By Matthew Knott

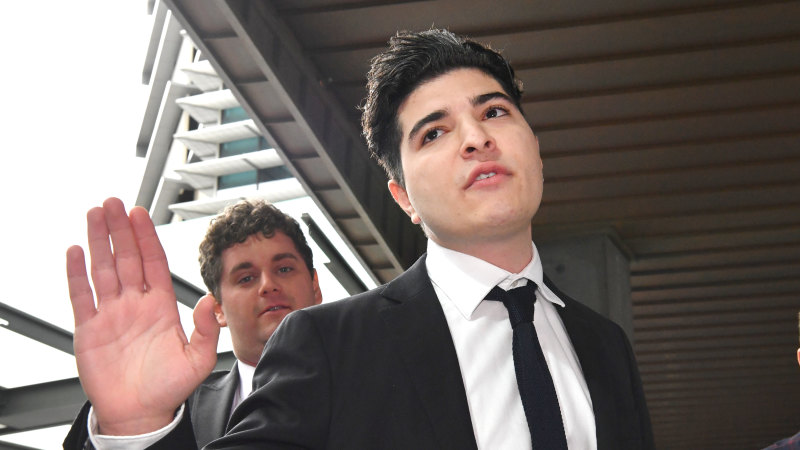

Drew Pavlou: “They think I’m a racist who likes to stir people up. I cop so much bullshit, unfortunately.” Credit: AAP

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

As he gazes at the sails of the Sydney Opera House – gleaming white from afar, the colour of coffee-stained teeth up close – Drew Pavlou feels at once enchanted and deflated. Enchanted because it’s a blissful sunny day in Sydney, and this is his first time standing on the steps of Australia’s most celebrated building. Deflated because his plan to use the day to publicly shame the Communist Party of China (CCP) against the backdrop of various Sydney landmarks is turning out to be an epic fizzer.

That’s the trouble with real life. Reality gets in the way. The 24-year-old Brisbane-based activist, a child of social media, does most of his activism virtually and has made a name for himself that way. Before today, I’d only encountered Pavlou online, through his prolific posts on Twitter, where he has 65,600 followers, and the wash of headlines that invariably follow in his wake.

Pavlou is an unlikely figure: a young, once exemplary student of Greek heritage, now devoted to criticising the Chinese government and its human rights abuses. He’s emblematic of the new breed of lone protester, with a strong online presence and scattergun style of activism. He doesn’t belong to any organised group. He still lives at home and works mostly out of his book-filled bedroom.

Drew Pavlou, right, with fellow activist Max Mok, staging a book-burning of Xi Jinping’s works at the Chinese consulate in Sydney.Credit: @drewpavlou/Instagram

Pavlou and I meet at Sydney airport, where he has arrived on a flight from Brisbane. He is booked to fly to India later that afternoon to meet the Dalai Lama, an invitation organised through the pro-Tibet movement. The plan is for me to shadow him while he makes the most of his stopover day in Sydney, which will be less about sightseeing and more about launching the kind of spontaneous and haphazard protest actions that have helped make his name. While others meticulously plan their protests, Pavlou treats activism more like improvisational jazz, making things up as he goes along. We hop in a taxi and head to Circular Quay, where he’s meeting up with a group of friends.

Juggling three bags and with his clothes crumpled from travel, Pavlou cuts a dishevelled figure. His jet-black hair is clipped short at the sides and left long on top, a style not unlike that of the North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un. Already, there are specks of grey. Activism seems to be taking its toll.

In person, Pavlou is more vulnerable than his strident and often self-aggrandising posts would suggest. He tells me he feels misunderstood, with some of his actions interpreted as tarring Chinese people in general, not the regime in particular. “People get the wrong idea about me,” he says. “They think I’m a racist who likes to stir people up. I cop so much bullshit, unfortunately.” It’s true that wherever Pavlou wanders, trouble seems to follow. In the previous 18 months, he has been arrested on suspicion of threatening to blow up the Chinese embassy in London; charged with offensive behaviour by NSW Police for holding up a sign saying “Xi Jinping, f— your mother” in a suburb with one of the country’s largest Chinese-Australian populations; and was unceremoniously bundled out of a Parliament House cafe in Canberra by the Australian Federal Police.

