I watched concentration camp prisoners burn an SS guard alive: Speaking days before his death at the age of 103, the last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor Ben Ferencz revealed why he believed vengeance was NEVER the answer

Nearly 80 years later, Ben Ferencz could still recall watching in horror as concentration-camp prisoners, days after their liberation, captured an SS guard and burned him alive in one of the Nazis’ own ovens.

‘Not all of the inmates were helpless,’ he told me. ‘They caught one of the guards and they beat him with their fists. Somebody brought from the crematorium one of the trays they used to shovel people into the furnace. They tied him to it and put him in the oven, just enough to warm him up.

‘Then they pulled him out again, beat him up again, put him in again, burned him up again — about two or three times until he was well-cooked.’

Ferencz added: ‘It was, of course, a horrible experience to watch this. But I didn’t dare try to stop it because they would have turned on me.’

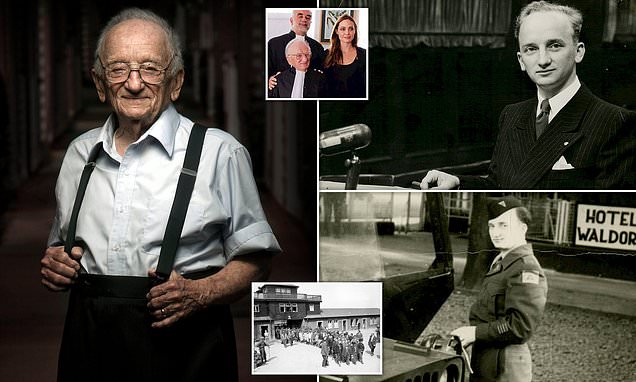

Few had such a vivid perspective on man’s inhumanity to man than Ben Ferencz, last surviving prosecutor from the Nuremberg war crimes trials, who died on Friday aged 103. His remarkable and at times harrowing life taught him lessons that he went to great lengths to ensure were not lost to history.

The last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor, Ben Ferencz, died on Friday aged 103

Benjamin Ferencz at the podium at the Einsatzgruppen Trial, Nuremburg, in 1947

Although he passed away peacefully in his sleep at a care home in Delray Beach, Florida, he remained extraordinarily active right up until his death. After he got to 100, he boasted he could still do 100 press-ups every morning.

‘Today the world lost a leader in the quest for justice for victims of genocide and related crimes,’ said the U.S. Holocaust Museum.

Ferencz had been awarded the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal in January but was unable to attend the ceremony due to declining health — although even in his last years he was still fighting for justice by ensuring that war criminals were tried in court.

The horrific fate of the SS guard — Ferencz could not remember which camp it was, as he visited many as a Holocaust investigator for the U.S. Army — taught him a ‘very important’ lesson, he told me in 2021 in one of his final interviews. ‘I learned that vengeance is not a way to settle any of our disputes. Because if you turn loose the vengeance, everybody is going to kill everybody.’

It was the same message — ‘Vengeance is not our goal’— that he delivered in his memorable opening statement at the Nuremberg trials in 1947. There, as a 27-year-old U.S. Army sergeant who, at 5ft 2in, was so small he needed to stand on a pile of books to reach the lectern, Ferencz was chief prosecutor of the commanders of the notorious Einsatzgruppen.

These were the SS death squads that rounded up and murdered at least two million men, women and children including Jews, Gypsies and other ‘undesirables’ as the Nazis advanced through Europe. Many of the victims were shot so they fell into mass graves or were herded into vans to be gassed.

It was described by the military tribunal as ‘the biggest murder trial in history’. The 22 defendants were ‘not charged with sitting in an office hundreds and thousands of miles away from the slaughter . . . these men were in the field, actively superintending, controlling, directing and taking an active part in the bloody harvest.’

As a Jew whose family had fled anti-Semitism in Transylvania when Ferencz was only a few months old, he and his relatives would themselves have been exterminated without compunction by the men he was prosecuting.

Benjamin Ferencz pictured next to the Hotel Waldorf during World War II

And yet, talking to Ferencz, I — like many who met this incredible man — was taken aback by his feelings about the Nazis so many years on.

‘The main lesson I learned about the Holocaust is that war will make mass murderers out of otherwise decent people,’ he said.

His oft-repeated mantra was ‘law not war’, and he believed passionately that mankind should try to sort out its differences in the courtroom rather than on the battlefield.

Many might see this as painfully idealistic, but then they hadn’t seen the horrors witnessed by Ferencz. He was raised in poverty in New York — his one-eyed father was a cobbler — and his family were forced to live in the crime-ridden Hell’s Kitchen neighbourhood, where Ferencz developed a lifelong commitment to upholding the rule of law.

He won a scholarship to Harvard Law School and sat his legal exams. When the U.S. joined World War II, Ferencz was desperate to fight but too small to be a bomber pilot, as his feet wouldn’t reach the pedals.

Other arms of the military also rejected him but he was eventually allowed to join an anti-aircraft artillery unit. He saw action in Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge.

