David McCulloch’s initial advice to Jason Roberts was the same he gave every prisoner who asked for his help: don’t treat me like a mug – if I find out you have lied to me, you can take your story somewhere else.

The difference with Roberts was that, unlike in the case of nearly all the other inmates the self-styled jailhouse lawyer dealt had with, McCulloch believed Roberts was telling the truth, that he wasn’t there on the night Senior Constable Rodney Miller and Sergeant Gary Silk of Victoria Police were murdered.

According to McCulloch, inside the walls of Barwon Prison, not many shared his belief.

Self-styled jailhouse lawyer David McCulloch, living in exile in London, believes that justice was served with the acquittal of Jason Roberts.Credit:Hollie Adams

“They said, ‘Dave, he is probably leading you up the garden path.’ But there was something about him. Jason’s story was one of only a few of literally hundreds of my then peers whom I believed.”

He also believes that, following last week’s acquittal of Roberts after a retrial, justice has been served.

It was in the common room of the Eucalypt Unit, a section of Barwon Prison set aside for “long termers”, where Roberts began a long and for many years seemingly futile campaign to overturn his conviction for one of the state’s most notorious crimes.

In a corner of the room sat a large table and a bookcase. This is where McCulloch, a Glasgow-born former social worker serving a lengthy stretch for drug trafficking, could be found each day between 10am and 4pm, talking to inmates about their legal woes.

He’d initially set up shop, with the support of prison authorities, to help illiterate prisoners fill out forms and write to their families. Over time, his jailhouse practice extended to giving people advice about how best to appeal their convictions and shave time off their sentences.

McCulloch wasn’t a qualified lawyer and didn’t profess to be. To someone like Roberts, a young man who had already lost an appeal against his conviction and was confronting the reality of spending the next 30 years of his life behind bars, he was a counsel of last resort.

On the day the jury returned its verdict of not guilty, McCulloch was ecstatic. Few inside the Supreme Court had any inkling of his involvement. “My part in this story was ever so small,” he tells The Age. “Without the commitment of his lawyers, his family and [former detective] Ron Iddles, his acquittal could have never happened.”

Jason Roberts walks out of custody for the first time in more than two decades after being acquitted of murdering police officers Gary Silk and Rodney Miller in Melbourne’s south-east in 1998.Credit:Jason South

Roberts and McCulloch became friends shortly after McCulloch arrived at the maximum-security Barwon Prison, north of Geelong, in 2005. They would go running in the morning, work out at the gym and sit at the same table for meals.

Their regular companions included Christopher Hudson, a hulking bikie who murdered a man and shot two other people in a senseless early morning rage in Bourke Street; Matwali Chaouk, jailed for targeting a member of a rival crime family in a drive-by shooting in Altona; and Daniel “Porky” Lovett, an accomplished boxer and sergeant-at-arms of the Melbourne chapter of the Hell’s Angels.

McCulloch was older than the others and had spent enough time in jail to understand its bleak reality. He had previously worked with delinquent youths at the old Turana Boys’ Home. He now served as prison yard mentor, extolling the virtues of staying fit and keeping an active mind.

While at Barwon, he was involved in a joint program with Deakin University aimed at deterring adolescent offending. Last year he related his jail experiences to 85,000 British prisoners through the BBC’s National Prison Radio.

In about 2007, Roberts started to talk to McCulloch about the Silk and Miller murders. At first McCulloch mostly listened, sceptical about what he was being told. The more Roberts confided in him and the more he learned about Bandali Debs, the remorseless career criminal who confessed to murdering Miller, the more he became convinced that, although Roberts was not an innocent man, he was no killer.

Some days they would talk over walks around the prison yard. On other days, McCulloch would sit at his desk in the common room, taking notes of Roberts’ recollections. “It got to a stage where he gained trust in me. I think that is eventually why I got the full story.”

McCulloch says Roberts paid a heavy price – nearly 10 years in solitary confinement – in pursuit of freedom.Credit:Hollie Adams

For McCulloch, the most compelling part of Roberts’ story was his preparedness to reveal to him two locations where guns, duct tape, clothing and Silk’s police diary were hidden after the murders. Roberts said he knew this because, after Debs told him what he’d done that night in Moorabbin, he helped him bury the evidence. He also confessed to McCulloch that he carried out 10 armed robberies with Debs in 1998, in the lead-up to the murders.

Roberts said Debs had promised to come clean and support his version of events once his own avenues for appeal were exhausted. Armed with this information, McCulloch organised a delegation of influential prisoners to confront Debs, who was also in the Eucalypt Unit. Debs pledged to them, as he had to Roberts, that he would back up Roberts and tell police the younger man had no involvement in the murders.

