JESSICA HONNOR: How West End shows turned into the Wild West… Deafening singalongs, drunken hecklers and police called to break up fights as rowdy punters halt a performance of The Bodyguard

A typical Friday night in the West End warzone: an actor, in the middle of an emotional scene from hit musical Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, has stormed off stage for a second time as a fight breaks out halfway down a row of seats in the auditorium.

Ushers scurry in to eject the combatants. Members of the audience crane their necks to see the action.

This is not the show we paid for — but it’s the kind of drama that has become wearily familiar to me.

I’ve sat through the annoying: like the man who, last week, kicked my chair in time with my favourite songs at the new musical Operation Mincemeat. And the downright dangerous: ushers suffering physical abuse as they tried to calm crowds.

Just a week or so ago, police were called to a ‘mini riot’ at the Palace Theatre in Manchester, where The Bodyguard — a so-called ‘jukebox musical’ featuring the songs of Whitney Houston — was playing.

Just a week or so ago, police were called to a ‘mini riot’ at the Palace Theatre in Manchester, where The Bodyguard — a so-called ‘jukebox musical’ featuring the songs of Whitney Houston — was playing

There was trouble from the off, when a handful of people who wouldn’t keep quiet had to be ejected during the first scene

There was trouble from the off, when a handful of people who wouldn’t keep quiet had to be ejected during the first scene.

A fight broke out later, because some of the audience were screaming the lyrics of I Will Always Love You, the show’s big number, so loudly that lead actress Melody Thornton, a former member of The Pussycat Dolls, could not be heard.

Videos of two women being ejected by security went viral and Thornton put out a message on Instagram the following day, apologising for having to abandon the performance and saying that she had ‘fought very hard’ to continue singing, but that it had been impossible. It was unsafe.

All of which begs the question: do the producers of these popular musicals have only themselves to blame?

Earlier this year, The Stage reported that the Ambassador Theatre Group was working with producers to tone down advertising campaigns that could encourage rowdy behaviour, such as posters boasting that a show is ‘the best party in town’ or gets the audience ‘dancing in the aisles’.

As a theatre critic — occasionally reviewing for the Daily Mail — I probably don’t see the worst of it, as I usually attend Press nights when the audience includes various critics and often the cast’s family and friends.

But I go to the theatre frequently enough to know that crowd behaviour is often shockingly bad.

A typical Friday night in the West End warzone: an actor, in the middle of an emotional scene from hit musical Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, has stormed off stage for a second time as a fight breaks out halfway down a row of seats in the auditorium

When I took my mother to see Jersey Boys for her birthday last year, Frankie Valli’s falsetto was drowned out by the audience’s tuneless howling. One star recently tweeted: ‘It’s hard enough trying to pitch the final word of My Eyes Adored You without 30 people trying to get in before me.’

And at an Oxford performance of Beautiful: The Carole King Musical, we moved seats to escape a man who was not only chattering throughout but also, inexplicably, playing air piano. I’m told that more and more ushers are wearing body cameras and having to learn de-escalation techniques, such as keeping their tone and body language neutral, as they deal with increasingly combative audiences and vile abuse.

A new survey from the Broadcasting Entertainment Communications and Theatre Union (Bectu) reveals that almost 90 per cent of theatre staff have witnessed bad behaviour, with more than 70 per cent saying it had worsened since the pandemic lockdowns. Almost a third said their venue had been forced to call the police at least once.

I felt something had changed post-Covid when, at one of the first shows I saw after theatres were allowed to reopen, a theatregoer cornered an usher to yell about a minor point of dissatisfaction.

It struck me that people had lost their respect for normal social rules when it came to interacting with others after months of being stuck at home.

Many appear to have adopted a ‘living-room mentality’ — forgetting they are surrounded by fellow human beings rather than relaxing on their own sofas.

I’ve watched, horrified, as people have taken off their shoes and socks and rested their feet on the back of the seat in front of them — or, God forbid, the stage.