As the Allies discovered the true extent of Nazi atrocities, Ferencz was transferred to a war crimes investigation unit.

He helped liberate the Buchenwald, Mauthausen and Flossenburg concentration camps. Ferencz, armed and driving a Jeep, arrived at some camps even before the medical teams, reaching the front entrance of one camp as the SS guards fled out the back, the crematorium ovens still burning.

Pictured: Ben Ferencz at the closing of Lubunga Trial with Angelina Jolie in 2009

‘My most vivid memories are the piles of bodies on the ground that might have been dead or alive, the stacks of skeletal bodies piled up like firewood in front of the crematoria, the inmates behaving like rats in garbage, crawling for a bite to eat,’ he said.

‘And the crematoria going full blast. The stench of the burning bodies . . . I can’t talk about it much either because it flashes back into my mind.’

Decades later, small human stories from that terrible time could still affect him. His voice caught as he told me about a boy whose father had died of starvation just as Ferencz entered a camp. The boy told him how his father had routinely smuggled him a piece of his measly bread ration, hiding it under his arm at night so the other inmates wouldn’t steal it.

Honourably discharged from the Army in December 1945, Ferencz returned to New York and married his wife Gertrude three months later. They went on to have four children and she died aged 99 in 2019.

A chance encounter on a street corner with a former Harvard classmate who was connected to efforts to bring the Nazi leaders to justice sent him back to Germany in 1947.

In Berlin, he was given a team of investigators who were charged with delving through Third Reich offices and archives.

The Nazis were sometimes scrupulous about documenting their vilest work and Ferencz’s team found an almost complete set of secret reports describing the monstrous activities — including precise numbers of victims killed — of the Einsatzgruppen.

He used this bombshell evidence to persuade his superiors they needed a new Nuremberg trial for the Einsatzgruppen commanders. They initially refused, citing staffing and budgetary pressures, but Ferencz persevered. The evidence was all on paper, he pointed out.

Pictured: Inmates of the German concentration camp Buchenwald near Weimar, Germany, march to receive treatment at an American hospital after the camp is liberated

Despite having never prosecuted a case before, he was made chief prosecutor. Although Ferencz had identified 3,000 Nazis who deserved to be tried, there was room in the court only for 22.

Not interested in pursuing the mindless thugs who simply followed orders, Ferencz selected the most educated and ‘civilised’ Nazis, keen to make a point about the brutalising nature of war.

Of the 14 sentenced to death, only four were hanged. Ferencz visited one of the commanding officers, Otto Ohlendorf, a former academic, in his cell before he was executed. Ohlendorf, who admitted killing 90,000 people, had instructed his troops to save ammunition if a mother was holding a baby to her breast by shooting the baby: the bullet would pass through both of them.

‘He was a father of five children and happily married,’ Ferencz told me. ‘And I said in German: ‘Can I do something for you?’ I had in mind he was going to say: ‘Tell my wife I love her, tell my children I’m sorry.’ Not a word. He said: ‘You’ll see I was right.’ ‘

That said, Ferencz believed that most of the Nazis were not simply ‘evil’, a simplistic assumption trotted out in decades of Hollywood films. He says they genuinely believed Hitler’s insistence that Russia would attack Germany, reasoning that killing anyone — including the Jews — who might help the Soviets was a justified act of self-defence.

What he’d seen in the camps and heard at Nuremberg changed Ferencz’s life. Working as a lawyer back in New York, he led efforts to return property to Holocaust survivors and ensure Germany agreed to permanently look after its Jewish cemeteries. In 1970, he stopped practising law and devoted himself to promoting peace.

His ideas for an international legal body like the Nuremberg tribunals became the basis for the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

When, in 2012, the court delivered its first verdict — convicting Congo warlord Thomas Lubanga Dyilo of using child soldiers — it invited Ferencz, then 92, to make the closing remarks.

Describing himself jovially as ‘a little guy dealing with war criminals’, Ferencz said he still tended to weep when he recalled what he saw in the camps — though he had little time for sentimentality.

His son Don, an academic living in Wales, told me in 2021 that he believed his father’s commitment to the cause was ‘what keeps him going, keeps him young’.

Don said yesterday: ‘As children growing up, my dad admonished us, ‘Don’t leave a place the way you found it; leave it the way you would like to have found it.’ I think that’s a lesson that all of humankind ought to take to heart as far as our dear old planet goes.’

Ferencz was ‘deluged’ with cards and emails on his 100th birthday. Unlike British centenarians who receive a card from the monarch, the U.S. president doesn’t offer the same honour. ‘I’d rather skip that one,’ said Ferencz archly, in reference to then White House incumbent Donald Trump.

He was far more touched to receive one out of the blue from a German woman who is the great-niece of one of the men he prosecuted at Nuremberg. She wanted him to know she had appreciated what he’d done, showing the Nazis there was a ‘better way — one of justice, tolerance and truth’, as she put it.

With Ben Ferencz’s death, the world has lost a vital witness to the most barbaric period in humanity’s recent past. The lessons he espoused, however, will hopefully resonate long after him.

Source: Read Full Article