Cancer made me realise how truly magical ordinary life is: SYLVIA PATTERSON reveals her joy at returning to the ‘miracle of normality’ after two gruelling years of treatment

- UK writer Sylvia Patterson writes about returning to life after cancer treatment

- READ MORE: What’s behind the worrying rise of cancer in young people?

I’m staring at my evening meal. It’s a small mound of cold egg mayonnaise — one mashed boiled egg, liberal mayo, no salt — marooned on a dinner plate like a morsel fallen off a badly constructed vol-au-vent.

This week, the mouth ulcers are so bad — as if my mouth is a hive of dive-bombing wasps — that this is all my ravaged mucus membrane can tolerate.

I’m unable to brush my teeth, so a mouth rinse must do. Also banished to history are hot drinks, alcohol, all forms of satisfying crunch, even a refreshing shower; enormous surgical dressings mean I’m dumped in six inches of puddle bath instead.

Then, because of heavy morphine, there’s the constipation. Oh, the constipation. Throughout life, ladies, forget needing the earth to move — what we really need is our bowels to do the same.

It’s late spring 2020. It has been four months since I was diagnosed with breast cancer and today we’re all in lockdown. For me, though, because of chemotherapy, even a walk in the park spells peril.

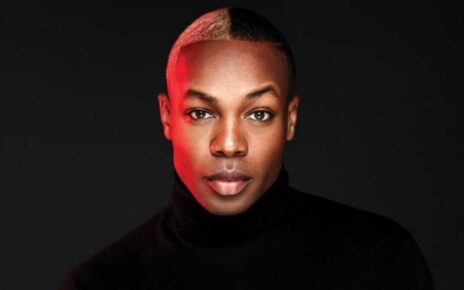

Sylvia Patterson, pictured, charts, in a powerful new book – her two years of gruelling treatment

I’m 55 and officially a ‘vulnerable’ person who must shield my barely functioning immune system; if a Covid-carrying jogger heavy-breathes down my neck I’ll be even more likely to die from that disease than the cancer already trying to kill me.

I am, therefore, incarcerated, and have become the most boring person on Earth. For four months this illness and its treatment are all I talk about, think about, am asked about and know about.

As the days trudge by, I know exactly what I want from life, more certainly that I’ve ever known: life as it was before, when it was ordinary, humdrum, average.

What I want from life is . . . clean teeth. A hot cup of tea. The snap of a crisp. A piping shower. That glorious walk in the park. A successful trip to the bathroom. When I was living what I’ve come to call the miracle of normality.

As soon as you’re sick on any level — be it a heavy cold, a broken bone, anywhere on the spectrum of disease, both physical and mental — all you want is your old life back. The one you didn’t fully realise was everything you’ll ever need, brimful of everyday banality. Cancer is this, literally on steroids.

Like all newly diagnosed cancer patients, during the three-week wait for biopsy results — which started Christmas week 2019 (Merry Christmas!) — I absolutely believed I would die, probably within a year.

Instead, I was spectacularly fortunate. I not only had one form of breast cancer but two, a tumour undetected at the base of my right breast, and one named Paget’s disease in the right nipple, the visible sign (raw, scabby, weepy) which took me to the GP, an early diagnosis and through The Process that saved my life.

For 20 months — from January 2020 to autumn 2021 — the treatments were brutal: three types of chemotherapy (the first resulting in two five-night emergency stays in hospital with potentially fatal sepsis), three weeks of radiotherapy, a mastectomy, a reconstruction.

Bowelbabe: Dame Deborah James, pictured, died last year. She was praised for her campaigning work

Then, two months of failing reconstruction, where my breast implant inflated as if affixed to a bicycle pump, turning scarlet and boiling to the touch. Like a miniature Hindenburg balloon on fire, threatening to hoist me into outer space.

Eventually, it was amputated, leaving me with half a mutilated chest wall and, with the rapid weight loss, one lonely, bounce-free breast with the constitution of a folded oven glove.

I’d dealt easily with no eyebrows, no eyelashes and threadbare hair; those things were temporary. One breast permanently, though, was a shocker, bringing a profound sense of loss, shame and self-consciousness that has taken two years to overcome fully. But I have overcome it. This summer, at home, I’ve often worn shorts, no top, and a new lacy black mastectomy bra (implant replaced by the NHS-provided prosthesis or ‘breast form’).

A day’s merry wandering in shorts and bra is something I’ve never felt bold enough to do before — ever — prompting my heroically stoic partner of 20 years, Simon, to announce approvingly: ‘You look like one of MC Hammer’s backing dancers’. Who knew this could be a consequence of cancer?

There is no such thing as the fabled cancer ‘battle’, with its implication that only the ‘strong’ survive. What you endure instead is The Process — the grind through a back-to-back series of treatments, an exercise in both patience and cultivating a positive mental attitude.

There were days when I felt crushed, defeated and outright depressed, especially the days post-mastectomy, when I was still attached to surgical drainage tubes. The pain was so acute I couldn’t manoeuvre out of bed without Simon’s aid, gripping on to his arm, inching forward, wincing, with the one-eyed look (he quipped, hoping to make me laugh) of ‘Thom Yorke from Radiohead’.

To add style-free insult to injury, I couldn’t even wear feel-good clothes: chemo chilled me to the bone so that my body was constantly trembling and my lifelong staple, the sparkly disco top, was replaced by thermal vests and an enormous, shapeless, thick-knit jumper more befitting a storm-lashed Hebridean trawlerman.

