A dead bird is not a pretty sight. I’d steeled myself for the carcasses but I wasn’t prepared for them dying right in front of my eyes writes JACKIE BIRD

A dead bird is not a pretty sight, so I’d steeled myself for the carcasses I’d been told were littering the coastline. But what I hadn’t prepared myself for were the dying. The moribund. The pathetic shuffle of the once wild things now strangely docile and oblivious to my presence, wandering the coastal paths looking for places to die.

A few feet away from me a young kittiwake took a few stuttering steps. It stopped occasionally to throw back its head, but then it fell over in the grass, one wing flailing and outstretched as it gathered the strength to continue its pitiful journey.

My guide, Ciaran Hatsell, the head ranger at St Abb’s Head national nature reserve, shook his head. ‘It’ll be dead in a few hours.’

I could tell Ciaran, a passionate nature lover who revels in being outdoors, was finding it difficult. His job with the National Trust for Scotland is to care for and protect the vast array of seabirds that seek out this spectacularly gorgeous piece of Berwickshire coastline.

Its rugged cliffs form a giant seabird city for the tens of thousands of birds who traverse the globe and come here to breed.

Jackie Bird, President of the National Trust for Scotland, steeled herself for the carcasses she’d been told were littering the coastline

What I hadn’t prepared myself for were the dying. The moribund. The pathetic shuffle of the once wild things now strangely docile and oblivious to my presence, wandering the coastal paths looking for places to die

In return for their board and lodgings they provide a constant performance of dare-devil aerobatics accompanied by a screeching cacophony of calls.

However, this summer avian flu has caused devastation among some of the species and left Ciaran feeling helpless.

Kittiwakes, small gulls who get their names from their distinctive call, have been particularly badly hit. The birds’ features are smaller and less sharp than their thuggish chip-stealing cousins, so they’re nicknamed ‘the kind birds’. As we watch this youngster taking its last steps, the anthropomorphising only makes me sadder.

‘Death is part of life on a seabird colony, or on a seal colony, or wherever you work with wildlife,’ Ciaran says, ‘but to see it on this scale and to see it affecting chicks which are pretty helpless is horrendous.’

If you think you’ve had a rotten summer so far – our seabirds have had it worse. Last year saw the UK’s worst ever outbreak of avian flu, and a few weeks ago, this time a bit later in the breeding season, it came back.

‘We’re better set up to deal with this second wave,’ says Ciaran, ‘but nothing prepares you for it. It’s still a shock to see birds you’re passionate about, that you love, you monitor, you see every day, dying like this.’

We leave our ailing fledgling in peace.

I had no idea avian flu had such heart-rending neurological effects. The strain of the virus, H5N1, also causes respiratory symptoms and other signs on the birds’ bodies, but the indignity of these once majestic wild birds wandering lost and confused seemed like death’s unnecessary insult.

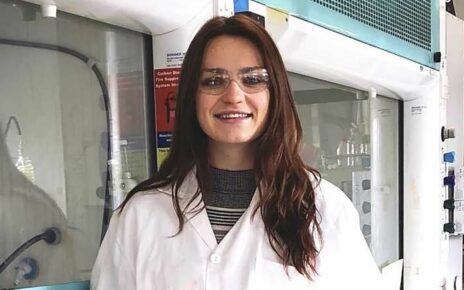

Jackie Bird with Head Ranger, Ciaran Hatsell, at St Abbs National Nature Reserve.Pictures supplied for feature about avian flu

Dead and dying birds at St Abbs National Nature Reserve

And to think the team at St Abbs thought that this time they’d been spared. After last year’s catastrophic outbreak of avian flu, the early summer months began without event. ‘At the beginning of June we thought we’d got away with it,’ Ciaran explains. ‘However, in early July the numbers ramped up.’

He takes me to the cliff edge beside the famous St Abb’s Head lighthouse. Beneath the rocky promontory is a pile of dead birds with a handful of carcasses floating in the bay.

On the slopes I spy a couple of people with serious looking binoculars who’ve settled into grassy crevices, monitoring the scene. They look official, and they are.