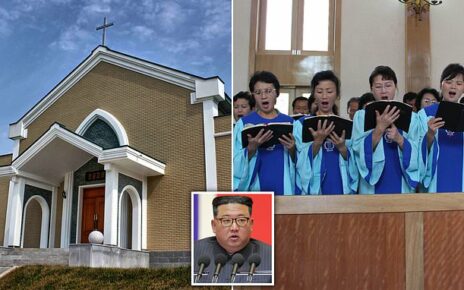

Sergeant Gary Silk and Senior Constable Rodney Miller.

By the time Debs was transferred out of Barwon to the Goulburn “supermax” prison to stand trial over another murder, he had done nothing to uphold this promise. When he appeared as a prosecution witness at Roberts’ retrial, it became clear he never intended to.

McCulloch says he urged Roberts to tell his lawyers, and eventually police, what he had told him. “To have a chance, he had to come clean about the previous lies and the cover-up,” McCulloch says. “I said look, there is only one way around this, but you are going to have to be careful.”

McCulloch advised him on how to word his statement. He also explained to Roberts that once he started talking to police, he would be shifted into solitary confinement, away from the general population, and locked down 23 hours a day.

Roberts ended up spending nearly 10 years in isolation. It was, McCulloch says, a high price to pay.

Retired homicide detective Ron Iddles was called as a witness for the defence in the retrial of Jason Roberts.Credit:Penny Stephens

Roberts made two approaches to police. The first, through barrister Sean Grant, was passed all the way up police command to then chief commissioner Simon Overland, but no action was taken. In late 2012, he contacted Marita Altman, a lawyer who represented him during his first trial in 2002. Through Altman, word reached Ron Iddles, a homicide detective nearing the end of his career, that Roberts wanted to set the record straight.

Iddles agreed to listen to what Roberts had to say.

Like McCulloch, Iddles treated the revelations about buried evidence as significant. At one site, a boat ramp in the Bass Coast town of Tooradin, only scraps of clothes were recovered following an extensive search of the area. At the second location, Toorongo Falls in Gippsland, neither the guns nor the diary was found but a roll of duct tape was.

The items had little evidentiary value but for Iddles they corroborated Roberts’ version of events. Through the course of his investigation Iddles started to entertain an idea that, within Victoria Police, was taboo: the convicted cop killer might just be telling the truth.

The irony for McCulloch is that, perhaps as a consequence of the assistance he gave Roberts, he is marooned in London and, at age 73, unable to return to the country where he spent nearly all his adult life and where his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren live.

As a non-citizen with a serious criminal record, McCulloch was always vulnerable to deportation. In 2015, then immigration minister Scott Morrison ruled that his visa should be revoked upon his release from Barwon. McCulloch fought this decision and by 2017 had convinced Morrison’s successor Peter Dutton – with the help of testimony from senior corrections administrators – that he was sufficiently reformed to remain in Australia.

In February 2019, Victoria Police provided a further, secret report to Dutton which catalogued McCulloch’s criminal past and raised speculative allegations about his involvement in unsolved crimes. It also characterised his jailhouse lawyering as a scam designed to rip off gullible prisoners. McCulloch says nearly all of his legal work was done pro bono.

The police report contained no evidence of criminal activity by McCulloch since his release from jail but served its purpose. Dutton reversed his decision and in early 2020, just before the pandemic grounded international travel, McCulloch boarded a plane to Britain.

The most telling claim against McCulloch in the police report was that he supported a push, at the tail end of Melbourne’s gangland wars, for a royal commission into police corruption. History shows he had good cause.

Disgraced former drug squad detective Wayne Strawhorn provided evidence to the Lawyer X royal commission.Credit:Jason South

The drug trafficking charges which resulted in McCulloch serving 13 years at Barwon were based on a sting operation involving two police detectives since jailed for drug dealing: Wayne Strawhorn and Malcolm Rosenes. Rosenes alleges in an affidavit that evidence against McCulloch was planted in his apartment. McCulloch admits to earlier drug offending for which he also served jail time but insists that in 2005 he was stitched up by crooked cops.

A special investigator appointed after the Lawyer X royal commission to determine whether police should face criminal charges is examining McCulloch’s drug conviction and the circumstances of his deportation.

In his only public comments since being released from jail, Roberts expressed relief at being reunited with his family. The jailhouse lawyer who helped him is chasing the same thing.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article