Catching myself in a full-length mirror one day, I gasped out loud, seeing an alarming amalgamation of a shrunken old lady and a decomposing Yeti.

No wonder, then, when the bones begin to thaw, when the wounds finally heal, when the flickering light of your previous life comes dancing through the darkness, your perspective shifts for ever. Of all the things a life-threatening disease taught me, not least how much I did not want to die (and why the NHS is the very best of us), the biggest lesson turned out to be the simplest: without the basics, we have nothing. So, cherish them.

In summer 2021 Simon and I celebrated the end of the final, year-long chemo with a two-day trip to Cambridge. As a lifelong music journalist, who saw Covid finish off the last music magazine I worked for (Q, which folded in summer 2020), times were financially tight.

Sitting by the edge of the River Cam on a stunning mid-July day, we dangled our bare feet in the cooling waters, watching geese float by, and I felt suddenly overcome, arms stretched outwards, by a feeling of both intense freedom and surging, profound happiness. I’d never felt so fortunate in my life.

I have never been so fortunate in my life.

Because I didn’t die. Where so many I’ve known and loved did. I was mutilated, physically feeble and barely employed but I had everything I could ever need: my life partner, our home, my friends and family across the country, a blue sky overhead, a sparkling river in a stunning historic city, a hearty picnic (with crisps), two bottles of rosé wine in a plastic bag full of ice cubes and a body that wasn’t trying to kill me any more.

Today, fully nourished and healthy again, I feel as well as I’ve ever felt. As soon as I could walk in the park, I walked every day — and still do, up to three miles daily. It’s the greatest tonic for mental health. Food has never tasted so delicious. Or an ice-cold pint of summertime cider.

When I wear one of my sparkly disco tops, I think about the importance of feel-good clothes, until they’re not important: they are embellishments of course, the fancy sprinkles on the cake, where it’s the quality of the plain old bath sponge that counts.

This summer I was reminded of former Wimbledon heroes Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova, those deadly rivals turned closest friends, whose astonishingly parallel lives included cancer in 2022.

Interviewed together in the Washington Post, their reaction to this disease, too, was to reinforce their previous lives. After Chris’s diagnosis (ovarian cancer, followed by a preventative double mastectomy), came her renewed enthusiasm for punishing training schedules, beseeching her doctor ‘Can I get on a treadmill?’

After Martina’s diagnosis (throat and breast cancer) and thinking ‘I could be dead within a year’, she turned to her youthful passion for swanky cars, wondering what she should drive in her final year, a Bentley or a Ferrari?

She, too, had become alarmingly underweight and frozen cold, wearing ski vests to appointments. The record-breaking nine times Wimbledon champion needed two hands to drink a glass of water. ‘Everything,’ she noted, ‘felt just wrong.’

Today, the pair are survivors, cancer-free and, for Chris, life feels so much simpler, clearer and, in her words, ‘uncluttered’.

Also this summer came bolstering words from another of my sporting heroes, snooker MC, sports commentator and irrepressible life enthusiast Rob Walker. In June he completed his Absent Friends Tour, a 1,000-mile running/cycling charity fundraising odyssey from John O’Groats to Land’s End.

This was his reaction to two years of sledgehammer grief; he lost three of his close friends, all in their late 40s or early 50s, while his son lost his best friend, aged nine, suddenly in his sleep (Rob spoke at all their funerals).

The experience had left him, he wrote online, ‘with a heightened appreciation of life, love and the determination to focus on the beauty of the simplest pleasures. Like a run down a country lane with nothing but the sound of birds and bees on your ear’. He quoted the immortal line at the close of prison survival epic The Shawshank Redemption: ‘Get busy living. Or get busy dying. That’s goddamn right.’

Get busy livin’. It’s a line I also quote at the end of my new book, Same Old Girl, my survival story through the prison of cancer, and it’s a worldview I attempt to live by every day, or at least remind myself to remember.

Such sentiments, as hard won as they are, can almost seem too simple to say. The trick is to believe it, deep down, in the cells that form us, the same cells that can mutate and try to kill us, often exacerbated by stress and negative thinking.

These bolstering messages are all around us if we choose to hear them. All those can-do, seize-the-day, breast cancer survival stories from, in recent years, Newsnight’s Victoria Derbyshire, Sky Sports presenter Jacquie Beltrao, Countryfile’s Julia Bradbury, TV property expert Sarah Beeny and the Royal Family’s Sarah Ferguson, who could also tell us a thing or two about the pointlessness of wealth if you do not have your health.

Heed the lessons, too, of those who didn’t survive, such as Dame Deborah James, Bowelbabe, with her immortal parting words: ‘Find a life worth enjoying, take risks, love deeply, have no regrets, and always, always have rebellious hope.’

What she would have given to have simply stayed alive, as a non-famous, non-campaigning, non-dame, ordinary woman raising her precious family instead, living her own version of the miracle of normality. For those of you living that miracle today don’t wait to get busy livin’ until you, too, are diagnosed with a life-threatening disease (which is, sadly, not unlikely).

Don’t wait until either you, or your family, or your friends, begin to die (which is inevitable). Live now. Right now. You just can’t count on tomorrow. Make sure you can count on today.

SAME Old Girl: Staying Alive. Staying Sane. Staying Myself (£20, Fleet) by Sylvia Patterson is out now.

Source: Read Full Article