Pavlou’s provocative antics and feisty social media posts are polarising. “Essentially, he is an attention hog who terrorises people into silence. He’s more of a ranter than an activist,” says Erin Wen Ai Chew, founder of the Asian Australian Alliance, an advocacy group for Australians of Asian heritage. Kyinzom Dhongdue, a veteran Tibetan activist who has become a close friend of Pavlou, counters: “Drew has been speaking up for my community and other communities that have been colonised by the Chinese government at great personal cost. He’s sacrificed so much.”

Vicky Xu, a senior fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute who wrote an influential report on the alleged forced labour of the Uyghur minority in China, says: “I’ve heard from university tutors that Drew Pavlou is a role model and a hero for a lot of 18- and 19-year old boys. I think his mere existence is seen as dangerous and unwelcome by the Chinese government.”

“I think his mere existence is seen as dangerous and unwelcome by the Chinese government.”

At Circular Quay, we meet up with Pavlou’s friends. All are exiled pro-democracy activists from Hong Kong, ready for an afternoon of activism. The original plan had been to unfurl a huge anti-CCP banner emblazoned with slogans in Mandarin such as “We want reform, not a Cultural Revolution” across the Harbour Bridge. The stumbling block is that the banner hasn’t arrived from London in time. It’s probably for the best. It turns out Pavlou and his friends hadn’t thought through how to display the flag from the bridge, or investigated whether doing so was legal. “It’s a serious offence, I think,” Pavlou says nonchalantly. “No one thought about it, really.”

With Sydney Harbour sparkling before them, he and his comrades brainstorm other ideas. “Why don’t we print out a Xi Jinping effigy and burn it?” someone suggests. No, that would take too much time. Instead, they decide to buy a book by China’s president-for-life and set it on fire in front of the Chinese consulate, a short drive away in the inner-west. Suddenly Pavlou is buzzing with energy, like he’s chugged a can of Red Bull. After buying the necessary cigarette lighter and finding, in a bookstore in Chinatown, a pristine $5 copy of Xi Jinping: The Governance of China, a collection of the President’s speeches and writings, Pavlou orders another Uber to take us to the consulate. By now it’s just three of us: Pavlou, me and his friend Max Mok, a Hong Kong-born pro-democracy activist.

The Chinese consulate in Camperdown is an imposing compound surrounded by high walls and barbed wire fencing. It looks more like a prison than a diplomatic station. Pavlou and Mok set Xi’s book on fire and giggle like mischievous schoolboys. The consulate lies in a quiet backstreet with little passing traffic. Only its security guards witness the stunt as it happens. Never mind. Pavlou knows the footage will play well online. As a security guard grudgingly cleans up the pile of ash from the burned book, Pavlou offers to do the dirty work himself. “Let the record show I’m a polite protester!” he says.

After the book-burning, Pavlou and Mok head to a pub to unwind. Pavlou orders a lemon, lime and bitters. “Drew doesn’t drink or do drugs or party,” Mok says.

Pavlou nods. “People have asked me if I’m on cocaine because it’s like I’m on a natural high from life.” He describes himself as “hyperactive” and was recently diagnosed with ADHD.

The mood of bonhomie at the pub is shattered when Pavlou looks at his phone. It seems Brisbane City Council and the Queensland government have just received online bomb threats, sent out in his name. “IF YOU DON’T END BRISBANE’S TIES WITH THE CCP, THEN I’M GOING TO BLOW UP YOUR COUNCIL BUILDING AND I WILL SHOOT EVERY LAST ONE OF YOU!!” reads the email to the council. The email to the Queensland government threatens to plant a bomb in the state parliament.

Pavlou says the emails are the latest in dozens of fake threats sent under his name, with his email address, as part of an alleged campaign by the CCP or its supporters to smear him. He calls the police to report the fake threats, fearful the matter could somehow get in the way of his trip to meet the Dalai Lama. “This is f—ing cooked!” he says. “They’re trying to f— with me.”

Pavlou (left) and Mok flagging the story of Peng Shuai, the Chinese tennis star who has largely disappeared from view after accusing a former high-ranking member of the Chinese Communist Party of sexual assault. They planned to distribute the T-shirts at the 2022 Australian Open.Credit: AP

He’s stressed, but also vindicated. As he sees it, he’s locked in a battle with a repressive superpower and he’s being noticed. “The level of harassment I get is an index of my effectiveness.”

