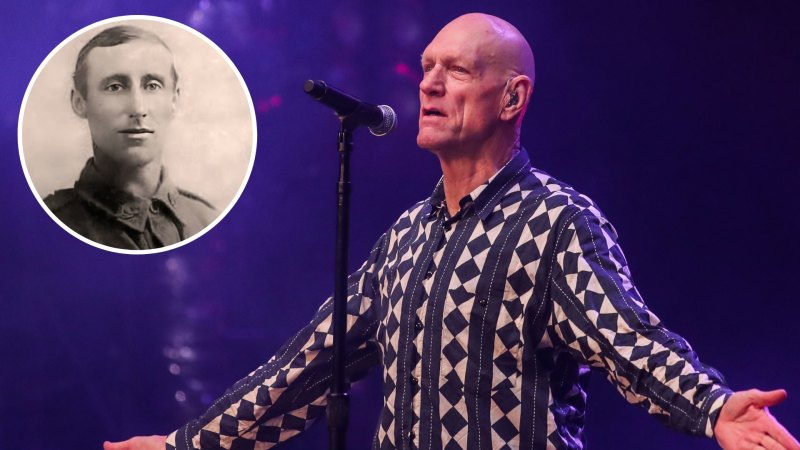

By Peter FitzSimons

Tom Vernon Garrett, grandfather of Australian rocker Peter Garret, was one of many Australian prisoners of war who went down with the Montevideo Maru.

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

It is the wee hours of July 1, 1942. In the tropical waters off Cape Bojeador in the Philippines, Lieutenant Commander “Bull” Wright, the captain of the American submarine USS Sturgeon, is woken from a half-sleep familiar to all submarine commanders – always half-alert – by a sudden change in the sub’s course, and a surge of her engines. There are two likely possibilities. Either the Sturgeon has found a Japanese target, or it is one! After a ringing knock on the metal door a few seconds later, his executive officer tells him – praise the Lord and pass the torpedoes – it is the former. The Sturgeon’s radar has picked up the large pings of a big ship speeding from the Japanese-controlled Philippines north-east, into the South China Sea, and has began the hunt. The operational orders for this American submarine are clear: attack all Japanese targets they come across, the bigger the better.

Unbeknown to Commander Wright, while this target is indeed Japanese, the 7267-ton Montevideo Maru is bearing unusual cargo. Well below decks are 1060 manacled prisoners, most of them survivors of the Japanese invasion of Rabaul. Of these, some 980 are Australians: soldiers, civilians and missionaries. These are the very prisoners whose letters home had been dropped on Seven Mile Airfield, just north of Port Moresby four months earlier by the Japanese, bringing enormous relief in Australia from Palm Beach to Perth, from Darwin to the Derwent River that they were still alive!

There are also thirty-six Norwegian sailors on board, previously rescued from the cargo ship Herstein which the Japanese bombed. Now they all sleep as their prison ship ploughs on through the moonlit sea . . . completely unaware the Sturgeon is beginning to close.

In the submarine, tension is high. There is little noise in the conning tower as officers and men systematically go about the work they have been trained to do. Apart from a few muttered orders, the major sound is the strained hum of the sub’s engines on full power.

Wright and the exec select a salvo of four torpedoes for the attack, two aimed directly at the ship and one on either side, in case the ship sights the inbound torpedoes and alters course. Twenty minutes after spotting the ship the Sturgeon has closed the gap. Now they can fire the spread of torpedoes at the Montevideo Maru and dispatch it to where, in Bull Wright’s view, all Japanese shipping belongs: the bottom of the ocean.

The final settings are applied and Commander Wright gives the order in his authoritative, calm voice: “Fire one”.

The order is repeated by the exec— “Fire one” — and the whole submarine shudders and shimmies as the first torpedo bursts forth. Bull Wright and the exec click their stopwatches simultaneously and continue.

“Fire two . . . ” “Fire two . . .”

“Fire three . . .” “Fire three . . . ”

“Fire four . . .” “Fire four . . .”

It is exactly 02:25 hours as the Sturgeon crew feel the last torpedo discharge, firing out at a range of just under 4000 yards from the Montevideo Maru. Both the submarine commander and his number two look at their stopwatches. The “time to run” is critical if they are to know whether the torpedo has exploded prematurely or has run past the target. The second hands of the watches slowly click by as the seconds to run are counted down aloud by the exec. There is a hollowness in everyone’s stomach in the conning tower as the impact time of the first torpedo passes, with no sound. Nothing!

Concerned, Bull Wright orders, “Periscope up,” and brings it to bear just in time to observe an extraordinary thing.

First, he sees the Montevideo Maru suddenly alter course and now, almost instantaneously, there are two large explosions, as two of the torpedoes penetrate the bowels of the ship and erupt. Almost instantly the ship begins to list to starboard as wild panic breaks out on board.

