but then his girlfriend.

Winnie was ecstatic when Wright was acquitted. Yet within a year of their return to Belgium, she filed for divorce. Wright was ‘amazing with children and horses’ but he was so controlling and hyperactive that she found it impossible to live with him.

The clock winds forward almost 20 years, to February 2020. By now, Winnie is running a successful beauty salon in Brasschaat. Having moved elsewhere in Belgium and Holland, Wright is back in town, renting a swish, wraparound apartment on the top floor of a sought-after block in the main square. His son Tommy, then living mainly with his father, takes up the story.

Wright was a creature of habit, he tells me fondly. Each morning he rose early, read his English newspaper over coffee at a nearby cafe, then drove to an Antwerp gym. Then aged 64, he was impressively fit and youthful. With his nightclubbing days behind him, he usually returned to watch TV and retired to bed early, although he periodically returned to England — ostensibly to stay with friends in the horse-racing world and with family members.

Wright’s two daughters by a previous relationship are now in their 40s. He also has, or had, six siblings, including a younger brother who played football for Leeds United and Middlesbrough.

Old habits die hard, however, and he acquired another much-younger girlfriend, Gabi, a stunning Brazilian whom he met on his unexplained travels. Twice a year he would fly, club-class, to South America to see her, and sometimes she would stay with him. Wads of cash often lay around the apartment, but Tommy, then barely out of his teens, didn’t pry into his father’s financial affairs, presuming his income to derive from his interests in two racehorses and other related businesses.

The last time he saw his father they lunched, together with Tommy’s girlfriend, at his favourite Italian restaurant, Oregano, a short walk from his apartment.

Before they had finished eating, Wright left the table, saying he had to meet someone and would be back in a couple of hours.Such sudden diversions were not unusual. That evening, though, his father didn’t return home, and Tommy’s concern grew when, out of character, he failed to return calls to his mobile phone.

Then Tommy remembered a disturbing phone call he had heard, two days earlier. ‘Dad was angry, and he was saying, ‘Oh, this guy is coming over. I don’t know what he wants — he’s off his head. He wants to meet me.’ He didn’t seem scared, more angry — but when I asked him about it, he said I shouldn’t worry myself.’

As the hours ticked by, the implications of this call gnawed at him. Since his father could barely operate his computer, Tommy had all his passwords and examined his laptop for possible clues. They used the same travel website, Booking.com, so he also explored that.

Weirdly, it showed that Wright had made a reservation for that night, February 7, 2020, at a hotel just three miles from his apartment in Brasschaat.

Though booked under his name, it must have been for the man he spoke about on the phone. (By grim irony, the hotel chain shares its name — Van der Valk — with the recently-returned TV detective who plumbs the grisliest depths of the Low Lands underworld.)

Now ‘crazy’ with angst, Tommy dashed there. A receptionist confirmed that Wright had checked in and taken the key that afternoon (seeming ‘relaxed’ and ‘friendly’, she tells me), yet no one had entered the room. At this point, Tommy accepts, most people would have gone to the police.

Barrie Wright winning on Butler’s Pet. He rode five winners in the 1990/91 season comprising a pair of early season Devon & Exeter selling hurdles on Rosoglio for Trevor Hallett, and three on Chris Wildman’s handicap hurdler Doc’s Coat, the last of them at Newton Abbot’s Easter meeting on April 14, 1990

Events quickly took another twist, however. Among the dubious ‘friends’ who called Tommy to ask why Wright was unreachable, one said he had another method of contacting his father.

It was via EncroChat, his encrypted smartphone.

This system was abruptly closed, a few months later, after French and Dutch police hacked into it and made scores of arrests across Europe.

It was said that 90 per cent of the 60,000 subscribers were criminals.

The very fact that Wright felt it necessary to communicate in this shadowy manner surely tells us much about the true nature of his ‘business’.

When Wright’s friend messaged the device, he received replies by text message purporting to be from Wright himself.

From the wording and spelling, however, they were clearly coming from the kidnapper.

Tommy doesn’t know how much money he demanded, but refuses to believe his father owed him anything, saying loyally that he never fell into debt.

The negotiations dragged on for several days, with details constantly being relayed to Tommy.

He was then just 20 years old and, fearing that involving the police might further jeopardise his father, he was acting alone. The anxiety he must have felt is difficult to countenance.

It was only after eight days, when the messages stopped — ‘something had obviously gone very wrong’, he surmises — that he reported the disappearance.

Perhaps understandably, given his tardiness, he says Antwerp detectives interrogated him harshly and confiscated his phone and computer, seemingly regarding him with suspicion. Wright was classed as a ‘worryingly missing’ person, and an appeal for information was issued.

The public prosecutor’s spokesman told me it was not ‘100 per cent certain’ that Wright was murdered.

Yet Tommy is under no illusions as to his fate.

He accuses the police of downgrading the urgency of the case because they had scant regard for his father — a claim supported, he says, by the fact that it took them a full year to find his car, a rented white VW Golf, even though it was left close to the hotel.

It spurred him to make his own enquiries. Mindful of his safety and that of his family, he declines to say more.

Intriguingly, however, another source tells me the suspected kidnapper — a notoriously violent Mancunian — was once Wright’s friend. He even stayed with him in Belgium and joined him on a family holiday.

The insider says the police have been given his name, and that Tommy tenaciously traced the man’s family, urging them to help with the investigation. To no avail. How, then, was Barrie Wright — a wiry man who would have put up a fierce struggle, those who know him say — spirited away, that February afternoon?

Soon after her ex-husband disappeared, Winnie was told that a man had been seen grappling with three others, on the road near the hotel, before being bundled into a black van. This was around the time Wright checked in.

For many months afterwards, Tommy suffered terrible thoughts about his father’s fate. Bodies quite often wash up in Antwerp docks, and he feared the phone would ring whenever one was reported in the news.

Then, soon after Wright disappeared, police discovered a gangland torture chamber, a few miles across the Dutch border. The instruments it contained included pliers, scalpels, blow torches. There were dentists’ chairs with straps to hold the victims.

Having learned, from a Vodafone bill, that Wright’s handset was last switched on in Holland, three days after he was taken, Tommy imagined his father might have breathed his last in this appalling place. Thankfully, police later said the chamber had not been used.

Now rebuilding his life as an events manager in Antwerp, this engaging young man has set aside these dark thoughts, but he has little doubt that his father was murdered.

Whatever wrongs he committed, Tommy says his father deserves justice. ‘Dad was one of a kind — an inspirational father loved by everyone who knew him,’ he says.

Perhaps so. Yet somewhere along the track, the playboy jockey made a vengeful enemy whom he couldn’t escape, no matter how far he rode.

Source: Read Full Article