A few weeks after his trip to India the Pavlous host me for dinner at their home, a modern townhouse in a well-to-do riverside suburb in Brisbane. They’re a boisterous, welcoming crew. His mother, Vanessa, a retail worker, has served a traditional Greek home-cooked meal and Pavlou’s girlfriend, who Pavlou has been dating for a year and is clearly smitten with, has joined us. She does not want to be identified because she fears being publicly associated with Pavlou could damage her career. (“I hope we’ll be a power couple one day,” Pavlou says.)

Pavlou’s parents have never been politically active. Both are lifelong Liberal Party voters and are far more conservative than their son, who is also a devotee of US democratic socialist Bernie Sanders. “My dad tells me to get rid of this obsession,” Pavlou says. “He’d like me to get a real job.” Pavlou became interested in China in 2019 when he was studying philosophy and politics at the University of Queensland. At the time, Beijing was cracking down on pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong and it was becoming widely known the regime was locking up Uyghurs in concentration camps in the Muslim-majority province of Xinjiang. That year also marked the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, which falls on Pavlou’s birthday. He began questioning why left-wing activists on campus were so passionate about the Israel-Palestine conflict, Indigenous disadvantage and refugee rights but, in his view, had little to say about China’s egregious human rights violations. “The hypocrisy really stuck with me. I thought I’d just do one protest,” he recalls.

At this stage Pavlou had a near-perfect grade average, had received several awards for academic merit and won the university’s undergraduate poetry prize. He’d never had any disciplinary difficulties or been involved in protests. That all changed on July 24, 2019.

Pavlou was deluged with death threats. “I will hire a killer to kill your family,” said one.

Pavlou’s first protest was so disorganised that he slept in and arrived half an hour late for his own event. Only a handful of others had signed up to participate. At best, he thought, the protest might be covered in the university newspaper and attract a few hundred likes on Facebook. But as he and his fellow protesters chanted “Xi Jinping has got to go” and called on the university to end its ties to China, the crowd swelled to 500. Many were Chinese nationalists who appeared significantly older than university students; some wore earpieces. Suddenly, one of the Chinese nationalists launched himself at Pavlou and grabbed his loudspeaker. A brawl broke out as the counter-protesters tore up signs defending Hong Kong and blasted the Chinese national anthem. The following day, Pavlou’s Facebook page was deluged with death threats. “I will hire a killer through [the] deep web and then kill your family,” said one. “Your mother will be raped till dead.”

His terrified parents, fearful that their other children’s safety could be at risk, pleaded with Pavlou to stop. The protests attracted international media coverage.

Radicalised by his first protest action, Pavlou was inspired to continue. As the coronavirus swept the globe in March 2020, Pavlou donned a hazmat suit and stood outside the university’s Confucius Institute, one of an estimated 550 centres around the world dedicated to promoting Chinese language and culture. Critics say the institutes form part of the CCP’s global propaganda network. Pavlou posted on Twitter that he was locking down the institute “UNTIL BIOHAZARD RISK CONTAINED”.

Pavlou in Ukraine, April 2022.

That protest is still used against him as proof his activism extends beyond criticism of the Beijing regime to generalised anti-Asian hate. Gerald Roche, a LaTrobe University linguist, accused Pavlou in a blog post at the time of bolstering “narratives that racialise and ethnicise COVID-19, portraying Asians as sources of disease”. He filed a complaint against him with the university. A month later, Pavlou received a 186-page document from the university’s disciplinary board. It accused him of 11 counts of misconduct and warned he could be expelled. Some of the allegations were trivial, others more serious, including those based on social media posts in which he referred to students from the university’s finance and economics department as “c—s” and called a PhD candidate a “disgusting mindless slob”. Pavlou acknowledged some of his language was poor, and put it down to being upset about a friend who had taken their life.

The disciplinary board initially found him guilty of eight of the allegations and suspended him for two years. The punishment shocked university Chancellor Peter Varghese, who said there were “aspects of the findings and the severity of the penalty which personally concern me”. On appeal, Pavlou was found guilty of only two of the allegations and the suspension was reduced to one semester and 25 hours of community service on campus. While the University of Queensland insisted the punishment had nothing to do with Pavlou’s political views, the ordeal triggered a landmark parliamentary inquiry into the national security risks affecting the Australian higher education and research sector.