Some noisily devour three-course picnics, put drinks and coats on the ledge of the orchestra pit above appalled musicians, or scroll through social media on their mobile phones.

Is there anything more annoying than the glow of someone’s phone in front of you during a performance? The constant stimulation provided by social media is giving people such short attention spans they can’t even get to the interval without checking their feeds.

A performance of The Bodyguard was stopped early after audience members sparked chaos

Alison Hammond apologises after being slammed for ‘encouraging’ disrespectful audiences following ‘mini riot’ at a theatre in Manchester

Sorry: Alison Hammond has apologised after being slammed for ‘encouraging’ disrespectful theatre audiences on This Morning

But drink is the real culprit: during the West End musical Bonnie And Clyde, a gaggle of drunks noisily arrived late, mid-song. No sooner had they sat down than they were knocking drinks over, arguing with their neighbours and picking a fight with the beleaguered usher who tried to eject them. At a performance of Cabaret, a drunken chap pushed against a fellow audience member who went flying down the aisle.

Of course, it’s in the theatres’ interests to make money from selling drinks at their bars (especially since the lean pandemic years), but when do we say enough is enough?

People who are clearly drunk should be turned away at the door. In fact, introducing breathalysers wouldn’t be a step too far.

The best-behaved performance I’ve seen recently was a matinee of The Woman In Black, filled with school children — where, of course, no one was drinking (though I’m sure the teacher next to me was in need of a G&T by the end). It’s crazy that children are behaving better than adults.

I also believe the escalating price of tickets is a factor. Some seats for shows featuring big names such as Normal People star Paul Mescal, who is currently treading the boards in A Streetcar Named Desire, cost £300. After forking out such huge sums, a significant minority appears to think it gives them carte blanche to behave how they like.

And this sense of entitlement often stretches beyond the auditorium — Mescal has spoken about being groped at the stage door; and performers including Carrie Hope Fletcher, star of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Bad Cinderella, tell of the abuse they receive if they don’t stop to sign autographs or pose for selfies.

I have seen fewer problems at venues such as the National Theatre on London’s South Bank. Some will suggest this is because subsidies allow them to put on more high-brow fare that attracts a different type of audience, but bad behaviour isn’t limited to musicals.

One man listened to a cricket match on the radio throughout one cultural gem I saw, while a chap with an orchestral ringtone received multiple phone calls during another, with the lead actress pausing to ask him: ‘Is everything OK? Can we continue?’

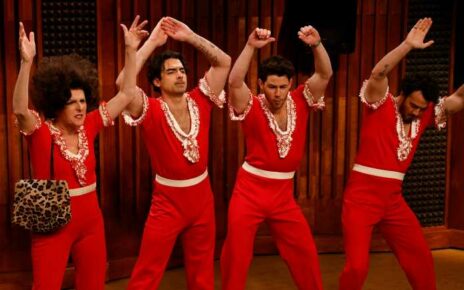

Performance: The show was paused in its first act as staff were forced to drag out several people and then was halted again just 10 minutes from the final curtain (Melody on stage The National Lottery’s Big Night Of Musicals)

Some argue that snobbery has taken over theatre and if the industry wants to attract new audiences — especially those from working-class backgrounds — it has to loosen up.

Actor Mark Rylance has gone so far as to blame the performers themselves for disruptions, saying: ‘If they’re [audiences] making noise then you’re not . . . telling the story well enough.’

I don’t recall any trouble during his rapturous turn in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem last year, so perhaps he has a point. However, I don’t think it’s elitist to want to spend two hours enthralled by a show, uninterrupted by phones pinging or raucous singing.

Yes, much of the joy of theatre — right back to the rowdy pit at the Globe in the 1600s — is that it is a shared experience, but surely that shouldn’t include drunkenly belting out Whitney Houston songs so loudly you have to be dragged away by the police.

Source: Read Full Article