Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

In over 40 years, not a single young person had died in detention in Western Australia. That changed last week. Will it surprise you to know the boy was Indigenous?

The 16-year-old boy, who had not been convicted, was found unresponsive in his cell. He had tried to kill himself. A week later, he died. WA’s Corruption and Crime Commission is now investigating, having received an “allegation of serious misconduct”.

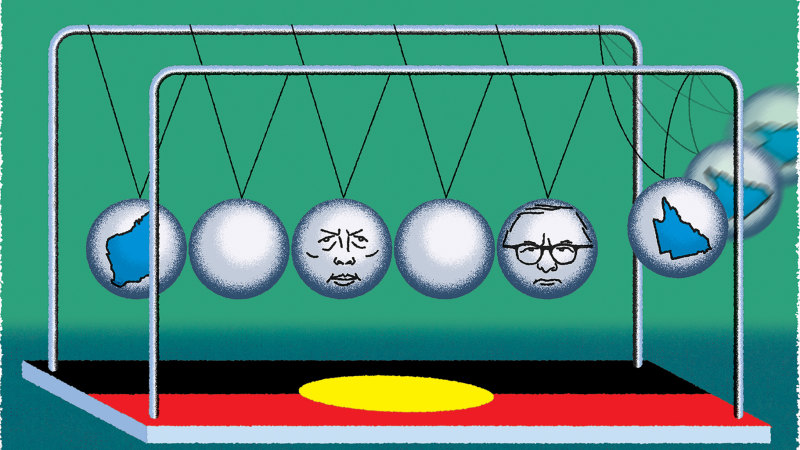

In the wake of the referendum, specific questions that need answering. But there are broader ones too.Credit: Jim Pavlidis

There are specific questions that need answering. But there are broader ones too: about the attitude that allows Indigenous people to keep dying in custody. After the suicide attempt, but before the boy had died, the premier of that state said the place where he was kept, Unit 18, didn’t meet care and safety standards, but was “a necessary evil” while new detention arrangements were being made – a statement of remarkable thoughtlessness or cruelty.

Unit 18 is a youth detention area inside an adult maximum security prison. And WA is not the only state now facing questions over its treatment of children. In August, the Queensland government took action to make sure it could continue keeping children in “watch houses” – where they have been kept in awful conditions, including alongside adult detainees. To do so, it had to suspend its human rights laws. We know that Indigenous youth, like Indigenous adults, are over-represented in our prisons.

It should be extraordinary that all of this happened in the lead-up to a referendum aimed at delivering on the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which specifically addresses the issue. Two sentences make a sharp point: “Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people”.

More than 30 years ago, the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was held; we have still failed to respond in any comprehensive way to its findings. As a country, we seem not much to care. As the Uluru Statement makes clear, there are really only two choices. Either we believe our First Peoples are innately criminal and that nothing is to be done, or we understand they are not, that we must act, and can’t be bothered. Both are awful.

And so, yes, it should be extraordinary that when we were supposed to be confronting the disadvantage in our midst we were instead perpetuating it. But actually, it makes perfect sense because in the end, now that we know the result of the referendum, we can see these events are demonstrations of the same consistent attitude: a failure to listen.

Noongar author Claire G. Coleman wrote of crying herself to sleep after the result. Plainly, lucidly, she wrote that she could see only one sensible interpretation: “The people of Australia simply don’t want Indigenous people to have a voice in our own affairs. They don’t want us advising on laws and policies that affect only us. If Australia wanted to listen to Indigenous people, it would have voted Yes.”

Another thing that should be extraordinary (but isn’t) is the indecent haste with which so many of this nation’s senior journalists declared the referendum had little or nothing to do with racism. Those who did acknowledge it largely did so sparingly, perhaps in passing. And so it has been fascinating, as the week of silence ended, to hear more from Indigenous people supporting Yes. Those statements canvass many subjects, but racism is an important one. Three land councils released a statement saying the vote “cannot be separated from a deep-seated racism… It is fair to say that not everyone who voted No is racist but also fair to say that all racists voted No.”

Perhaps ironically, in the aftermath of the result, the decision to go ahead with the vote might assume even greater significance as an act of a prime minister listening to Indigenous Australians.Credit: Bill Blair

Writer Daniel James concluded, “First Nations people have been judged by the colour of their skin” – Australia had “failed its own character test”. Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation, an ally group, reported, “We are hearing that for many, the unfolding events of 14 October felt like an unparalleled act of racism by white Australia.” Of the campaign itself, Thomas Mayo wrote, “The racist vitriol we felt was at a level not seen for decades in Australia.”

Of course, it is acceptable to analyse the results and reach different conclusions. And much of the punditry I refer to preceded these comments. Still, we should ask how likely we are now to properly consider Indigenous responses; how willing we are to let them reshape our understanding of what has taken place. If we simply dismiss them without properly grappling with them, then it is hard to escape the bitter consistency: having voted not to listen, we are now determined not to listen even to what Indigenous people say about that vote.

Some final notes on the politics to come. A depressing aspect of past days has been the rush in some quarters to build on No: Tony Abbott’s assertion, say, that we must respect the vote by abandoning or scaling back acknowledgements of country and the flying of the Indigenous flag. The exploitation of racism in different forms will come now too: as Niki Savva wrote last week, around immigration. An interesting aspect of the Yes campaign was how many senior Liberals were involved. What is their stance now? How much will they do to prevent such trends? Racism breeds racism; you can’t allow the encouragement of resentments against one group and expect others to escape unscathed.

Then there is the prime minister. Amid all the suggestions that nothing has been achieved, that things are even worse, it is interesting to watch Yes supporters, who have every right to criticise Anthony Albanese for the loss, praise him instead. I suspect non-Indigenous people struggle to grasp the importance of a government having listened. Perhaps ironically, in the aftermath of the result the decision to go ahead with the vote might assume even greater significance as an act of listening.

Ultimately, though, a prime minister must act. So much of consequence is in the hands of premiers – who are, at present, overwhelmingly Labor. The premiers of WA and Queensland, where Indigenous children are at risk in detention, are both Labor. If Albanese remains determined to make an awful situation better, he will have to confront his powerful colleagues, one way or another. It is an unavoidable test.

Sean Kelly is author of The Game: A Portrait of Scott Morrison, a regular columnist and a former adviser to Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article