Once he discovered politics, Pavlou couldn’t get enough. By the age of 23, he had already been a member of three political parties: Labor, the Greens and the Bob Katter Party. Although Pavlou is far to Katter’s left on social issues, they share an aversion to Australia’s reliance on trade with China to power its economic growth. When Pavlou lost the pre-selection ballot 4-3 to be the Katter Party’s Queensland Senate candidate at the 2022 election, he formed his own political party. The Drew Pavlou Democratic Alliance ran on a pro-human rights, anti-CCP platform that argued Australia should treat China as a pariah state.

While campaigning in Eastwood, a Sydney suburb with one of the highest concentrations of Chinese-Australians in Australia, he held up a sign saying “Xi Jinping, f— your mother” in Mandarin. An angry group surrounded Pavlou and one man tried to grab the sign. Police charged him with offensive behaviour in public and refusing to comply with a police direction to move on – offences that could have led to more than three months in jail. (The charges were later dropped.)

During that campaign, Pavlou also targeted Liberal politician Gladys Liu, the first Chinese-born MP in federal parliament. Among his stunts: posing beside Liu in a khaki Cultural Revolution uniform and parking a billboard outside her office saying “Flush the Liu”. Another claimed she was the preferred candidate of Chinese President Xi Jinping. On social media he promoted the idea she was a Chinese spy. Liberal Senator James Paterson, one of the leading China hawks in parliament, is an ally of Pavlou: “He genuinely sees China as the biggest human rights issue of our age and I agree with him.” But Paterson believes Pavlou’s attacks on Liu were “over the top” and constituted “an unnecessarily personal attack on someone who had been a trailblazer for the Chinese-Australian community”.

Drew Pavlou: “The hypocrisy really stuck with me. I thought I’d just do one protest.” Credit: Attila Csaszar

Erin Wen Ai Chew, of the Asian Australian Alliance, says Pavlou unfairly went after Liu because of her Chinese background. “A lot of things he has done can encourage racism and promote the notion that people of Chinese background are disloyal unless we stand by his side.” Pavlou says he hammered Liu because she failed to disclose her membership of Chinese government-linked associations before she entered politics. “I guess we maybe went too far with the tone we used,” he reflects now. “We were young people fired up for a campaign and we didn’t necessarily have the best advice. But I don’t think it’s racist to attack Gladys Liu for her connections with the CCP. It’s not like I was out there attacking every single politician with Chinese ethnicity. I work hand-in-glove with members of the Chinese dissident community.”

Vicky Xu swats away the notion Pavlou is racist, saying he has formed deep connections with exiled Uyghurs, Tibetans and Hong Kongers and defers to their expertise. “Whenever I point out that it’s not your place to say something, he will listen and apologise,” she says. “Why can’t a white guy talk about how oppressive the Chinese Communist Party is?”

Tibetan rights activist Kyinzom Dhongdue argues that Pavlou’s provocations serve a bigger purpose. “In my activist life I’ve organised rallies, I’ve done things the traditional way. It doesn’t generate news. It doesn’t have enough conflict. Drew is a gifted campaigner who knows what works for the media.”

Still, while Pavlou attracted more headlines during the campaign than most other candidates, his run for office was an electoral flop. The Queensland Senate ticket he led attracted a meagre 4555 votes, among the lowest of any party on that state’s ballot.

Undeterred, Pavlou was back in the headlines a few weeks later when he was ejected from the 2022 Wimbledon tennis men’s singles final in which Nick Kyrgios played Novak Djokovic. He disrupted the event to highlight the case of Peng Shuai, a retired professional women’s tennis player from China who has largely disappeared from view after accusing a former high-ranking member of the country’s ruling Communist Party of sexual assault.

It wasn’t his only action in Britain. He also protested outside the Chinese embassy, holding the Tibetan and Taiwanese flags. London police arrested him after the embassy reported a bomb threat sent under his name. The email allegedly said: “This is Drew Pavlou, you have until 12pm to stop the Uyghur genocide or I blow up the embassy with a bomb. Regards, Drew.”

