JACKSON, Miss. — The burden of Jackson’s latest water crisis has fallen on the shoulders of this city’s youngest and most vulnerable residents.

The capital city is without a reliable water supply because of flooding, and it’s not clear when residents will be able to expect safe running water.

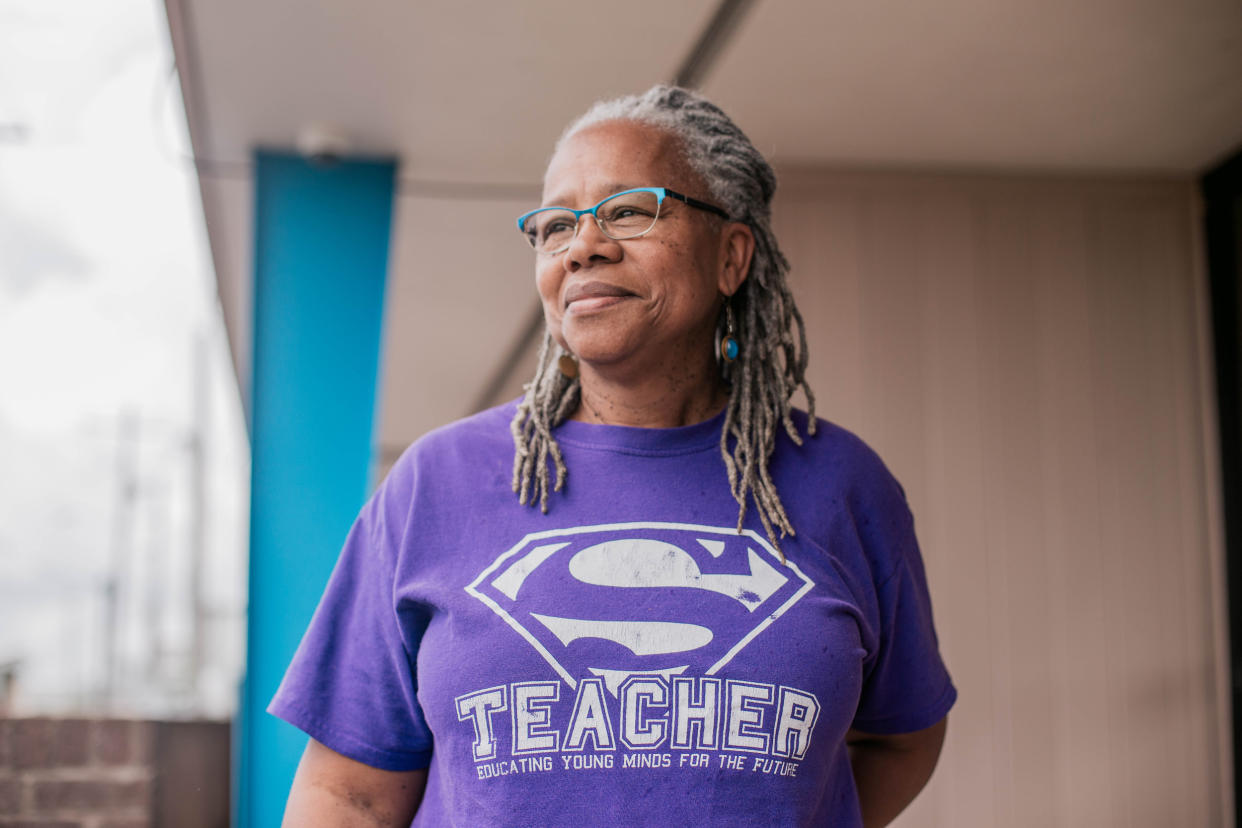

Lorene Terrell, 59, could only shake her head Tuesday at the sight of her 11-year-old granddaughter struggling to carry home bottled water, during a time when she otherwise would have been in a classroom.

Schools in Jackson, Mississippi’s capital and largest city, have shifted to virtual learning in light of the crisis.

“They need to be at school, instead of here with me because they’re just playing,” Terrell said, as her granddaughter and grandson, 5, swapped their schools books for firsthand lessons about failed infrastructure.

Terrell can’t grasp how she pays a monthly water bill only to be plagued by constant disruptions.

“It shouldn’t be like this,” she said.

At Jackson’s only Walmart, Namiah Thomas, scanned the thinning options of bottled water on the shelves.

Much of what remained was flavored or sparkling. Jackson had been under a boiled water notice for a month when Monday’s state of emergency was announced, further straining supplies.

Thomas said she initially lost water pressure in her West Jackson neighborhood Monday, but that the flow has since improved.

The restoration gave her little confidence. She suspected the brown water coming out of her faucets Tuesday morning was contaminated.

“If you fill up your tub and your tub’s white, you’d be able to see the actual color of the water,” she said of the water coming out of the spout. “I wouldn’t touch it.”

Like thousands of residents, Thomas was affected by a 2021 cold snap that left parts of the city without reliable water for weeks. Obtaining clean water to get through daily activities, she said, has grown more costly since.

“It seems like the more crises we have in Jackson with the water, the more the prices go up,” Thomas said.

She managed to get by with her fiancé during the 2021 water shortage, but now she has a 1-year-old and 4-month-old to worry about.

“She’s so little. I just can’t be without,” Thomas said. “It’s essential; everyone needs water.”

The city of 150,000 residents, nearly 83% of them Black, has long been plagued by infrastructure issues that have made clean, reliable water a challenge.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba declared a water system emergency Monday evening because of complications from the Pearl River flooding. He said issues at the O.B. Curtis Water Plant resulted in low or no water pressure for many residents.

Gov. Tate Reeves followed the city’s announcement with his own declaration of a state of emergency Tuesday. And Tuesday night, President Joe Biden approved Mississippi’s emergency declaration request.

Lumumba said residents know this latest emergency is a drop in the bucket, compared to the years of water struggles.

“The city of Jackson, even when we’re not under a boil water notice, even when we’re not contending, at that present moment, with low pressure, we are in a constant state of emergency,” he said Tuesday.

This week’s outage couldn’t have been more ill-timed for Greg Watts, whose wife gave birth to a baby boy last week.

Watts came to Walmart on Tuesday in hopes of finding distilled water to prepare formula for his infant. His family’s South Jackson home, he said, has had poor water pressure for about a week.

There’s not enough pressure to take a shower at home, and the family has been commuting to his mother’s house in a rural area of Hinds County.

“It’s rough,” he said.

Frustration with state and city leadership was evident among Jacksonians in the southern edge of the city, where residents are particularly vulnerable during outages and where some people began losing water last week.

“They should be on every corner with cases of water,” Tim Finch, a resident who works with Operation Good, a violence interruption group in the city, said of local and state officials while waiting on a truckload of bottled water to distribute near a South Jackson neighborhood.

In a community that many feel is neglected, taking a grassroots approach to the latest water system failure, he said, is necessary to survive.

“We’ve got to take care of each other,” Finch said.

“Y’all got the water yet?” one driver called out, before being instructed to return later.

At distribution sites, sometimes only a few minutes stands between people waiting in line and the last free case of bottled water.

After about 30 minutes of loading water into cars in the scorching Mississippi heat, the group was out of supplies again.

Bracey Harris reported from Jackson and David K. Li from New York City.

Source: Read Full Article