For the manacled prisoners below there is no chance, and only 18 of the Japanese crew manage to launch a couple of lifeboats. At 02:40 hours, stern first, the Montevideo Maru sinks to the bottom of the ocean, taking all bar the Japanese with it.

Bull Wright doesn’t wait to watch the ship sink. He orders the Sturgeon to a depth of 200 feet and to “rig for silent running”, just in case there are any enemy combatants nearby, and plots a course to establish maximum distance from any Japanese warships that might be rushing to its aid. As the submarine glides into the deep, the final noises of the ship breaking apart can be heard. Like a spring unwinding, the tension of the pursuit and attack drift rapidly from Bull Wright’s mind as he applies his thoughts to the safety of his submarine and his men. In Wright’s and his crews’ minds is the grim satisfaction – they have done their jobs well.

Among the Australians who lost their lives that day was Tom Vernon Garrett, who had served with the 6th Australian Light Horse Regiment in World War I before becoming a planter in the New Guinea plantations, where he had been captured by the Japanese.

Tom Vernon Garrett served with the 6th Australian Light Horse Regiment in World War I before becoming a planter in the New Guinea plantations, where he was captured by the Japanese. His grandson is Peter Garrett, best known as the frontman for rock band Midnight Oil.

The fact that he was the grandfather of Midnight Oil’s lead singer Peter Garrett prompted the rocker to write about him in the Oils’ song, In The Valley, beginning,

My grandfather went down with the MonteVideo

The rising sun sent him floating to his rest

And his wife fled south to Sydney seeking out safe harbour

A North Shore matron she became with some paying guests

As a cabinet minister in 2009, Garrett became the patron of the Montevideo Maru Memorial Committee, an organisation which has long agitated for a proper search for the wreck of the ship to be done.

So, on April 22, this year, Garrett and other relatives were overjoyed at the news researchers and defence personnel had finally located the ship.

“I felt amazement, relief, and gratitude, that finally so many peoples’ resting place is now known after a lifetime of uncertainty,” Garrett told this masthead.

The American submarine USS Sturgeon fired four torpedoes, two of which are believed to have struck the Montevideo Maru.

The expedition that found the wreck is under the umbrella of Sydney’s Silentworld – a not-for-profit organisation devoted to maritime archaeology – and the Dutch deep-sea survey company, Fugro. They were supported by the Department of Defence, while their driving force and financial contributor was the chair of Telstra, John Mullen, who is also chair of the Silentworld Foundation. (Mullen and Silentworld were also responsible for solving Australia’s other great maritime mystery, the location of the Australian submarine the AE1, which had disappeared off the Duke of York Islands in Papua New Guinea in September 1914, with 35 crew onboard. It was located in December 2017.)

After five years of planning, the Fugro Equator with 37 crew and five professionals from Silentworld set sail from the port of San Fernando in the Philippines on April 6. Their search area had been narrowed down thanks to Harumi Sakaguchi, a Japanese researcher who provided critical information. With the expedition is Commodore Tim Brown, who recently retired from the Royal Australian Navy.

“It was amazing,” he said on Sunday. “The first time we launched the Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) we’d hoped the ship would be exactly where we thought it would be. But there was nothing. So, we knuckled down and said we’d step through each of the search areas one by one in a very disciplined approach.”

The AUV then went back and forth over each designated search area, a process that Brown described as “like mowing the lawn”.

And then, suddenly, on the afternoon of April 18 at 2pm, “on the final search line”, there she was!

Left to right: Tim Brown, Max Uechtritz, at the back with Neale Maude, Roger Turner, John Mullen wearing a cap on the right and Andrea Williams.

“If it hadn’t painted up then, we would not have found it for a few more weeks as the subsequent search areas were to the south followed by a counter-clockwise snail-like pattern around from the centre. Of course, our days on task are limited and if further bad weather had caused delays we may never have got back to her. So providence played its hand.”

It was a moment he will never forget.

“So we were first taken by surprise when she [showed up], sitting so peacefully 4000-plus metres below. From the imagery, it looks like one torpedo hit forward and one aft. There was immediate elation at the find, then sombre silence. All of us realised that so many souls lay deep below our vessel. It was an emotional experience.”

Former ABC journalist Max Uechtritz who is filming a documentary for Silentworld, agrees.

“I have been in the middle of many world events in my career,” he said, “but nothing as emotional as this. Yes, there was jubilation, but immediately we all thought of the families of the lost men, who had known generational trauma, who had been shunned and ignored, but who had never stopped fighting for the final resting place of their loved ones to be found. And now we had found it. We were profoundly moved.”

Over eight decades later, those lost on the Montevideo Maru had not been forgotten, and have now been found by an Australia which still mourns them on Anzac Day.

Lest we Forget.

The historical account above is an edited extract from Peter FitzSimons’ book Kokoda.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article