Scotland is world famous for its scenery and its wildlife. The scale of last year’s avian carnage with the deaths of hundreds of thousands of birds came as a shock to the many conservation agencies whose role it is to protect our natural environment.

Gannets were particularly badly hit, their reputation as gregarious party birds who love to live and feed together proved, literally, to be the death of them. That sociability led to a rapid spread and in some colonies in Scotland, 90 per cent of chicks were lost.

Great skuas, the so-called pirates of the seas because of their habit of swooping and stealing food from other birds, also suffered catastrophically. In colonies on Shetland, 80 per cent were wiped out.

Many other seabird species were affected as were swans and ducks, and raptors including falcons and eagles.

It might come as a surprise to those of you who’ve never worked in a bureaucratic environment that the various bodies who champion our natural world can sometimes display the cooperation and camaraderie of ferrets in a sack. But the crisis of last year led to an unprecedented coming together of government, conservation groups, local authorities and scientists in an urgently convened national task force.

This year, in the face of another looming catastrophe which so far thankfully seems to be only affecting the east coast of Britain, everyone is working together to share expertise and research.

READ MORE: Third wave of deadly avian flu puts many of Scotland’s favourite seabirds ‘on the brink of extinction’

There is no cure, no Covid-style vaccine, but what can be done includes tracking, monitoring and continuing study. The advice to you and me is to stay away from ailing or dead birds, report any carcasses and keep dogs on a leash.

It seems a pretty insignificant response to a wildlife disaster – but before my tale of woe completely ruins your day, there is hope. Ciaran explains: ‘Earlier this year we found that nature had given us a visual clue to spot the birds who had avian flu but survived. Some gannets’ eye colour had gone from pale blue to black. Can you imagine if that had happened to humans during Covid? People who’d had it walking around with jet black eyes?’

That discovery was made not so far away by scientists on the Bass Rock, the home of the largest Northern gannet colony in the world. They found the eyes of the majority of birds with antibodies to avian flu had gone from their usual Cillian Murphy vivid blue to an intense black, offering a non-invasive diagnostic tool. ‘It’s been uplifting,’ Ciaran adds, ‘because the only way out of this is that the birds develop immunity and that this immunity can spread.’

I hope he’s right, because the source of the horrors of avian flu come not from nature’s tooth and claw, but from human behaviour. Avian flu has been around for more than a century but the recent devastating mutation of the virus originated in intensive poultry farming. It seems that pile-them-high-sell-them-cheap food comes at a cost. Who knew?

I’m not fond of people who preach at me. I bridle at the activists who tell me how to live my life to ‘save the planet’ – yet here I am hypocritically doing the same thing. I’d argue that it’s difficult to sit on the fence when we’re causing such suffering to our fellow creatures. And although we may be powerless in the face of avian flu and placing all our chips on nature’s nascent immunity – what about the rest of the kicking we’re currently giving our seabirds?

From industrial scale fishing that robs them of their diet to offshore wind farms. Yes, you read that correctly. As I sit on the cliffs of St Abbs Head basking in the raw beauty of the sea, I’m also looking at the proposed site of a huge offshore wind-farm that will potentially disrupt vital seabird feeding areas.

You could argue it’s a good idea for the green energy lobby, but on this occasion it’s in the wrong place.

On this sunny day at St Abbs the bird population is free-flying and uplifting for visitors, but our marine wildlife is in peril and needs all the help it can get. Thirty years ago there were nearly 20,000 kittiwakes at St Abb’s Head now there are under 5,000, and that’s without avian flu’s deadly input.

But if you come here, and I hope you do, you won’t see killing fields. Any dead birds are being quickly cleared and the walks and the views are still magnificent. But that natural beauty is a fragile thing and it’s on our watch.

On the way home from St Abbs, Ciaran sends me a text with a picture of our young struggling kittiwake. It’s dead.

- A special episode of Jackie Bird’s Love Scotland podcast series about avian flu is out now.

Source: Read Full Article