Drew Pavlou meeting with the Dalai Lama.Credit: @drewpavlou/Instagram

He was handcuffed, detained in a cell and allegedly told he would be unable to contact anyone while the police continued their investigation. The first interview took place at 4am, he says. “I thought, these motherf—ers got me good. I fell into a deep pit of despair,” he says. “No one knew where I was. I was held incommunicado for 23 hours.” He was eventually released without charge but felt a cloud still hung over his head.

In November that year, and back in Australia, Pavlou visited Parliament House in Canberra to meet with Labor MP Peter Khalil, the chair of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security, and James Paterson, the former committee chair. He wanted them to help convince UK police to clear his name. Pavlou had no plans to stage any protests, but while he was drinking an orange juice Australian Federal Police officers told him he had to leave the building. Documents released under freedom of information showed police had identified Pavlou as “an active issue-motivated individual” – a vague descriptor that could be applied to hundreds of lobbyists and activists who regularly pass through Parliament House every sitting week.

Pavlou’s ejection drew instant condemnation from politicians across the political spectrum, who said it was a disturbing precedent for a constituent to be blocked from meeting an elected representative when they had done nothing wrong. The next day police allowed Pavlou back in the building and he celebrated with “victory scones” at the cafe. In December, the AFP issued an apology, delivered to Pavlou at his home in Brisbane. In February, the London Police told media the activist had been fully cleared of wrongdoing. Charges against him in NSW were also dropped; in May, NSW Police announced they were investigating whether an officer fabricated quotes attributed to Pavlou in a brief of evidence in which he supposedly said migrants do not try to fit into Australian culture.

An apology from the AFP. An admission from London Police that he is not a terrorist. Those 65,600 Twitter followers. A meeting with the Dalai Lama, who advised him to have compassion for all human beings, even those he is inclined to hate. In many ways, Pavlou seems to be on a roll. But when we speak for our final interview he confesses he feels like a man who has lost his mojo. He is back studying politics and philosophy at the University of Queensland but misses the high-octane world of protesting and political campaigning. While he was relieved to be cleared by London Police, he says he is still recovering from the experience. “I’m not as vocal, I’m not doing as risky protests any more and that part sucks. I want to go back to doing big grand protests, but it’s difficult because it has caused so much pain for my family, for my girlfriend. It really f—ed me up pretty badly.”

Pavlou says he has been reading a biography of Mao Zedong that chronicles the “long march”, the Red Army’s massive retreat across China to evade nationalist forces. Of the estimated 100,000 soldiers who started the march, fewer than 10,000 are said to have survived. Mao is the last person Pavlou would expect to identify with, but on this point he does. “I feel like going on a bit of a long march,” Pavlou reflects. “Obviously my political party didn’t go anywhere at the election and I don’t think I’ve got the money to keep it going. At the moment, it seems like my ideas are kind of not in vogue. You don’t really see the Australian government talking much about the Uyghurs or Tibetans. It doesn’t really seem to be a top priority for many people.” If Pavlou had his way, the Albanese government would be sanctioning CCP officials and leading a sporting, cultural and economic boycott of China. Instead, he says, the government is trying to repair relations with Beijing and allow Australian goods to again flow freely into the country.

“It’s difficult because it has caused so much pain … It really f—ed me up pretty badly.”

The important thing to remember about Mao’s long march, Pavlou says, is that it laid the foundation for Mao’s eventual rise to power. Sometimes you have to stage a strategic retreat in order to triumph.

Just weeks after Vladimir Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine, Pavlou made a spontaneous trip with some buddies to the Poland-Ukraine border to help deliver humanitarian aid. His social media feed is increasingly focused on Ukraine and documenting the activities of ultra-nationalist Putin supporters in Australia. “This is our generation’s Spanish Civil War,” he says of the conflict. “If Ukraine falls, Taiwan will fall.”

As much as they love him, his parents are ready for him to move out, get a decent job and start supporting himself. Mentors like Tibetan rights activist Kyinzom Dhongdue are urging him to study international law so he can become a human rights lawyer. “I always tell him how much hope I have for him, but he needs to plan properly what he wants to do with his life.” Even though he frustrates her, Vicky Xu hopes her friend keeps at it. “He can come across as arrogant or annoying but deep down he has a good heart. I’m grateful Drew Pavlou exists.”

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article